Continuing . . .

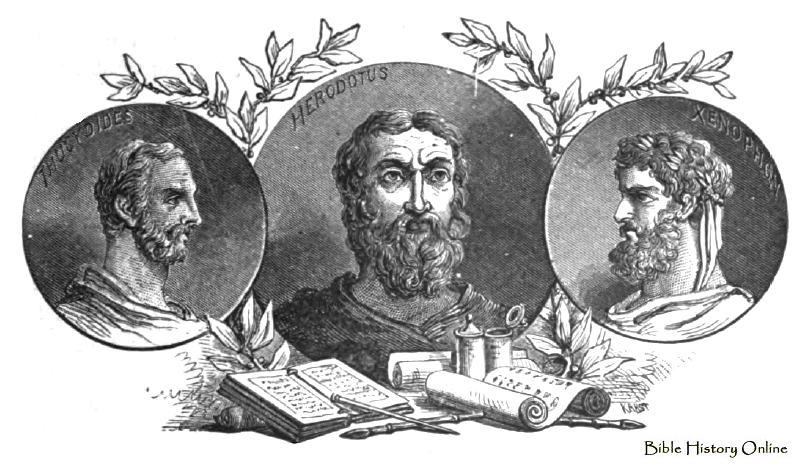

The first century B.C.E. (Celtic) Roman historian Pompeius Trogus wrote Historicae Philippicae (Philippic History), of which an epitome survives. The relevant section:

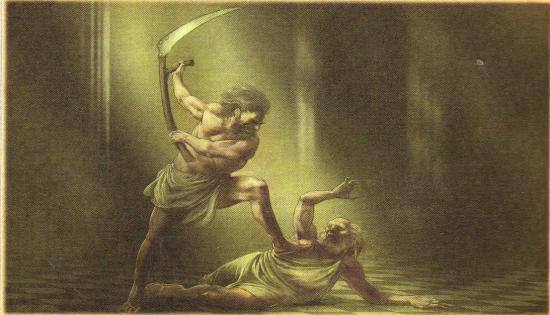

But a prosperous family of ten sons made Israhel more famous than any of his ancestors. Having divided, his kingdom, in consequence, into ten governments, he committed them to his sons, and called the whole people Jews from Judas, who died soon after the division, and ordered his memory to be held in veneration by them all, as his portion was shared among them. The youngest of the brothers was Joseph, whom the others, fearing his extraordinary abilities, secretly made prisoner, and sold to some foreign merchants. Being carried by them into Egypt, and having there, by his great powers of mind, made himself master of the arts of magic, he found in a short time great favour with the king; for he was eminently skilled in prodigies, and was the first to establish the science of interpreting dreams; and nothing, indeed, of divine or human law seems to have been unknown to him; so that he foretold a dearth in the land some years before it happened, and all Egypt would have perished by famine, had not the king, by his advice, ordered the corn to be laid up for several years; such being the proofs of his knowledge, that his admonitions seemed to proceed, not from a mortal, but a god.

His son was Moses, whom, besides the inheritance of his father’s knowledge, the comeliness of his person also recommended.

But the Egyptians, being troubled with scabies and leprosy, and moved by some oracular prediction, expelled him, with those who had the disease, out of Egypt, that the distemper might not spread among a greater number. Continue reading “Moses and Exodus according to an early Roman Historian”