Continuing from Plato and the Hebrew Bible: Law-Giving Narratives as Greek-Inspired Literature . . . .

The historical narratives of both Herodotus and Thucydides contain narratives explaining the origins of Athenian laws of three notable lawgivers in both myth and history: Theseus, Solon and Cleisthenes. (Russell Gmirkin appears to say that both historians address the latter two lawgivers but I wonder if what was meant was that all three are covered in both works combined.)

So to continue from the previous post with Theseus, the historian Thucydides includes a discussion of the same figure in his ongoing portrayal of the vicissitudes of Athenian constitutional history:

Under Cecrops and the first kings, down to the reign of Theseus, Attica had always consisted of a number of independent townships, each with its own town-hall and magistrates. Except in times of danger the king at Athens was not consulted; in ordinary seasons they carried on their government and settled their affairs without his interference; sometimes even they waged war against him, as in the case of the Eleusinians with Eumolpus against Erechtheus. [2] In Theseus, however, they had a king of equal intelligence and power; and one of the chief features in his organization of the country was to abolish the council chambers and magistrates of the petty cities, and to merge them in the single council-chamber and town-hall of the present capital. Individuals might still enjoy their private property just as before, but they were henceforth compelled to have only one political center, viz. Athens; which thus counted all the inhabitants of Attica among her citizens, so that when Theseus died he left a great state behind him.

Indeed, from him dates the Synoecia, or Feast of Union; which is paid for by the state, and which the Athenians still keep in honor of the goddess. [3] Before this the city consisted of the present citadel and the district beneath it looking rather towards the south. . . . .

The Athenians thus long lived scattered over Attica in independent townships. Even after the centralization of Theseus, old habit still prevailed; and from the early times down to the present war most Athenians still lived in the country with their families and households, and were consequently not at all inclined to move now, especially as they had only just restored their establishments after the Median invasion. . . . (Thucydides, Book 2, 15-16)

We see further summary accounts of the accomplishments of the lawgivers Solon and Cleisthenes in Herodotus:

1.29

and after these were subdued and subject to Croesus in addition to the Lydians, all the sages from Hellas who were living at that time, coming in different ways, came to Sardis, which was at the height of its property; and among them came Solon the Athenian, who, after making laws for the Athenians at their request, went abroad for ten years, sailing forth to see the world, he said. This he did so as not to be compelled to repeal any of the laws he had made, [2] since the Athenians themselves could not do that, for they were bound by solemn oaths to abide for ten years by whatever laws Solon should make.

5.66

Athens, which had been great before, now grew even greater when her tyrants had been removed. The two principal holders of power were Cleisthenes an Alcmaeonid, who was reputed to have bribed the Pythian priestess, and Isagoras son of Tisandrus, a man of a notable house but his lineage I cannot say. His kinsfolk, at any rate, sacrifice to Zeus of Caria. [2] These men with their factions fell to contending for power, Cleisthenes was getting the worst of it in this dispute and took the commons into his party. Presently he divided the Athenians into ten tribes instead of four as formerly. He called none after the names of the sons of Ion—Geleon, Aegicores, Argades, and Hoples—but invented for them names taken from other heroes, all native to the country except Aias. Him he added despite the fact that he was a stranger because he was a neighbor and an ally.

These historical narratives do little more than point to a general historical interest in lawgivers and their innovations, but what I find of more interest is the function of the panegyric as an expression of interest in legal and constitutional questions and origins, and the genre through which most illiterate Athenians would have heard of narratives of their origins and praises for their way of life. Notice especially Thucydides’ reconstruction of Pericles’ speech:

2.37

Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.

[2] The freedom which we enjoy in our government extends also to our ordinary life. There, far from exercising a jealous surveillance over each other, we do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbor for doing what he likes, or even to indulge in those injurious looks which cannot fail to be offensive, although they inflict no positive penalty.

[3] But all this ease in our private relations does not make us lawless as citizens. Against this fear is our chief safeguard, teaching us to obey the magistrates and the laws, particularly such as regard the protection of the injured, whether they are actually on the statute book, or belong to that code which, although unwritten, yet cannot be broken without acknowledged disgrace.

The laws are a source of pride, a national boast. One is, of course, reminded of the similar boast of the biblical laws:

Deuteronomy 4:8

And what other nation is so great as to have such righteous decrees and laws as this body of laws I am setting before you today?

On the panegyric Gmirkin explains: Continue reading “Plato and the Hebrew Bible: Legal Narratives (esp. Panegyrics), continued”

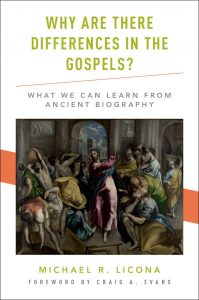

In his recent book,

In his recent book,

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]