A Few More Thoughts

A few months back Neil asked me if I had any further thoughts regarding my hypothesis about a Simonian origin for Christianity. In March of 2019 I had revised it. I am happy to report that four years later I am still quite comfortable with the revision. To me it seems to best account for the many peculiarities of the New Testament and plausibly explains much that can be gleaned from the writings of the earliest heresy hunters. This post is just a summary with a few additional thoughts on the subject.

All Things to All

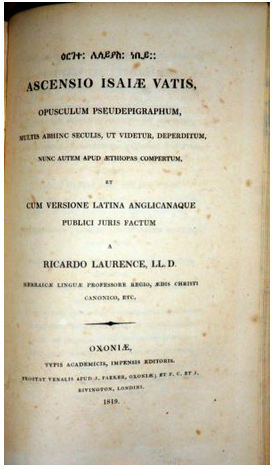

As I laid out in the series, the Simonians appear to have regularly co-opted the religious beliefs of others and twisted them to serve their own purposes. This involved injecting the object of their belief—Simon Megas—into the storylines of other religions and giving him the prominent role therein. Thus they, for example, made Zeus into Simon under another name, and Athena into Helen, Simon’s consort. Similarly, they apparently claimed that their Simon was the mysterious figure whose hidden descent was described in the Vision of Isaiah (chapters 6-11 of the Ascension of Isaiah). The main storyline of that writing is an ancient one, going back, as Richard Carrier points out in his book On the Historicity of Jesus (pp. 45-47), to the Descent of Inanna. But it too was modified along Simonian lines and dragged into their orbit. Most famously, the Simonians claimed that a Jesus who had suffered in Judaea was actually their unrecognized Simon. In short, the Simonians seem to have wanted their Simon to be all things to all men, and so gave free rein to their proclivity for appropriating and modifying the beliefs of everyone else.

The Gospel of Proto-Mark

I think that our Gospel according to Mark is a proto-orthodox reworking of an earlier Simonian version in which the Simonians were again doing their thing. I will refer to the earlier text as Proto-Mark, although it may well be the same as the mysterious Secret Mark. In it the beliefs of a group of Jews about a crucified and supposedly resurrected Jew named Jesus underwent Simonization. If I had to name its author, I would choose Basilides of Alexandria, whom even the heresy hunters acknowledge as the author of an early albeit heretical gospel. He is at the right time, the right place, had the right skills, and–most importantly—had the right mindset: delight in secrecy and enigma. This was the man who, according to Irenaeus, said “Not many can know these [teachings], but one in a thousand, and two in ten thousand,” and “Know everyone, but let none know you.”

Mark owes its enigmatic nature to Proto-Mark. That is, its Simonian author intended it to be understood only by his fellow Simonians. Its “mysteries” (Mk 4:11) were deliberately hidden from those “outside” (Mk 3:32 & 4:11). The key needed for understanding the text was Simonian belief, and that was disclosed only to the initiated. There was indeed an identification secret in Proto-Mark, but I doubt it was the so-called messianic secret. The correct answer to “Who then is this whom even the wind and seas obey?” (Mk 4:41) is Simon Megas. Only later, after the Bar Kochba revolt, or whenever the proto-orthodox became aware of the text and decided to adopt and sanitize it, was the necessary changeover to a messianic secret made.

The Pauline Letters

In regard to the Pauline letters: I still see Paul as the author of some original bare-bones letters. The bulk of the letters as we now have them, however, was likely composed by a circle of Saturnilians, a community founded by the Simonian Saturnilus of Antioch. It may even be that much of the material originally had Simon in view, and that Jesus Christ, Christ Jesus, Lord Jesus, and so on were substituted when it was decided to pass the whole off as Pauline. Who was it who combined Paul’s letters with the Simonian material and formed them into a collection? My guess would be Cerdo of Syria “originating from the Simonians” (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1,27,1) He is from the neighborhood of Saturnilus and is the earliest figure named in connection with the letter collection. And he it would be who likely brought them to Rome shortly after the end of the Bar Kochba revolt. “Cerdo, who preceded Marcion, also joined the Roman church and declared his faith publicly, in the time of Hyginus… then he went on in this way: at one time teaching in secret, at another declaring his faith publicly, at another he was convicted of mischievous teaching and expelled from the Christian community” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 4,11).

Enter the Historical Jesus

Continue reading “A Simonian Origin for Christianity? — A few more thoughts”