Once Clarke W. Owens extracts the Gospels from the Bible and studies them as literary creations on their historical context something most interesting happens. (Owens, I should point out, is not a mythicist. I believe on the basis of his entry in the Christian Alternative website that he is a Christian though one with a radical perspective.)

If you’re one of those readers who has somehow suspected that Christianity as we know it took shape and momentum as a consequence of the catastrophic events of the Jewish War that culminated in the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple then you’ll especially enjoy the way Owens ties the details of those historical events with the literary genre and details of the Gospels.

In the previous post I mentioned Owens’ disappointment that Goulder/Spong attempted to explain the Gospels by reference to the historical context of their authors (i.e. the existence of Jewish Lectionary readings that the authors desired to replace with Christian ones) without taking the next step of investigating why. What would have motivated them to want to do that?

I am not so sure that Goulder/Spong are correct with the lectionary hypothesis, but the real question Owens believes he can answer is “Why did the evangelists write the Gospels at all?” By the Gospels I mean those works that are largely woven together out of the warp and woof of the Jewish Scriptures (and a few related books like Enoch).

Digression on the ‘m’ word

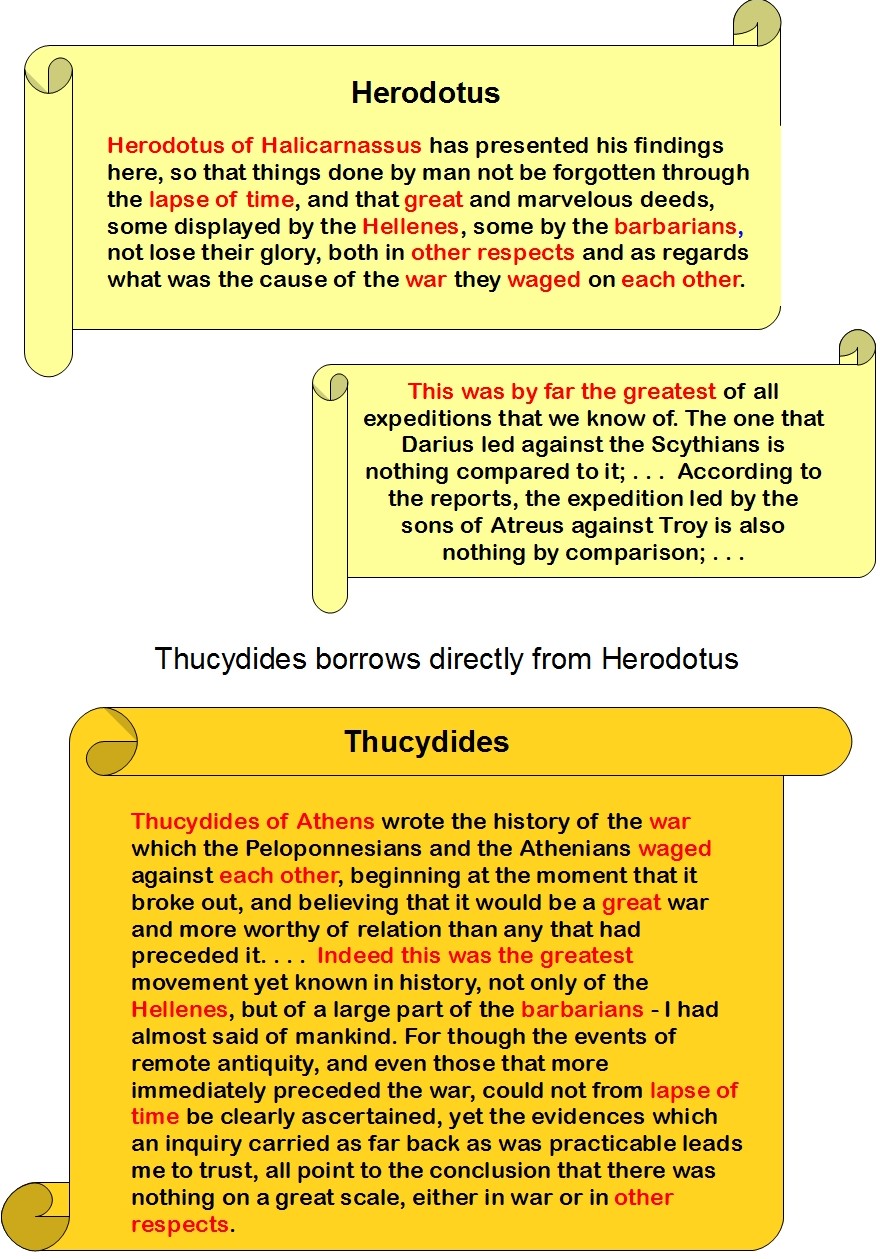

Spong calls this technique midrash; Goulder, I believe, stopped using that term because it raised too many objections among many critics. I have no problem with the term because I have found Jewish scholars specializing in Jewish literature, including the Bible, have also written that the Gospels are largely midrash. If anyone wants to quibble I direct them to my series of posts explaining the use of the term ‘midrash’ in both Jewish and New Testament studies:

- Midrash and the Gospels 1: Some definitions and explanations

- Midrash and the Gospels 2: debates in the scholarly sphere

- Midrash and Gospels 3: What some Jewish scholars say (and continuing ‘Midrash Tales of the Messiah’)

But if you still reject the term ‘midrash’ in this context but still acknowledge that the bulk of the Passion Narrative was stitched together out of dozens of allusions to the Jewish Scriptures, and that so much else in the Gospels are based on passages from the Psalms, the Prophets, the tales of Moses, David, Elijah and Elisha, then follow on. Owens explains why such a form of literature was created to tell a story of a crucified saviour by reference to the historical context of the authors and original readers/hearers.

Literary criticism answering the historical question

Owens finds the answer through a literary criticism that understands a work through the historical context of its creators. He accordingly finds the explanation for the Gospels in the Jewish War as we know it through Josephus. Continue reading “Constructing Jesus and the Gospels: How and Why”