I will continue writing posts in response to Thomas Schmidt’s Josephus and Jesus, New Evidence so this post is a quick interjection before I have the time to write more fully about another Jesus hypothesis that appears to be being widely discussed at the moment — the hypothesis that Jesus was an anti-Roman rebel, a seditionist, in particular, the following book:

I will continue writing posts in response to Thomas Schmidt’s Josephus and Jesus, New Evidence so this post is a quick interjection before I have the time to write more fully about another Jesus hypothesis that appears to be being widely discussed at the moment — the hypothesis that Jesus was an anti-Roman rebel, a seditionist, in particular, the following book:

- Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando. 2023. They Suffered under Pontius Pilate: Jewish Anti-Roman Resistance and the Crosses at Golgotha. Fortress Academic.

(We met Fernando Bermejo-Rubio as recently as my last post, by the way, where I examined his citational support for Josephus writing a negative passage about Jesus.)

The reason I am jumping in early at this time is to flesh out (just a little) some responses I have made in discussions relating to other posts. It’s been a long time since I posted about historical methods, especially as they relate to Jesus, so consider this a brief reminder or recap.

Bermejo-Rubio repeats a common assumption:

As Justin Meggitt has rightly observed, “to deny his existence based on the absence of such evidence, even if that were the case, has problematic implications; you may as well deny the existence of pretty much everyone in the ancient world.”

I responded to Justin Meggitt’s claim back in 2020. It is available here:

Evidence for Historical Persons vs Evidence for Jesus

A few of my other posts addressing the same question of how we know about ancient persons and whether the evidence for Jesus is comparable to anyone else:

- How do we know anyone existed in ancient times? (Or, if Jesus Christ goes would Julius Caesar also have to go?)”

- Comparing the evidence for Jesus with other ancient historical persons

- Jesus Is Not “As Historical As Anyone Else in the Ancient World”

- How do we know any ancient person existed?

- Chart of mythical and historical persons — with explanations

- Historical Research: The Basics

- Doing History: How Do We Know Queen Boadicea/Boudicca Existed?

- The Quest for the Historical Hiawatha — & the historical-mythical Jesus debate

- Did the ancient philosopher Demonax exist?

- Did Aesop Exist?

- Here’s How Philosophers Know Socrates Existed

- Was Socrates man or myth? Applying historical Jesus criteria to Socrates

- Is it a “fact of history” that Jesus existed? Or is it only “public knowledge”?

- The Clueless Search for the Historical Jesus

- One Difference Between a “True” Biography and a Fictional (Gospel?) Biography

- The Historical Jesus and the Demise of History, 1: What Has History To Do With The Facts?

- The Historical Jesus and the Demise of History, 2: The Overlooked Reasons We Know Certain Ancient Persons Existed

- Historical Facts and the very UNfactual Jesus: contrasting nonbiblical history with ‘historical Jesus’ studies (I think this was my very first foray into this debate.)

And a lot more are listed here:

When Historical Persons are Overlaid with Myth

Other statements by Bermejo-Rubio that struck me as misguided:

After all, although some biographies of ancient historical characters such as Alexander the Great and the emperor Augustus contain quite a few mythical elements in their framework, it does not justify our disputing in principle the historicity of the characters themselves . . .

That point is answered in the above posts. When historical figures are overlaid by others — and even by themselves — with mythical trappings (e.g. Alexander as Dionysus, Hadrian as Hercules), we can see clearly where the real human is distinct from the mythical propaganda image.

Inconsistencies and Incongruities are a Common Element among Mythical Figures

Another:

Had Jesus been a construct created out of whole cloth, the accounts about him would presumably have been far more homogeneous. The fact that our sources are systematically inconsistent and are riddled with incongruities is better explained if we assume that a real character on the stage of history was modified in the later tradition.

Quite the contrary. It is real historical figures that emerge with fair measures of consistency; it is the mythical characters who are riddled with contradictions and incongruities. In fact it is the inconsistencies that are part of the enticing mystery and allure make such figures so attractive and believable! See

- How Mythic Story Worlds Become Believable (Johnston: The Greek Mythic Story World)

- Why Certain Kinds of Myths Are So Easy to Believe

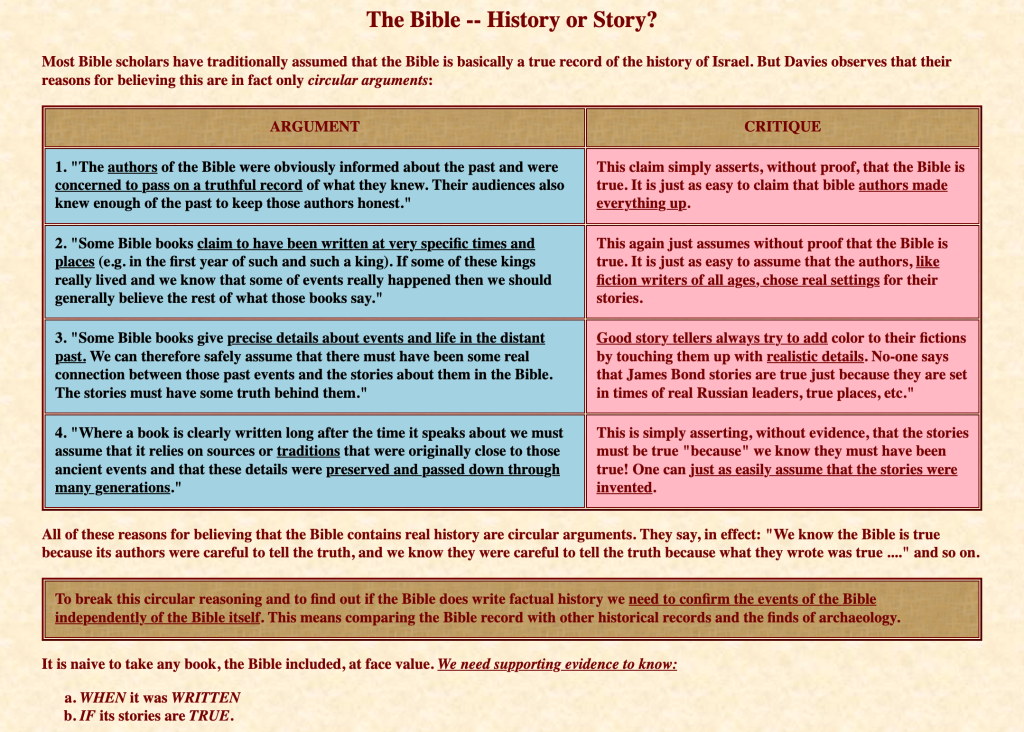

And one page that sums it all up in a simple table:

- The Bible — History or Story? — where I sum up the error at the base of so much biblical studies by distilling the main points of Philip Davies pivotal publication.

But for now — back to work on some other aspects of Thomas Schmidt’s argument for Josephus making a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Christian origins. . . .

But for now — back to work on some other aspects of Thomas Schmidt’s argument for Josephus making a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Christian origins. . . .

(By the way — questions of historicity and authenticity do arise in classical studies, too. I look forward to posting a few instances and comparing how they are approached by ancient historians and scholars with a primary focus on biblical studies.)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neil said in the previous post: “The trial scenes of Acts are taken directly from, and are embellishments of, the trial scenes of Jesus in the gospels — as some scholars have noted.”

I would suggest just the opposite is true. The Jesus of the Gospels is mainly a parable for Paul, the Sower who went out to sow. The author of Mark in particular is validating Paul’s Gospel and Paul’s Jesus over against the teaching of the Jerusalem Way of James the Just. And in Mark’s Gospel the scribes are those come from the chief priest and Satan of the Way, James, to Antioch who causes Peter to become rocky ground to Paul’s seed, and Simon Peter separated like a hypocritical Pharisee from eating with Paul’s Gentile believers. And in Mark 14, Simon [Peter] is a leper who should separate but does not, a real hypocrite. Mark is really roasting Peter and the Jerusalem Way of James the Just. We can assume that Paul’s difficulties on his last Passover to Jerusalem were well known to Mark’s church at Rome. So yes, the Jesus of the Gospels is fictional, but more precisely parabolic.

Hi Stephen — I see you beat me to commenting here. I had planned for the following to be the first comment, but no matter, it covers some of what you have said here anyway… Here is my original post:

I posted the above to find a more suitable space to discuss questions of historicity and the New Testament/Christian origins. Here I want to reply to a comment that was posted in another thread:

Hi Stephen. You wrote:

Take your point

That is how Acts has been interpreted especially since Walter Bauer and his Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity. But it is only one of a number of theories about Acts and it is not accepted by all scholars. To begin, we have no independent evidence there ever was a historical Paul. Nina Livesey is one of the latest scholars to question his existence, though she is not alone. https://vridar.org/tag/livesey-letters-of-paul-in-their-roman-literary-context/ The “Jerusalem Way” is a construct of Acts though embellished by some other scholars with snippets from the DSS and other patristic writings. Again, we have no evidence it was a “real thing”. But we do have some second century ideas that would well explain why such figures were fictionally created.

In fact, many scholars have long been puzzled by the inconsistencies between Acts and Galatians. They are not consistent. Was Galatians responding to Acts or was Acts trying to correct Galatians? That is a major debate. If James was a pillar of the church he was a very poor pillar to allow thousands of his flock to mob the streets calling for the lynching of Paul. He has no control over the church at all in those scenes. Why couldn’t and Peter and John simply teach tolerance and respect towards Paul?

And why were the Romans so helpless all of a sudden? They had the power to crush any mob but they didn’t. They let them rule the streets. That’s not historical. It runs against everything we know about Roman power — especially if, as we are told so often, Judea was at that time a hotbed of troubles. Roman weakness at that moment is an embellishment of Pilate’s weakness before the Jewish mob. Totally unrealistic.

Perhaps or maybe not. It’s only a theory that I don’t know can be confirmed. I don’t mind theories but I do keep them in the realm of theories and not confuse them with facts. At least I try. But Mark’s gospel has also been interpreted by scholars as painting a family union between Jews and gentiles on the one hand, but also as being anti-Jewish apostles (Peter, James and John). Others read the gospel as very sympathetic to those apostles despite their failings.

Acts can be seen as based on the founding story of Rome. As Troy was destroyed a small band of Trojans escapted and wound their way through tribulation after tribulation, via Carthage where their mission was almost dooomed, on to found a new Troy at Rome, a city destined to rule the world in righteousness. That’s the story of Acts, too, written in hindsight after the destruction of Jerusalem. Paul’s capture at Jerusalem is the counterpart to Aeneas’s “capture” at Carthage. The new church is based at Rome and is an ecumenical church, opposing extremists on all sides (gnostics and Judaizers) but bringing the majority into one larger compromise.

“Acts can be seen as based on the founding story of Rome.”

I would not say Acts is exactly based on that story, but imitation was common in the ancient world. The Gospels and Acts were written for Gentile audiences, so they might well imitate the Greek/Roman classics.

The main consistency between Galatians and the second half of Acts is that James did not approve of Paul’s Gospel to the Gentiles and to the Jewish Diaspora (Galatians 2:9-16, Acts 21:20-22). It is evident in Galatians that Paul was also preaching his Gospel to the Jews in Antioch, because the Jews were eating with the Gentiles. But this was against Moses and the traditions if these were non-kosher foods. This mainly had to do with foods, but also included the issue of circumcision, with Paul preaching that was no longer really necessary. Galatians came first, and Acts much later.

I assume the chief priest of the Way, James, set Paul up (betrayed Paul to the Judas Sicarii with a brotherly kiss) when James tasked Paul with the Nazirite vow. The Jewish zealots and Judas Sicariots of the Way could then accuse Paul of bringing Gentiles into the court of the Jews. But the Roman’s saved Paul’s rear end. That is why we have the parable of the forty assassins conspiring with the chief priests [of the Way] in Acts 23 to kill Paul and the Roman’s guarding him. The Quisling high priest Ananias contented himself in Acts 24 with accusing Paul of sedition along with the rest of this seditious Nazarene sect.

I’m not with you, sorry. Are you saying Acts could have been imitating the Aeneid? If so then that by definition surely means it was based on the Aeneid (Rome’s founding story).

One needs to look at all the details and balance them all. Scholars are flummoxed over the inconsistencies. Shelves of books have been written about the problem.

Does it not raise problems in that this was not addressed by Jesus himself? Did not Jesus teach them about foods and clean and unclean? He did eat among gentiles in Tyre, for instance.

But on what grounds can we believe Galatians is a genuine historical record? The ancient world was not only big on imitation but also on fictionalized letter-writing. Names like Seneca would teach readers his philosophy by creating the name of a regular addressee that readers could imagine was real. More interesting for them to imagine they are reading correspondence between two private persons than a letter sent directly to them. I’m not saying Galatians definitely was fiction, but there is a very sound historical case that it could be so. We can’t just assume it is by an authentic Paul to authentic Galatians. The same applies to any letters and writings in the ancient world. The same standards have to be applied to all.

I recently completed a formal study unit that included investigation into a popular historical letter known among Romans. Scholars don’t assume it was authentic. They debate the pros and cons. We don’t see that in the case of the so-called “authentic” letters of Paul. They have always just been assumed to be authentic because they share a common style, supposedly (though they don’t really).

We don’t know that Acts came after Galatians. That is only an assumption or a theory. Some scholars disagree so it is not a fact. There are good arguments both ways.

One of my biggest problems with many biblical scholars is that so many of them talk as if their pet ideas, or those shared by their friends, are the only truth. That is not honest communication with lay audiences. Normally in other areas scholars will try to explain the diverse views in their field and explain where their own view fits, whether it’s a minority view or not.

—-

Postscript — to directly address a point in your earlier comment:

Why assume the names of the characters in Mark’s gospel are real or historical? Don’t we normally have some reservation about “realism” when we are told a story where a lead character has a name that is a pun or play on the very type of character he is?

Socrates, for example, tells us a story of how he was taught by Diotima of Mantinea. We are immediately suspicious when we realize the name can be translated from the Greek as Fear God from Prophetville. That the name Peter, the leading disciples, means “rock” and the fact that he fulfils the rocky soil of the parable in the Gospel of Mark should alert us to something about the fictional character of the story. That’s not proof, but it is a warning sign. Certainly most of the names in the Gospel of Mark can be interpreted as symbolic puns on their roles in the narrative.

The entire story of the rift between Paul and the Jerusalem church can well be explained as an aetiological fiction to explain second century “proto-orthodox” Christianity opposing Judaising Christianity. Take the heresies described in Paul’s letters for example. There is no evidence that the kinds of heresies he addresses existed in the first century but they are a widespread feature of the second century. If Paul had written what he did in the first century then surely people could have seen that he denounced the second century heresies. But if there were no such Paul or writings in the first century, it is easy to see how Paul could be fabricated in order to denounce what was rife in the second century — and have him backdated to the fictional pioneering days. That is not a proof, but it is a simpler explanation that explains why we have no first century evidence and why Paul and all of these features suddenly appear in the second century.

Acts and the Gospels might “allude” to any of the ancient Greek/Roman classics or Hebrew scripture in telling their story as a way of reinforcing their own story in the mind of the Gentile reader or hearer. Mark’s Jesus and Paul are like Odysseus (in my opinion), traveling around land and sea casting out monsters and demons, and revealing themselves at the end as the true son of God who defeats their enemies by resurrection from the dead. Perhaps Acts is like the Aeneid with the church at Rome being founded in the same way that Aeneas mythically founded Rome. I had not thought of that until you mentioned it. But according to scholars, this was a common narrative practice then and now to allude to older classic narratives to reinforce one’s own narrative in the mind of the reader/hearer.

There are inconsistencies between Acts and Galatians because Acts is a much later account and not directly from Paul. The first part of Acts has its own tendenz to reform the Jerusalem church in the image of Paul to legitimize Paul and Paul’s Gospel in the same way the Gospels do, with their Jesus spouting Paul’s doctrine. The latter part of Acts does seem to have some historical knowledge of Paul and Paul’s difficulties with the Jerusalem church of James, but wants to obscure (parable) the fact that the “chief priests” of the Jerusalem church want to kill Paul. This is something of an embarrassment for the early Gentile churches, because if the Jerusalem church wanted to kill Paul, then that probably meant the historical Jesus would also have wanted to kill Paul. That certainly would have been an embarrassment to Paul’s Gentile churches. And not to mention, Paul himself has a tendency to obscure his true relations with the Jerusalem church, saying all the time he is not lying, which of course he is lying, constantly.

No, the Gospel Jesus did not teach all foods are clean. Paul taught that, and the later Gentile churches put those words in the mouth of Jesus to legitimize (give authority to) Paul’s teaching. So if later James and the Jerusalem church are saying something different, then that is going against the teaching of Jesus and it is they who are the heretics that have fallen back into Judaism. Paul is the true teacher of Jesus’ doctrine, or so the Gentile churches of Paul say and legitimize in their Pauline Gospels.

Galatians would seem to be historical based on Paul saying he was at odds with James and those come from James and that he owes nothing to them. But in the Gospels it is Jesus who is made to endorse Paul’s teaching. It seems to me one would have to be historical and the other not. The Roman Church and Church Gospels simply believe that Paul is correct, and James and the Jerusalem Way (the Poor or the Ebionites) fell back into Judaism, rejecting Jesus’ own teaching. But of course they didn’t. They rejected Paul’s teaching and Paul’s Jesus. The Church Gospel Jesus is based on Paul’s lies.

We really don’t know how historical the names are in the Gospels. For example James and John in Mark’s Gospel, the so-called sons of Zebedee, are possibly the narrative’s way of alluding to James the Just and John of Patmos. These two were both at odds with Paul’s doctrine, and they were both at odds with Paul’s Jesus, wanting all the kingdoms and power and glory of this world, carnal things, or so the narratives say.

Neil’s: “The entire story of the rift between Paul and the Jerusalem church can well be explained as an aetiological fiction to explain second century “proto-orthodox” Christianity opposing Judaising Christianity.”

That is certainly an idea worth looking into. But there is no question in my mind that the Jesus of the Gospels was created specifically to legitimize Paul and Paul’s teaching in his letters over against the so-called heresy of James and the Ebionites. Therefore, the Gospels do not come first, Paul’s letters do, and the Gospels are meant to mirror Paul the Sower’s teaching, and the difficulties Paul had with Peter, James, and John, the Pillars of Judaising Christianity.

Therefore, when the Gospels talk about “scribes (teachers of the Law), and hypocritical Pharisees (separatists), and murderous Jewish chief priests conspiring with Judas Sicariots”, these are all actually a euphemism for Paul’s own Jerusalem church. Actually quite embarrassing. No wonder why Eisenman says these are “euphemisms” for those of the “Jamesian persuasion”.

But there is no question in my mind that the Jesus of the Gospels was created specifically to legitimize Paul and Paul’s teaching in his letters. But Mark’s Gospel is also quite aware of Paul’s last Passover to Jerusalem as described in the last “historical section” of Acts. Acts 21, 22,23,24 is too embarrassing to relate unless it actually was historical. But even then, the 40 assassins conspiring with the “chief priests” is made into a parable to hide the fact the 40 are Judas Sicariots sent by James to kill Paul. And this is what we see in Mark’s passion play and the conspiracy between the chief priest and Judas the Sicariot to murder Jesus.

>Acts 21, 22,23,24 is too embarrassing to relate unless it actually was historical.

The fact that neither I nor any other person whom I have read about has ever encountered the criterion of embarrassment used outsider studies of religious texts suggests strongly to me that the criterion of embarrassment should not be taken seriously in determining what really happened in an allegedly historical text. Indeed, the Criterion of Embarrassment diffused into studying Buddhists’ texts from Christian studies rather than from history.

In the writings of the scholar of Buddhism Jan Nattier, specifically her book about Mahayana Buddhism “A Few Good Men: The Bodhisattva Path according to The Inquiry of Ugra (Ugraparipṛcchā)” [University of Hawaii Press; New edition (May 31 2005)], Nattier uses the term “principle of embarrassment” and refers to the term as “commonly used in New Testament studies” on page 65. She claims that she was introduced to the term by David Brakke.

“The fact that neither I nor any other person whom I have read about has ever encountered the criterion of embarrassment used outsider studies of religious texts suggests strongly to me that the criterion of embarrassment should not be taken seriously…”

Interesting observation. But maybe it means it should be applied in other fields in addition to religious studies? I’m not a historian, but it’s always struck me as a sound principle; and I suspect not nearly enough skepticism is applied to most historical received wisdom.

Have a look at some of the articles linked in the post. Establishing “facts” through “criteria” in the way biblical scholars often do logically fallacious — as more and more biblical scholars themselves are pointing out — and if you mention it to historians in other departments be prepared to be met with rolling eyes. Other historians have expressed dismay at the baselessness and illogicality of certain biblical studies approaches.

Yes, but I was thinking that having a criterion of embarrassment at least implies that criteria for acceptance of a historical datum are necessary, i.e. you shouldn’t accept anything in the sources without some good reason. As I said, I suspect that is widely ignored by historians in other fields, whose work isn’t subject to nearly as much scrutiny.

Are the problems in religious history unique to that field, or is religion here, as often, the canary in the coalmine?

I point out in the linked articles in the post above how historians determine what is a reliable historical fact or person. Criteria of embarrassment or anything else doesn’t enter into it. Some of my posts on this criterion: https://vridar.org/tag/criterion-of-embarrassment/

Historians’ works are very tightly scrutinized — far more, I think, than many works of biblical historians. Where there is room for doubts in the evidence they will debate the historicity but I don’t know off-hand of a case where they decide the issue on biblical studies criteria.

Take one instance. Many scholars say that no-one would have made up the “embarrassing” notion that Jesus came from some obscure village like Nazareth. Too embarrassing, etc. But wait — a main idea about Jesus is how he humbled himself to the lowest to become the highest in the end. So why would it be embarrassing?

Besides — compare pagan mythology. Do you think a great god, Apollo, would be given a lowly, desolate, god-forsaken place that everyone shunned as his place of birth? Would anyone make that up about Apollo? But that is exactly what the Apollo myth says. He was born on a desolate rocky crag in the middle of the sea — in a place despised and shunned by all. Does that mean Apollo really was born on Delos?

https://vridar.org/2023/03/15/from-humble-beginnings-a-tale-of-two-divinities-jesus-and-apollo/

You make a good point: the application of the criterion of embarrassment is tricky – one man’s embarrassment is another’s humbleness. Perhaps it’s so tricky as to be rendered useless.

But surely the studies of e.g. Caesar and Alexander are not as emotionally fraught and contentious as the study of Jesus. There’s a Conventional Wisdom in historical matters which is seldom challenged. As kid I was taught that the US Civil War was fought over states’ rights, and slavery was a secondary issue. That conventional wisdom was blessed during Reconstruction and endured for a century because it kept the history industry and the country at peace, and only began to change during the Civil Rights era in the 1960s.

A related issue: historians would still be rejecting the hypothesis of Thomas Jefferson’s affair with Sally Hemings if not for developments in DNA in the last generation.

There are many pious truths which are accepted not because of convincing evidence, but because no one has any interest in questioning them. I think a Jesus Seminar style investigation of many of them would be salutary.

You are hitting on a major issue in historical studies. But there is a difference between interpretation of the data or facts or events, and investigating what actual events happened or persons existed.

With the Civil War interpretations, with two views presenting opposing explanations for what it was all about, the causes, etc — what is happening there is that different historians give different weight to certain events, they argue over the relevance of specific events. Some stress one set of facts against others.

But the facts themselves, or the particular events and actions, — these are generally discoverable by much the same techniques researchers and archivists and detectives have always used to disover “what happened”.

Some historians even try to steer others away from even looking at certain questions over certain events — they might even accuse interested persons of having evil motives. The history of Palestine and Israel in the past 100 years is one case in point. So there can at times be hostile debates over historical accounts. The US has had its “history wars” as has Austalia — and as India is experiencing with some violence right now.

Some historians unfortunately do insist their interpretations are “absolutely true” and even “facts”, but it is important, of course, to be alert to the difference between an interpretation and theories and explanations of events — and the actual events themselves.

Yes, ancient authors imitated “masters”. And when they did we can see they were writing fiction, not history. Virgil was imitating Homer — both writing fiction. If a historian like Josephus wanted to impress with his historical work he imitated another historian, Thucydides, and sought to follow the same standards of “getting his facts right”.

It is very evident that certain gospel stories are based squarely on certain OT stories. The conclusion is that those gospel stories are made up — they are rewritten OT stories. That is the simplest and most obvious explanaton. A classic example is Jesus feeding the multitudes. There is no question that those scenes are based on Elisha’s miraculous feeding of disciples with a few loaves. Now anyone can simply assume that “what really happened historically” is that something prompted the crowds to share their food and the story got transformed into a miracle, but that is an entirely unnecessary and baseless speculative explanation for the story. The story was a rewrite of an OT miracle.

If we can see a story is based on fiction then it is most simply explained as being fiction — unless and only unless there happens to be independent evidence that some historical events happened in a way quite similar to some fictional tale.

Why do you assume the stories and names have any historical basis at all?

Neil, can you refer me to a few of the scads of books on the conflicts between Galatians and Acts? I know there are many such conflicts; and Acts is even in conflict with Acts on, I think, the road to Damascus tale which occurs at least 3 times there. Maybe you have a prior post you could refer me to?

On the priority of Galatians before Acts, I always made the call based on the fact that Acts opens with a claim that it’s being written by the author of the Lukan gospel, whereas neither Paul nor John of Patmos show any sign of familiarity with any of our four gospels. Not that that’s necessarily conclusive, but it’s something. What’s the counter argument? Thanks.

Wikipedia has an article on the “Jerusalem Council” which some think Paul relates in Galatians 2, and Acts in chapter 15. Robert Eisenman suggests that the council may not have been as harmonious as Paul portrays. In any case, Eisenman suggests that Paul delivered the softball message to the Gentiles of Asia, then the Jerusalem church emissaries followed that with the hardball message to become Jewish and assist with a war against Rome. In particular Eisenman suggests this is how Adiabene came to assist the Jews during the first revolt in 66-70AD. Paul and Ananias delivered the softball, then those come from James followed with the hardball. Adiabene had its own vested interest as a client state of Parthia. The Jewish rebels were always seeking help from the Parthians, which only added to their sedition in the eyes of the Romans.

Where to begin? I don’t think I’ve ever read a scholarly commentary on or discussion of either Acts or Galatians that hasn’t in some way attempted to explain, reconcile, set aside, …. conflicts of some kind between Acts and Galatians, both in relation to specific events and character portrayals. These conflicts are also at the heart of many discussions that seek to set a chronological cum ideological rationale for the relationship/order of composition of Acts and Galatians. I visited a theological library in Sydney last year and was overwhelmed by the rows of books dedicated each to Acts and Galatians. I gave up attempting to compile a reasonably comprehensive collection of relatively recent works on the specific questions I had relating to Acts, Galatians and Paul.

If you have something specific in mind it might be easier for me to single out a few titles of books or articles. (Even my Zotero list is bordering on the unwieldy in each of Acts, Galatians and Paul as a person.)

I have had to become more open to Acts or an earlier form of Acts preceding the Pauline letters since reading Nina Livesey’s latest book (that I posted about not too long ago). Nina renewed my confidence in returning to some of Hermann Detering’s articles and imagining the entirety of Christian origins being a second century project. Nina also posits at least some form of Acts being written prior to Paul’s letters — and even suggesting that the name/figure of Paul so central to Marcionism originated as a Lucan invention in Acts. (Though I don’t know if an original form of Acts should be associated with Luke.)

I’m not committed to any of the Gospels or Acts predating Paul’s letters but nor have I shut my mind to the possibility.

Well, I was just playing around with some ideas of literary construction, and I see that in Paul’s chronology at the beginning of Galatians, he has his conversion (no details) and then goes to Arabia and then Damascus, whereas in Acts he keeps telling us about his conversion on the road to Damascus. I wondered if it is even worth mentioning this, or is everyone going to say oh, that’s an old saw, we deal with it this way or that way, etc. Other little things like that.

Pretty much everything I recall reading (though it may not be much more than you have read) is focussed on the historical/biographical chronology question arising from the two accounts (Acts and Gal). I would be fascinated to read your literary approach. A few items that might by of some interest:

I copied the info, thank you. I’m doing some notes & will let you know if it leads anywhere.

How might the arguments concerning valid and invalid historical methods that I present in the above post stand up in a formal classics or ancient history department at one of the universities in the top 1% of world rankings? I have been undertaking a preparatory course before taking up a Masters in Ancient History and have today received my first semester results. In the history element of the course I consistently applied and justified the same methods I explain in the posts linked above. I sometimes drew upon a few of the source materials I have used in those posts. The results have been high disctinctions in foundational units for both ancient Greek and historiographical and historical studies. My major essay was assessed in part: “Your detailed and perceptive critique of modern scholarship on the central question of authorship is very well argued.” I take some encouragement from these results, especially given the number of hostile critics I seem to have attracted in various forums. It is nice to be reassured that what I post here can be transferred to formal studies and be acknowledged as reasonably sound and well sourced arguments. I hope to continue to improve my standards the more I learn and the more feedback from disinterested academics I am given. (Excuse this little boast.)

Neil, I don’t know who your question is intended for, but I’d like to comment. I sure can’t speak for the top 1% of university faculties, so I don’t know how you’ll do. But I know you have a fair and logical mind with a good bias detector. I’m waiting for the Schmidt discussion to get the point where we say that his argument is intended to bolster the claims for authenticity of the Testimonium based on its imagined hostility to Jesus. I can’t remember when I’ve disagreed with anything you’ve said about historical methods. The inset from 2014 has the basics about what is needed. We don’t have all those things with Biblical studies, but that doesn’t stop the Biblical scholars from continuing to classify as history things that are properly classified as myths. Like gospels. The hostile responses you provoke on other websites derives from the fact that Christianity starts with a cultural bias that began 1700 years ago, not with flaws in your methodological theory. All of Vridar is infused with a calm, clear-eyed resistance to this bias, which is why I’ve been reading your blog now for, what? Over 10 years. Looks like you’re doing pretty well so far with the studies!

A moment of feeling low down, some despair, sorry. I let it show this time.

Correction to earlier post: I meant to say “to get TO the point”, not “get the point.” Because I know that’s where it’s going. Post meant to be encouraging.

No problem. I took it that way. Thank you.

The .info page on In Search of Israel has the two parts not linked. Is that a web error or did you not complete the pages?

Thanks for blogging!

Do you mean “Origins of the Israel of the Bible’s narrative” and “Who wrote the Bible books, and where, how and why?” ? Yeh, I never got around to completing those sections, unfortunately. I have left them there always still intending “one day” to complete that. (Though much has been learned since.)