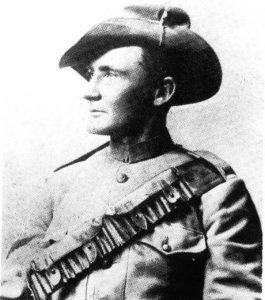

Years ago I walked out of a movie theatre enraged. Thousands throughout Australia at that time did the same. People talked about it for months afterwards, asking “How could they do it!” The “they” were the British colonial masters led by Lord Kitchener; the “it” was the execution of two Australian soldiers as scapegoats to protect the international image of Great Britain. The film was Breaker Morant, based on historical persons and events in the Boer War at the turn of the last century. Morant, nicknamed the Breaker, was a national hero few of us at the time had even heard about. The film revived memories from the early twentieth century that the Breaker was very much a national hero and a sacrificial victim to the British overlords.

Morant has gone not so much into history as into legend. He followed the admired track of other Australian folk-heroes — Ned Kelly, Moondyne Joe, Captain Starlight. They were all men against authority; good bad men or bad good men, always with enough human appeal to disguise the fact that they were outside the law, that they robbed and killed and were brought to book. Behind them all are the near-mythic figures of Hereward the Wake and Robin Hood, of William Tell and the outlaws of the Old West. People prefer to think of them all as bold and brave individuals, self-reliant and strong, defiant against great odds. Morant, in the popular mind, has joined their company.

(Denton in Closed File, cited by Walker, pp. 18f )

Here are the facts about Morant according to Shirley Walker’s article ‘A Man Never Knows His Luck in South Africa’: Some Australian Literary Myths from the Boer War. I list them first so you can begin to wonder how such a figure was able to acquire the status of an Australian mythic hero.

- His name was Edwin Henry Murrant, son of the Master and Matron of the Union Workhouse, Bridgewater, Somerset.

- He lied about his age to marry Daisy O’Dwyer, soon afterwards deserting her and eventually remarrying as a bigamist

- “A young English scapegrace consigned to the colonies for some youthful escapade”

- He had a reputation for defaulting on debts

- A “womanizer”. His nickname Breaker referred to both his breaking in of horses and his breaking of women’s hearts

- A horse thief

- A regular drunkard

- In the Boer War he shot prisoners, including a number who entered his camp under the white flag.

- He also had witnesses to these crimes, including a missionary, murdered.

- On being caught he was tried and executed by firing squad.

There was a positive side:

- He was “well known throughout Australia (i.e. the colonies) as a rough rider, a polo and steeplechase rider”

- a bush poet published in the leading magazine, The Bulletin, under the pen-name “The Breaker”

How does one make a Hereward the Wake or Robin Hood type hero out of raw material like that?

First, one needs the right soil for any seed to germinate. Or, to change the metaphor, one needs a mold by means of which to cast the person to become the hero.

In other words, the ideas of the myth are “out there”, in the minds of an audience who are prepared to love the idea of finding exemplars to fit those ideals.

Imagine, for example, a situation in Judea in the Second Temple era, where people are filled with ideas of heroic resistance against imperial powers, such as came to be exemplified by the Maccabean martyrs. If such ideals and images inspired large sections of a population who were subject to another imperial power, Rome, then anyone executed by that power (for any reason, even, say, piracy or murder) might soon start to be re-imagined as another heroic martyr in the tradition of the Maccabees. In another time with a different cultural mindset the same person might simply be viewed as a common criminal deserving his fate.

Australians in the 1890s were acquiring a political and literary consciousness of their “national” identity. This was the time of popular movements in support of Federation, of uniting their separate British colonies to become a single independent nation. The shearer’s strikes at the time also contributed to their sense of defiance against unjust masters and confidence in their abilities as a collective “mateship”. And it was a time when the great poets and story tellers, Henry Lawson and “Banjo” Paterson (author of Waltzing Matilda and The Man from Snowy River), captured the popular imaginations with their portrayals of the “Australian character”.

The favoured self-image was that of a nation of “battlers”, all individuals, facing great odds with courage and swagger and, above all, acknowledging no authority. . . .

With Lawson and other writers, Paterson had been responsible for the image of the Australian bushman as a superb horseman — resourceful, independent, a humorist and, above all resentful of authority.

(Walker, p. 2)

Paterson went to South Africa as a journalist to report on the Boer War but left before the worst atrocities were committed. He sent back reports valorizing the Australian soldiers, depicting them as typical of the Australian ideal character that was being being cultivated back home.

What is of more interest however is the way in which Paterson’s despatches fostered a mythic view of Australian prowess in war based, as was the myth of the 1890s, on courage, equestrian skill, the ability to survive in rugged country, and an aggressive independence. When one considers that “independence” could mean a reluctance to be ordered about, that “the ability to survive” could refer firstly to the Australian ability to live off the land (that is by stealing from Boer farms) and secondly to the legendary Australian talent for horse-stealing, from the officers’ lines or from other units, it is obvious that the popular self-image which Paterson fostered contained the seeds of conflict with authority.

(Walker, pp. 4f)

Paterson’s newspaper reports made rousing reading throughout the colonies/new Federation:

The wide circulation of Paterson’s despatches through the columns of The Sydney Morning Herald guaranteed the currency of his views. Sold to the Australian people at a time when they were peculiarly receptive, at a time of national pride in the coming Federation, this mythic view prepared the way for national outrage when it was challenged by allegations of malingering, of cowardice and of cruelty.

The Paterson view of the Australians abroad owed much to his persistent emphasis upon the value of the Australian troops, on the fact that they were almost always placed in the foremost line, on their superior ability to survive as bushmen, on their disciplined and humane attitude to the Boer farmers, and on individual acts of great courage, usually by someone well known in Australia — The Hon. Edward Lygon, for instance, “Lord Beauchamp’s brother”; Major Bayly, “well-known in Sydney”, or “the son of Sir Joseph Abbott”.

(Walker, p. 5)

As you might guess, Paterson happened to downplay the real atrocities. “Burning of Boer homesteads … deplorable but necessary”; “deaths, while sincerely regretted, are always muted by instance of true ‘grit’ and heroism…” The battles were portrayed from the panoramic perspective, never to zoom in on close-ups of horrific reality.

All this, then, fostered the establishment myth — of war as a gallant and necessary enterprise in aid of the empire, of Australia as a nation moving towards maturity and demonstrating this by the courage of its superior (if somewhat rakish) young men.

(Walker, p. 5)

Thus the mold. What raw material was at hand to pour into it?

First, the trigger event. Something happened that catapulted Morant into the mythic mold.

Morant’s trial, early 1902, was undertaken in haste, so much so….

the Australian Government was not at any stage consulted, or notified of the execution, and the transcripts of the courts martial have never been made available.

This then is the raw material of myth, and a fine myth, both popular and literary, has evolved. It is a myth of national self-justification with Morant as a representative Australian figure. His faults are freely admitted, but these — drinking, womanising, fighting, carelessness with debts and the appropriation of horses — are at least part of the national “macho” image. The traditional Australian virtues — independence, the ability to “clean up” in a rough situation and, above all, loyalty to ones mates — are emphasised. Morant, like Ned Kelly, has become a mythic hero, and the mythic hero must conform to as well as create the national self-image. Furthermore he must be seen as a victim of the British in order to conform to national xenophobia and a false sense of national maturity, of release from the mother. The mythic version is melodramatic, adolescent, and has proved itself irresistible.

(Walker, p. 10, my emphasis)

Here’s how it happened in the literary accounts, step by step:

Frank Renar (Frank Fox of The Bulletin), Bushman and Buccaneer, 1902

Soon after Morant’s execution a reporter for Australia’s premier magazine, The Bulletin, wrote of the events. Under the name of Frank Renar he included a selection of The Breaker’s own verse,

thus giving not only the “factual” account (based, according to Renar, on “trustworthy documentary evidence”) but also proof of the high sensitivity of the victim Morant.

(Walker, p. 10)

All subsequent accounts followed Renar’s method.

Renar actually appears on a face value reading to be even-handed in his account. But careful attention to his prose shows an emotional manipulation at work. The purported historical pretext for Morant’s atrocities was his confrontation with seeing the mutilated body of his friend, Captain Hunt. But notice the way Renar presents this moment so as to win over the readers’ sympathies for all that Morant is about to do as a consequence:

With grim hearts the men rode out from Fort Edward, Lieutenant Morant leading them, sternly set upon avenging the blood of a comrade and wiping out from their own names the stain of cowardice. When men move in such a mood it is ill for those who chance to meet them. . . . .

The body was there, sorrily mangled in truth — whether in loathsome spite or in sad but unavoidable happening of battle no man can say with certainty . . . [Morant’s] heart grew more savage, and his face took a sterner set as he saddled up again and followed on the track of the Boers. Not war but vengeance was in his mind.

(Renar, cited by Walker, p. 11)

Walker aptly comments on Renar’s portrayal:

Here the mythic dimension, obviously that of the Germanic heroic tradition of the comitatus, is gratuitously imposed upon raw material which is essentially sordid.

(Walker, p. 12)

George Witton, Scapegoats of the Empire, 1907

The next account to appear was by one Morant’s companions, the only one who escaped the death penalty, George Witton, author of Scapegoats of the Empire, 1907. Witton stressed Morant’s nobility of feelings for a wronged friend. He also introduced into the legend the claim that Morant himself had falsely made, that he was of high birth of a noble English family. The title of Witton’s book gives away its theme: Morant was a scapegoat, a victim of injustice. The true villain is no longer Morant but Lord Kitchener. Morant is presented as one having initially rebelled against orders supposedly from Kitchener to kill all prisoners or at least take no prisoners, but who only turned around to obey Kitchener’s order after the death and reported mutilation of his friend Hunt. Kitchener is said to have absented himself during the trial so he could not be called to account. In actual fact (though not reported in Witton’s account) Kitchener had evidence that Morant had murdered the witnesses to his crimes. Witton also arranged to have released a letter that was evidence that Morant had indeed admitted guilt for the murder of one of those witnesses, the missionary, only after 1970. By then, of course, the tide of myth had surged well inland.

Major C. S. Jarvis, C.M.G., O.B.E., Half a Life, 1943

Jarvis wrote in the “stiff upper lip” style of British colonial masters, ironically revealing more of the truth about Morant than we had read previously:

My sympathies have always been with the unfortunate man, for I knew and liked him, and moreover one has the feeling that, but for the existence of men of his somewhat ruthless calibre during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the British Empire would not now be the envy of all her neighbours. There were many rough paths to be hewn out of the world between 1750 and 1900, and it was the men of Morant’s type who did the work.

(Jarvis, quoted by Walker, p. 14)

F. M. Cutlack, Breaker Morant, A Horseman Who Made History, 1962

Cutlack introduced more than previously the idea that the British authorities had something to hide over the Morant trial and execution. The British War Office had officially informed Cutlack that the court martial transcripts were “no longer in existence”. It eventually turned out that the reason they had not found their way to London was the result of some administrative incompetence and that they did still exist in South Africa. But Cutlack at the time was not aware of that.

The next account was that of

Kit Denton, The Breaker, 1973

Kit Denton much later admitted that his book was principally fiction:

At the time … I was concerned to write a good story, to write it as well as I could, and to put into it the sorts of marketable factors for which plain professionalism called.

(Denton, quoted by Walker, p. 18)

Despite these later admissions of fictionalizing Morant’s life Denton’s 1973 book has at the time of Walker’s article remained the “most romanticised” and “most popular” version of The Breaker’s life.

Even in that first account Denton offered a warning to the astute:

There was a Breaker Morant. He lived his life in the limes and company of the people mentioned in this story, and he went through much of the action in these pages … I’ve departed from history only when the facts weren’t discoverable or when I felt it was necessary in the interests of a good story . . .

(Denton, quoted by Walker, p. 15)

The myth might be said to have come of age:

In The Breaker the stereotype is exploited to the utmost. The womanising, drinking and brawling are glamorised and made to appear somehow heroic, while Morant is seen as a sort of John Wayne of the Australian frontier, a “centaur” who leaps into the saddle with bird-like grace, who disregards injury:

I wonder … I wonder, if you’d mind shaking the other hand! I think that arm’s broken (Denton, p 38)

and whose passion, when aroused, is terrible.

(Walker, p. 15)

Too late for the truth

Subsequent historical accounts of Morant (Margaret Carnegie and Frank Shields, In Search of Breaker Morant, 1979 and Kit Denton’s follow-up work, Closed File, 1983) have uncovered a more truthful narrative, one that finds Morant guilty as charged, and moreso, of horrific murders in South Africa. But too late. The myth has been born. As Walker remarks,

Although the two most recent re-workings of the affair completely demolish any justification for the series of murders perpetrated by the Bushveldt Carbineer officers, they are unlikely to change the popular perception.

(Walker, p. 17)

How it happened

What I see in this particular instance is an audience enamoured with certain ideals and as a consequence very receptive to any suggestion that a person might flesh out those ideals with his “real life” experiences. Of course there must be a mediator between those national or communal ideals in the minds and hopes of an audience, and the figure who might epitomize them. That mediator is the literary specialist whether the reporter or the acquaintance (i.e., Witton).

If we who are reading this post are also curious about the origin stories of Jesus we might wonder what principles we might pick up. From the above episode I would expect a historical person to become a mythical hero IF and WHEN the mythic ideals are already well established in the minds and hearts of the readership. That would be an essential sine qua non.

Once that essential condition is established one has no reason at all to think that there might be any embarrassment attached to anyone who could be reimagined (playing up certain characteristics, downplaying or ignoring others) as stepping in to and emerging idealistically from that mold.

This post presents but one instance of a scapegrace emerging as a national mythic hero. I do not claim it speaks for all.

Walker, Shirley. 1985. “‘A Man Never Knows His Luck in South Africa’: Some Australian Literary Myths from the Boer War.” English in Africa 12 (2): 1–20.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Great analogy.

The barbaric, immoral behavior of the British in the Boer War is rarely mentioned. They rounded up the wives and children of the Boer soldiers and placed them in concentration camps where they died of disease in the thousands. The Germans committed similar crimes in WWII, admittedly in larger numbers, but at least the Germans have admitted their crimes, apologized, and provided restitution. We are still waiting for the British to do the same.

A new book look at these developments in a wider context: Barbed-Wire Imperialism: Britain’s Empire of Camps, 1876-1903

I believe the Camps were run more efficiently (less brutally) after they brought over administrators from India who had experience running large camps. Whereas Nazi camps became even worse as the years passed.

Can the Anglophobia. We never explicitly set out to harm, let alone commit genocide, as the Germans did on multiple occasions; neither are they my crimes, nor those of any of my contemporaries. We have nothing to apologise for; certainly not to a people, the Boers, who base their whole culture on racism.

Surely you are being sarcastic. Please tell me you are joking.

It is interesting to consider the role of war in the emergence of myths. I hadn’t really thought about it in a larger context, but thinking about it now, so many myths and mythic heroes come out of war. Thus, it should be no surprise that the First Jewish-Roman War played such a role in the rise of the Jesus myth.

If you recall the passages in Chapter 4 of my book, from Eusebius, Martyr, and Lactantius, it clearly shows how the pump had been primed for them (and the whole Roman culture) to accept the Jesus of the Gospels as the evidence that their treatment of the Jewish people was appropriate and divinely ordained.

And also, when thinking about how these types of misconceptions arise, as you note with this case and others, these types of things even happen today, so just imagine how easy these types of misconceptions would have been 2,000 years ago. I mean, it’s a reasonable misunderstanding for the time, especially in light of the fact that similar types of misunderstandings still happen even now.

On another literary note, I like to compare the Gospel of Mark to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Indeed I think Huckleberry Finn and GMark share many similarities in style and purpose.

Finn was published in 1885, shortly after the American Civil War. The story, however, is set in roughly the 1850s, shortly before the Civil War. The story is pseudo-historical, i.e. it follows fictional characters in a real historical setting. The story essentially follows the escape of the slave boy Jim as he flees the South. Along this journey Huck and Jim have many encounters with various Southerners who are portrayed as rascals, liars, thieves, fools, etc. So the story, written after the war, presents the Southerners as a bunch of bad people who deserved what the entire audience knew befell them.

So I see this as really the exact same type of story as GMark, and while this didn’t happen in this case, it’s easy to see how characters like Jim and Finn could be mistakenly historicized.

RG Price – the date of setting of Huck Finn is usually given as 1835-45 (Twain said it was 40-50 years before book’s publication). Jim is a grown man with children. He weeps remembering how he misjudged his deaf daughter, e.g. Not all the Southerners are rascals. Some suffer from the same warped conscience as Huck, such as Judith Loftus, who is glad there were no injuries in the explosion on shore (other than a black person who was killed). Twain shows how ordinary people with basically good hearts can believe in the rectitude of slavery through cultural (including religious) indoctrination. Huck must decide to go to hell in order to help Jim escape slavery. The view that the story “presents Southerners as a bunch of bad people who deserved what the entire audience knew befell them” turns the novel into a self-righteous tract, something it is most definitely not. Jim and Finn have never been mistakenly historicized, to my knowledge. The novel is certainly not “the exact same type of story as GMark.” Just my opinion.

I wasn’t saying that they were historicized, but that I could see how it could happen from such a story. And honestly, I haven’t read Huck Finn since high school, I’m just drawing on my memories of it, but that’s how it seemed to me. And regardless of Twain’s intent, it remains that the Southerners were portrayed poorly overall, and this fit with the climate of the time. It was okay to portray them as such because it fit with the expectations of the losers of the Civil War. Put it this way: If the South had won the Civil War would Huck Finn have been written? I think that’s an easy NO. But see, Christians don’t seem to realize this about GMark, i.e. that if not for the Jewish-Roman War it would not have been written. I think the answer regarding GMark is just the same as Huck Finn. Without the Civil War Huck Finn wouldn’t have been written and without the First Jewish-Roman War GMark wouldn’t have been.

But yeah, perhaps “exact same type of story” was an overstep. Huck Finn is, at the very least, a very similar type of story to GMark IMO. Both are postwar narratives built on postwar views, set in prewar times, that portray prewar circumstances through a postwar lens.