(Part 1 can be found here: McGrath’s BI Review of Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus, 1)

McGrath begins his second attempted substantive criticism of Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus with the following mischievous introduction:

It is obviously very easy to find parallels when one’s standard for positing one text having inspired another is that there be prepositions in both, and when something being different (such as gender) can simply be treated as a deliberate reversal.

Of course none of the many peer-reviewed scholarly arguments for reading ancient texts (both classical and biblical) intertextually and mimetically posit a standard “that there be prepositions in both” or “something different . . . can simply be treated as a deliberate reversal.” Nothing in the example McGrath quotes from Carrier supports the suggestion that Carrier is playing fast and loose with superficial rationalizations of counterintuitive similarities. Scholarly criteria for the sort of reading Carrier is undertaking abound: for some of these see 3 Criteria Lists and the several citations in Deeps Below, Storms Ahead.

Without any explanation of Carrier’s overall argument in any of his Bible and Interpretation “reviews” (one normally expects to find an explanation of the overall argument of a work any scholarly review) and without any explanation of where Carrier’s discussion of the Gospel of Mark fits in his larger thesis, McGrath proceeds to quote one portion of Carrier’s discussion of Mark’s use of narratives from Exodus:

Moses performs two water miracles that end the people’s thirst: the tree revealed by God (making bitter water drinkable again, his second miracle), and the flow of water struck from a rock (his fourth miracle). Mark has split these up, so that each inspires two miracle narratives for Jesus, but in different sequences, thus keeping the total miracle narratives in each sequence at five yet another conspicuous coincidence, evincing considerable artifice. In the first sequence Mark draws on the water from a rock episode, which carried the theme of faith overcoming fear and thus obtaining salvation. Hence, the episodes of Jairus’s daughter and the woman with a hemorrhage have the same theme of faith overcoming fear to achieve salvation from suffering or death. The woman also flowed with blood, while the rock flowed with water. And in the Jairus narrative Jesus takes only his top three apostles with him into the bed chamber (the pillars Peter, James and John: Mk 5.37), just as Moses is told to take only three elders with him to strike the rock (Exod. 17.5). The Exodus narrative likewise has the Jews perishing and worried about dying (17.3), thus Mark produces parallel narratives about a woman perishing (besides the obvious fact that she was slowly bleeding to death, that her condition was worsening is explicitly stated: Mk 5.26) and a girl who died.

Oblivious to the context of the above passage and forgetful of all other scholarship relating to textual and thematic links between the Gospel and Pentateuch McGrath responds with a rhetorical question:

Did the woman’s flow of blood remind you of Moses and the water flowing from the rock?

Of course not. But one expects a scholar to explain the context and argument of a work he is criticizing and McGrath has failed to do that here. He has given readers no indication at all of the context or point of Carrier’s passage.

To begin with Carrier acknowledged that his interpretation arose out of the work of Paul Achtemeier:

For the following, I’m adopting some of the analysis (but not all of the conclusions) of Paul Achtemeier in ‘Toward the Isolation of Pre-Markan Miracle Catenae’, Journal of Biblical Literature 89 (September 1970), pp. 265-91; and Paul Achtemeier, ‘The Origin and Function of the Pre-Marcan Miracle Catenae’, Journal of Biblical Literature 91 (June 1972), pp. 198-221

Achtemeier identified an intertextual link between a group of five miracles in the Gospel of Mark with a set of five miracles in the Book of Exodus. The Gospel’s group begin with a sea miracle (Jesus commanding chaotic weather and waves to be calm) at Mark 4:35-41 and end with a miraculous feeding of 5000 at Mark 6:34-44, 53. The Moses story from Exodus 13 to 17 begins with the command for the sea to allow safe passage for the Israelites and ends with the miraculous feeding of the multitudes in the wilderness. Achtemeier did not identify any intertextual links between the middle three miracles in Exodus and those in Mark — except for the simple fact of three miracles.

But Achtemeier did refer to the works of other reputable scholars who noticed that the same passage in the Gospel of Mark appears to draw upon other passages in Exodus, Numbers and Isaiah.

McGrath might object: Did the scene of Jesus miraculously feeding 5000 remind you of Moses pasturing Raguel’s flock in Exodus 3, or of Moses’ administrative organization of the tribes of Israel, or of Moses asking God to provide a new leader for Israel after his death as in Numbers 27? Would McGrath really be so flippantly dismissive of the arguments of scholars like Paul Achtemeier, Wayne Meeks, F. Hahn, G. Friedrich, H. Montefiore?

Achtemeier (1972)

A prime example of the influence of the Moses tradition is to be seen in the account of the wondrous feeding, with which the catenae conclude. The manna miracle held great interest for hellenistic Judaism,26 so it is not surprising that reflections of the Moses tradition are to be seen especially in the account of the feeding of the 5,000.27

Mark 6:34a may be a reference to Num 27:16-18, with its leaderless masses;28 the “green grass” of vs. 39 may be an eschatological blooming of the desert as the “one like Moses” repeats the manna miracle;29 the division into 100’s and 50’s in vs. 40 may reflect the ordering of Israel in Exod 18:13-27.30. Persuasive arguments can also be marshalled in favor of the thesis that John’s account of this event has been deliberately shaped in the light of Moses and the wilderness tradition.31

The event with which the catenae end seems thus to have been shaped against the background of a Moses tradition. In view of the order of events which constitute the catenae, it is of further interest to note that the two major miracles associated with the exodus-passing through the sea and the wondrous feeding in the desert-comprise the kind of miracle with which the catenae begin and end, viz., a sea-miracle and a feeding-miracle.32

—

26 See Kertelge, Die Wunder Jesu,134, n. 545.

27 Hahn, Hoheitstitel, 391.

28 So H. Montefiore, “Revolt in the Desert?” NTS 8 (1961-62) 135-41, esp. p. 136; and G. Friedrich, “Die beiden Erzihlungen von der Speisung in Mark 6:31-44; 8:1-9,” TZ 20 (1964) 10-22, esp. p. 19. However, B. van Iersel (“Die wunderbare Speisung und das Abendmahl in der synoptischen Tradition,” NovT 7 [1964-65] 167-94) argues against such an association (esp. p. 188).

29 So G. Friedrich (“Die beiden Erzihlungen,” 18ff.), again disputed by van Iersel (“Die wunderbare Speisung,” 188).

30 G. Friedrich, “Die beiden Erzahlungen, 17-18; see also Kertelge, Die Wunder Jesu, 133.

31 Cf. Meeks The Prophet-King, 98; E. Stauffer,” Antike Jesustradition and Jesuspolemik im mittelalterlichen Orient,” ZNW 46 (1955) 2-30, esp. p. 29.

32 Five miracles are reported from Egypt to Sinai in Exodus 13-17, but they are of somewhat different content than those in the cantenae–there are no healings in the Exodus accounts–so that the sheer fact of five miracles in the wilderness account and in the catenae does not indicate any clear relationship.

Meeks, p. 97 The Prophet-King (1967)

It is worth noting that the phrase “like sheep with no shepherd” is found already connected with the feeding narrative in Mark 6.34.3 Apparently the oral tradition of some segments of the early church identified the feeding of the multitude as the act of the shepherd who was to gather Israel.4

—

3 Perhaps derived from Num. 27.17. Neither Lk. nor Mt. follows Mk., but Mt. uses the verse in 9.36 where he adds ήσαν έσκυλμένοι και έριμμένοι. The latter may have been suggested by the נפצים of 1 Kings 22.17; the rest of the quotation follows Mk. 6.34.

4 The apparently irrelevant reference to the “plentiful grass” (Jn. 6.10; cf. Mk. 6.39) may also be a subtle allusion to the Good Shepherd’s care for the sheep. Cf. Philo, Mos. I, 65; Josephus, Antt. ii, 264f., on luxuriant grass on Sinai, where Moses pastured Raguel’s flock. This tradition is also known in haggadah; see Salomo Rappaport, Agada und Exegese bei Flavius Josephus (Frankfort a/M: J. Kauffmann Verlag, 1930), pp. 29, 117f., n. 144.

If the evangelist was framing a part of his gospel around the five miracles between the Red Sea and the miracle of manna as is indicated by the both sets of five miracles beginning and ending with thematically similar wonders, then we would expect there to be some textual and/or thematic links between the other miracles in the same set. It’s a classic case of a hypothesis being proposed (Mark draws upon the five miracles in Exodus) and testing that hypothesis with a prediction. Carrier identifies the textual and thematic links in the miracles in between the sea miracles and the miraculous feedings.

McGrath has misrepresented Carrier’s argument by claiming he is engaging in uncontrolled and even fantastic (certainly unscholarly) speculation.

Worse yet, McGrath appears even to be denying that in the Gospel of Mark the author has deliberately framed a second set of five miracles to match the earlier five despite such an observation being a commonplace in the scholarly literature on the Gospel of Mark:

| Mark 4:35-6:44 | Mark 6:45-8:26 |

| Stilling the Storm (4:35-41) | Walking on the Sea (6:45-51) |

| Exorcism of a Gentile Man – Gerasene (5:1-20) | Exorcism of a Gentile Woman – Syrophoenician (7:24-30) |

| Curing older woman – hemorrhage (5:25-34) | Curing deaf-mute man with spit (7:32-37) |

| Curing younger woman – Jairus’ daughter (5:21-23; 35-43) | Miraculous feeding – 4000 (8:1-10) |

| Miraculous feeding – 5000 (6:34-44) | Curing blind man with spit (8:22-29) |

As we saw above, McGrath apparently even mocks the idea that there are real parallels here because one has to somehow resort to what he suggests is tendentious nonsense like suggesting that the author has “deliberately reversed” the the genders of those healed:

It is obviously very easy to find parallels when one’s standard for positing one text having inspired another is that there be prepositions in both, and when something being different (such as gender) can simply be treated as a deliberate reversal.

By this logic we would be forced to deny that even the two miraculous feedings bore any genetic relationship with each other because the numbers differed.

Parallelophobia?

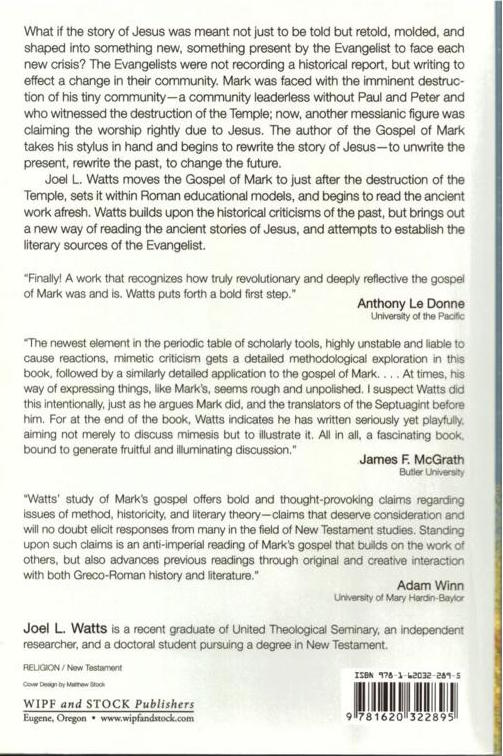

On the other hand, Dr McGrath’s wrote a commendation for a book by his blogger friend, Joel Watts, titled Mimetic Criticism and the Gospel of Mark: An Introduction and Commentary (2013). On the back cover of that book we read these words by James F. McGrath:

The newest element in the periodic table of scholarly tools . . . . bound to generate fruitful and illuminating discussion

But even here McGrath did express some reservation, adding that this “newest element” was “highly unstable and liable to cause reactions”. And wisely in this case, too. Here is an example of the sort of parallelism one finds in Watts’s book and that McGrath presented as a potentially fruitful scholarly tool (p. 124):

| 2 Kings 5-6 | Mark 2:1-18 |

| Israel Occupied | Israel Occupied |

| Cannibalism | Jesus calls the tax collector |

| Windows of Heaven (actually in 2 Kings 7, not 5-6) | Four men open windows of heaven (Mark 2:3-4) |

| Elisha in his house hides from the murder (sic) | Jesus welcomes sinners and tax collectors |

| Four lepers announce God’s victory | Jesus heals the sick |

For the benefit of any readers wondering what connection exists between cannibalism and Jesus calling the tax collector Watts helpfully clarifies:

Levi was a Jew feeding off his family, just as the scenes of cannibalism mentioned in the 2 Kings 6.28-30. (sic)

That’s how McGrath and other scholars respond to a truly incompetent bit of nonsense pretending to be mimetic criticism when it is published by one of their own ideological companions.

.

The time it has taken for me produce this post is to some extent a measure of how tedious I have come to find McGrath’s unprofessional (let’s say less than fully honest) attacks on anything written by a mythicist. I did not believe that the depths to which he resorted in his blatant misrepresentations of Doherty’s book would be repeated in a peer-reviewed article. That peers chose to approve obviously distorted and fallacious criticism of Carrier’s peer-reviewed book demonstrates, I think, that the debate is not about scholarly argument but ideology.

Before I finished this post Richard Carrier has posted his own response to McGrath’s review. I have yet to read it but no doubt it will be a more comprehensive response. (McGrath has since replied with a counter-accusation of dishonesty and his own inability to handle criticism of his own published assertions and respond with reasoned argument and by falsely suggesting that Carrier is criticising honest argument; his justification is that he himself, James McGrath, also treats certain biblical passages as symbolic to parallel Jesus with Moses – yet without explaining how Carrier’s and other scholarly studies along these lines are any different. As for honesty, McGrath stretches the standard to requiring anyone to first seek his permission before quoting any words he has posted in a public forum. )

I had also planned to include here a list of scholarly works undertaking the same kind of intertextual studies that McGrath criticizes in Carrier. Perhaps I can take the time to do that another day but I do want to at least mention a few here (and who are far more competent at such analysis than Watts):

- The New Moses : a Matthean typology by Dale C. Allison

- Reading the Bible Intertextually by Richard B. Hays, Stefan Alkier, Leroy Andrew Huizenga

- The Way of the Lord: Christological Exegesis on the Old Testament in the Gospel of Mark by Joel Marcus

- Isaiah’s New Exodus in Mark by Rikki E. Watts (not to be confused with Joel Watts)

- Mark and the Elijah-Elisha narrative : considering the practice of Greco-Roman imitation in the search for Markan source material by Adam Winn

- The Function of Scriptural Quotations and Allusions in Mark 11-16 by Howard Clarke Kee

- The Open Tomb : a new approach, Mark’s Passover Haggadah by Karel Hanhart

- The Jewish Gospels: The Story of the Jewish Christ by Daniel Boyarin

- The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son by Jon D. Levenson

- Sowing the Gospel by Mary Ann Tolbert

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It is indeed remarkable that the central event of the religion (The Passion of the Christ in Mark) utterly lacks any historical memory attached to it, and is instead recreated (or created?) using silent allusions to lines in the Psalms, Isaiah, and the Wisdom of Solomon. This makes great theological literature, for sure, but history? I tend to doubt it.

Consider: The Passion of the Christ in Mark:

Likely the clearest Prophecy about Jesus is the entire 53rd chapter of Isaiah. Isaiah 53:3-7 is especially unmistakable: “He was despised and rejected by men, a man of sorrows, and familiar with suffering. Like one from whom men hide their faces he was despised, and we esteemed him not. Surely he took up our infirmities and carried our sorrows, yet we considered him stricken by God, smitten by him, and afflicted. But he was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities; the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we are healed. We all, like sheep, have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own way; and the LORD has laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed and afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; he was led like a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth.”

The only thing is, as Spong points out, Isaiah wasn’t making a prophesy aboout Jesus. Mark was doing a haggadic midrash on Isaiah. So, Mark depicts Jesus as one who is despised and rejected, a man of sorrow acquainted with grief. He then describes Jesus as wounded for our transgressions, bruised for our iniquities. The Servant in Isaiah, like Jesus in Mark, is silent before his accusers. In Isaiah it says of the servant with his stripes we are healed, which Mark turned into the story of the scourging of Jesus. This is, in part, is where atonement theology comes from, but it would be silly to say II Isaiah was talking about atonement. The servant is numbered among the transgressors in Isaiah, so Jesus is crucified between two thieves. The Isaiah servant would make his grave with the rich, So Jesus is buried in the tomb of Joseph of Arimathea, a person of means.

Then, as Dr. Robert Price says

The substructure for the crucifixion in chapter 15 is, as all recognize, Psalm 22, from which derive all the major details, including the implicit piercing of hands and feet (Mark 24//Psalm 22:16b), the dividing of his garments and casting lots for them (Mark 15:24//Psalm 22:18), the “wagging heads” of the mockers (Mark 15:20//Psalm 22:7), and of course the cry of dereliction, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34//Psalm 22:1). Matthew adds another quote, “He trusts in God. Let God deliver him now if he desires him” (Matthew 7:43//Psalm 22:8), as well as a strong allusion (“for he said, ‘I am the son of God’” 27:43b) to Wisdom of Solomon 2:12-20, which underlies the whole story anyway (Miller, p. 362), “Let us lie in wait for the righteous man because he is inconvenient to us and opposes our actions; he reproaches us for sins against the law and accuses us of sins against our training. He professes to have knowledge of God, and calls himself a child of the Lord. He became to us a reproof of our thoughts; the very sight of him is a burden to us because his manner of life is unlike that of others, and his ways are strange. We are considered by him as something base, and he avoids our ways as unclean; he calls the last end of the righteous happy, and boasts that God is his father. Let us see if his words are true, and let us test what will happen at the end of his life: for if the righteous man is God’s son he will help him and will deliver him from the hand of his

adversaries. Let us test him with insult and torture that we may find out how gentle he is and make trial of his forbearance. Let us condemn him to a shameful death, for, according to what he says, he will be protected.”

As for other details, Crossan (p. 198) points out that the darkness at noon comes from Amos 8:9, while the vinegar and gall come from Psalm 69:21. It is remarkable that Mark does anything but call attention to the scriptural basis for the crucifixion account. There is nothing said of scripture being fulfilled here. It is all simply presented as the events of Jesus’ execution. It is we who must ferret out the real sources of the story. This is quite different, e.g., in John, where explicit scripture citations are given, e.g., for Jesus’ legs not being broken to hasten his death (John 19:36), either Exodus 12:10, Numbers 9:12, or Psalm 34:19-20 (Crossan, p. 168). Whence did Mark derive the tearing asunder of the Temple veil, from top to bottom (Mark 15:38)? Perhaps from the death of Hector in the Iliad (MacDonald, pp. 144-145). Hector dies forsaken by Zeus. The women of Troy watched from afar off (as the Galilean women do in Mark 15:40), and the whole of Troy mourned as if their city had already been destroyed “from top to bottom,” just as the ripping of the veil seems to be a portent of Jerusalem’s eventual doom.

And so we can at least propose there may not be any historical content with a fairly comprehensive haggadic midrash reading of The Passion of the Christ in Mark.

I think Matthew 27:43 comes from Wisdom of Solomon 22:18, which comes from Psalm 22:8. It is the beginning of WoS 22:18, “for if the righteous man is God’s child”, alignment with “I am the son of God” that convinces me.

Might Mark 15:38 also come from Zechariah 14:4 about the Mount of Olives being torn asunder? Mark often combines something from the Greek literature with a dressing of Hebrew scripture. Matthew 27:51, about the earthquake and rock splitting, likely comes from Zechariah 14:4-5.

I wonder if the veil has anything to do with this?

Since the crucifixion in Mark is the central event of the religion, it would be interesting if Vridar would do a full post about why the crucifixion in Mark is fiction.

Not the same thing but worth thinking about: Jewish Scriptures in Mark’s Passion and Resurrection Narrative.

What I personally find of most significance (though it won’t have the same impact for everyone) is that the earliest references to the crucifixion are never historical, they are never “reports” or “accounts” of a news type or biographical event. They are always theological statements. They are not even about a normal human but about a divinity. And the crucifixion in these theological claims has no significance or meaning without the resurrection.

Prima facie there is simply no historical question to investigate. It is an entirely theological claim about a divinity and a miracle that come together to change the religious status of believers.

I noticed on the comments on your link that you were still on speaking terms with McGrath at the time.

That was the fourth comment McGrath posted to Vridar. The previous three were:

http://vridar.org/2008/08/11/israels-second-god-2-and-a-bit/#comment-1549

http://vridar.org/2008/05/26/how-polytheism-morphed-into-monotheism-philosophical-moves-2/#comment-1415

and the very first was in March 2008:

http://vridar.org/2008/03/11/a-parable-of-the-pounds-thought-experiment/#comment-1242

He clearly indicated his respect for my knowledge and arguments back then when he decided to make himself known to me.

Hi Neil,

I think I have found a possible midrashic source for Luke’s explicit count of three attempts by Pilate to save Jesus.

I read this in The Power of Parable, of J.D. Crossan:

Once again I begin with Jesus in Luke’s first volume. Jesus’s only confrontation with direct Roman authority is in his trial before Pilate. All the gospel writers have Pilate declare Jesus innocent, but Luke, and only Luke, has Pilate insist three times that Jesus is free of any crime. Luke even counts out Pilate’s declarations of Jesus’s innocence, in case you might miss that emphasis:

[1] Pilate said to the chief priests and the crowds, “I find no basis for an accusation against this man.” (23:4)

[2] Pilate…said to them, “You brought me this man as one who was perverting the people;

and here I have examined him in your presence and have not found this man guilty of any of your charges against him. Neither has Herod, for he sent him back to us. Indeed, he has done nothing to deserve death.” (23:13–15)

[3] A third time Pilate said to them, “Why, what evil has he done? I have found in him no ground for the sentence of death.” (23:22)

Note that explicit count of “a third time.” Furthermore, Luke, and only Luke, has Jesus appear before both Pilate and Antipas.

So Josephus, Antiquities 18:55-60 :

But now Pilate, the procurator of Judea, removed the army from Cesarea to Jerusalem, to take their winter quarters there, in order to abolish the Jewish laws. So he introduced Caesar’s effigies, which were upon the ensigns, and brought them into the city; whereas our law forbids us the very making of images; on which account the former procurators were wont to make their entry into the city with such ensigns as had not those ornaments. (1) Pilate was the first who brought those images to Jerusalem, and set them up there; which was done without the knowledge of the people, because it was done in the night time; but as soon as they knew it, they came in multitudes to Cesarea, and interceded with Pilate many days that he would remove the images; (2) and when he would not grant their requests, because it would tend to the injury of Caesar, while yet they persevered in their request, on the sixth day he ordered his soldiers to have their weapons privately, while he came and sat upon his judgment-seat, which seat was so prepared in the open place of the city, that it concealed the army that lay ready to oppress them; and when the Jews petitioned him again, (3) he gave a signal to the soldiers to encompass them routed, and threatened that their punishment should be no less than immediate death, unless they would leave off disturbing him, and go their ways home. But they threw themselves upon the ground, and laid their necks bare, and said they would take their death very willingly, rather than the wisdom of their laws should be transgressed; upon which Pilate was deeply affected with their firm resolution to keep their laws inviolable, and presently commanded the images to be carried back from Jerusalem to Cesarea.

I find some matches, in the same order.

1) Pilate that in Josephus introduces symbols of a foreign religion by night to show them to Jews at day (as a true conspirator) becomes in Luke the Sanhedrin who conspires against Jesus by night presenting him to Pilate at day.

2) Pilate that appeals to the emperor in Josephus becomes in Luke Pilate that appeals to Herod, in both cases without success.

3) Pilate that in Josephus exhibits the threat of physical violence (as extrema ratio), becomes in Luke the same Pilate the wants to persuade Jews showing them the real risk that, if Jesus should be crucified, then the violent Barabbas will be free in his place.

My opinion is that the episode about Pontius Pilate’s insignia was used as midrashical source by Luke because, in that episode of Josephus, Pilate was a perfect example of a Roman governor who had succumbed to the insistence of the Jews of Jerusalem about the introduction of so-called symbols of foreign ”gods”.

But as the episode of the busts of emperors told by Josephus is a credit to the insistence of the Jews in their tenacious protest to Pilate (as proof of their loyalty to their traditions and laws), the point of the evangelist is exactly antithetical to that of Josephus : being forced by their laws and traditions (definitively not divine) the Jews insist before Pilate not for a good cause (as it could be rejecting the idolatrous images of the emperors) but for an unjust cause (condemn to death the Son of God).

It cannot be a coincidence that only in the Gospel of Luke and in Josephus it is found a Roman governor (named just Pilate!) who succumbs at the insistence of the Jews, despite having appealed before to a superior and then to the threat of physical violence, regarding the introduction of symbol of foreign religion.

IF it’s a mere coincidence and parallelomania, I would like to know if this answer would be like saying that it was only ”for a mere, very rare coincidence” that Philo named ”Jesus” his Logos attributing him the same characteristics of the Jesus of Paul. Contra all the reasons given by Richard Carrier to think otherwise.

Honestly, Neil, do you think I’m suffering from ”parallelomania” when I claim that Luke is deriving from Josephus in his description of the Roman trial of Jesus?

I’m open to criticism and reproaches, because I realize that if I was right, in the light of the fact that the proto-Luke has a good chance of being the first gospel, then this midrash from Josephus about Pilate implies that Pilate was introduced in the gospel only for one exquisitely theological/midrashical reason (and not because Jesus had to be set in the context of time, not even because Pilate crucified the historical Jesus).

Very thanks and I apologize for the length of the comment if you did lose too much time to read it.

Giuseppe

John 19 also has Pilate trying to release Jesus three times.

4] Then Pilate went out again, and said to them, “Behold, I bring him out to you, that you may know that I find no basis for a charge against him.”

6b] Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves, and crucify him, for I find no basis for a charge against him.”

12] At this, Pilate was seeking to release him, but the Jews cried out, saying, “If you release this man, you aren’t Caesar’s friend! Everyone who makes himself a king speaks against Caesar!”

Luke 23:4

I find g2147 εὑρίσκω heuriskō

no g3762 οὐδείς oudeis

fault g158 αἴτιον aition

in g1722 ἐν en

this g5129 τούτῳ toutō

man. g444 ἄνθρωπος anthrōpos

John 19:4

I find g2147 εὑρίσκω heuriskō

no g3762 οὐδείς oudeis

fault g156 αἰτία aitia

in g1722 ἐν en

him. g846 αὐτός autos

According to McGrathian logic, it is perfectly fine to cite parallels between the Old and New Testaments, even if it is only a gender switch, as long as such citation comes from someone inside the Jesus Academy who (of course) affirms the historicity of Jesus.

b/c Christians believe that God was outlining his plans with the OT.

They think the OT is prospective, rather than the NT being a redacted re-telling of the OT, with human sacrifice as the new theology.