Richard Horsley has produced a couple of books I have found far more enlightening than his earlier work on bandits and prophets in first-century Judea. One of these is Scribes, Visionaries and the Politics of Second Temple Judea from 2007; the other, The Prophet Jesus and the Renewal of Israel, 2012. One of several points that has hit me already from these two works is a deeper appreciation of the literary way the Gospels convey the sayings of Jesus.

Take the Sermon on the Mount. I think we all know that Jesus could not really have stood up and pronounced a long list of aphorisms the way Matthew depicts. So we hear the more learned ones explaining to us that Matthew was recording a summary of the sorts of things Jesus often said.

But stop and think for a minute. Aren’t the evangelists (authors of the gospels) supposed to be writing something akin to a history or biography? And weren’t ancient historians known for the way they would construct speeches they believed were “true to life” or “appropriate” or “realistic” in the mouth of certain historical characters? But that’s not what we read in the gospels when it comes to the speeches of Jesus. Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount and Luke’s Sermon on the Plain are anything but reconstructed “speeches”.

Rather, they read like a chapter or so from the Book of Proverbs. Not like speeches. Jesus is not “preaching” about forgiveness and an appropriate speech is not constructed for any such message. Jesus simply delivers a proverb or saying or edict, brief enough to be remembered and recorded in a list of one-liners. It’s not unlike the way he is portrayed as speaking in the Gospel of Thomas when he drops line after line of mystery saying.

The evangelists — at least the Synoptic ones (Matthew, Mark and Luke) — are not even trying to reconstruct speeches of Jesus.

They are writing a set of one-liner sayings.

Okay, but what is the problem with this? Horsley puts his finger on it exactly:

Focus on individual sayings . . . tends to reify them as statements or principles or precious nuggets of wisdom abstracted from the contingencies of historical life. Tellingly, standard study of the historical Jesus is specially concerned about the transmission of particular sayings, as if they were precious objects being “handed (down)” from one person to another. The resulting picture of Jesus is as a revealer who, unengaged with concrete historical life, utters one-liners. To have become a historically significant figure, Jesus must have communicated with people, particularly his followers. But it is difficult to imagine that anyone could communicate merely in individual sayings. (p.2, Kindle version, my bolding)

Here it is again, this time perhaps more direct:

Jesus (or anyone else), however, could not have communicated by means of individual “sayings,” which are later abstractions from speeches or “pronouncement” stories, etc., and hence cannot be the sources for the historical Jesus.(p. 153)

It is really beyond anyone’s ability to uncover actual words spoken by Jesus.

What this leaves us with is a requirement to appreciate the gospels as literary wholes. I think if we read a list of sayings as in the Sermon on the Mount what we are reading is a literary presentation of Jesus as a teacher of wisdom (like Solomon) or edicts (like Moses).

Even if we read a one-liner isolated from other sayings, as when Jesus blesses those who leave all their goods to follow him (Mark 10:29-31) we are still reading a proverb-mouthpiece in a narrative context. We are hardly reading the words of someone who was able to eloquently persuade people to leave all and follow him.

Who knows if such sayings are indeed summaries of various ideas expressed by such a Jesus? I’m not suggesting that an appreciation for the implications of the one-liner Jesus we read of in the gospels means these sorts of things were not said by the real Jesus. But as Horsley says, no-one could engage with people or command a dedicated following by talking like that. And if he did not talk like that, then it is pointless to ask if such gospels sayings were really spoken by Jesus.

The sources of the sayings put into Jesus’ mouth are another question.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

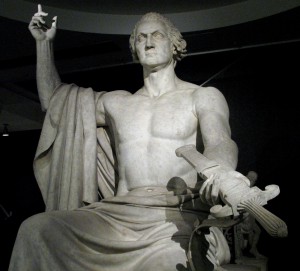

Check out a picture of the statue of Geo. Washington by Horatio Greenough.

In my teenage years, this would be the image I would conjure when reading about the “proclamation” Jesus of the gospel narratives ~~ anything but the warm intimate individual with whom evangelicals advise the newly faithful should cultivate a personal relationship. Jesus seldom even converses to His disciples. He “proclaims” to(at) them.

Thanks for a great post, revealing true literary import.

Perfect illustration for the post. Thanks. Have added it now.

So many problems appear when you take the Sunday School blinders off. McGrath, and many others, just can’t seem to do that. See this post and his response to my question at the bottom of the thread. http://www.patheos.com/blogs/exploringourmatrix/2014/03/the-path-to-discerning-gods-will.html#comment-1311655262

Btw, Frank Schafer (Francis’ son) has a great interview at the Point of Inquiry podcast (CFI).

Can you give us a link to the podcast? (We non-Americans don’t know who the Schafers are, either, sorry. Happy to learn, though.)

From another perspective — I had a look at McG’s post and was most shocked by the way several commentators thought it was so insightful — Sheesh, I thought it was quotidian. I couldn’t resist leaving the thought that the only reason the parable of the Good Samaritan has any so-called “wow” factor is because it tells the religiously minded to let go of their religion for a moment and just relate to fellow humanity like the social creatures we are by nature. I expect they’ll just think I’m a Satanist or something.

Was on my phone, so that’s all I could manage. The podcast only lightly touches Phelps btw.

http://www.pointofinquiry.org/frank_schaeffer_on_escaping_fundamentalism_and_the_death_of_fred_phelps/

Francis (was a leading evangelical) and Frank Schaeffer are fascinating people. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Schaeffer

http://www.frankschaeffer.com/

You’re forgiven. Thanks. 🙂

I’ve been giving some more consideration lately to Shem Tov’s Hebrew Matthew (in Howard’s book from 1995). This gospel is discussed in Nehemia Gordon’s book The Hebrew Yeshua vs. the Greek Matthew, where he shows that this Hebrew Matthew (regardless of its transmission history) makes more sense in certain cases than the Greek, and exhibits interesting wordplays and puns that are absent in the Greek.

I’m aware of the uncertainties regarding Hebrew versions of Matthew (and the ancient witnesses to such), and thus have viewed them with reserve over the years. But the more I think about the details in Gordon’s little book, the more I’m starting to wonder if there could be something historically useful about Shem Tov’s version after all. Not that I’m thinking that this is likely, just that it may be worth a little more thought.

Have you read Howard’s book or looked into the issue of the Hebrew Matthew?

No, I haven’t read any of these. Something I’ve since added to my already long list.

Niel, have you heard of Raphael Lataster? He’s a PhD student in religious studies and wrote his Masters thesis on Jesus Mythicism. I’m reading his book, There Was No Jesus, There Is No God which seems to sum up both his MA work and his current PhD work.

Yes, indeed. Raphael does know of this blog, too. I have corresponded with him a couple of times and we have met virtually face to face on a program recently arranged by Phil Robinson of Nuskeptix. He’s another academic who does publish in peer-review literature on Bayes and mythicism, if I recall correctly.

Sam brought up Washington, so I’ll bring up Abe Lincoln who said (with reference to the 1864 election), “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.” It’s one of my favorite Lincoln quotes — too bad he never said it.

As Sarah Silverman said, “There’s no B-side Jesus.” Now we know why. All we have are Jesus’ Greatest Hits.

The argument from Horsley seems too sweeping. When Jesus is “quoted” at length, as in “John”, his speeches are disregarded on other grounds. Some of the “one-liners” strike me as quotes sufficiently memorable, and sometimes sufficiently colorful or funny, to remain in the minds of listeners. In some cases what would have been parables or stories are given in summary form, whereas in reality they would have been longer, as is the case with preachers, politicians, teachers, comedians or writers at any other time in history. Of course, it could be – and is – argued that pithy remarks or proverbs have all just been purloined from actual rabbis or scriptures, and simply put in the mouth of one imaginary person.

Let me give an example from someone known for his eloquence, many public meetings and much “command and engagement with dedicated followers” – Oswald Mosley. His parliamentary speeches are clearly available, his fascist and especially post-war speeches less easily traceable, though some can be found in summary form. However, he is best remembered, if at all, for a few individual metaphors or striking quips, which I need not quote unless challenged; I doubt if many people, however, have the slightest accurate knowledge of the actual content of his postwar public speeches (or are acquainted with his half-a-dozen books or innumerable articles which are not relevant, of course, in comparison with Jesus). But one can detect similarities of theme, tone and manner, even sarcastic repartee, surprisingly enough, between the audience-gripping gospel Jesus and the modern Mosley. We live at a time when records are more abundant and accessible, but suppression of and distortion of the ideas of annoying mavericks, far from fictional, personalities still continue.

Hi David. Interesting point about what registers and is remembered. I agree that the arguments are often presented too simplistically or only with partial knowledge of the questions raised. This post does only cover one aspect of a much larger question.