Chapter 11

The Dominican Biblical Institute

.

This hurts. It becomes personal.

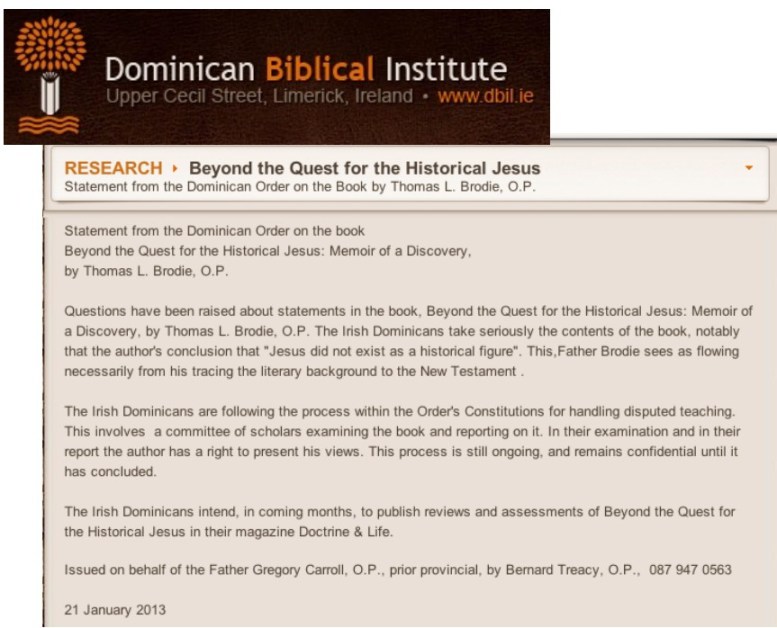

From my outsider perspective I understand that the Dominican Biblical Institute (DBI) was founded by Thomas Brodie (though he has an oblique way of explaining this in Beyond the Quest), so when I turn now to the DBI’s website to see what they have had to say about Brodie and the book, aspects of which I am addressing in this series of posts, and read the contents on the following images, it hurts, as it must hurt anyone who knows a significant loss that accompanies religious differences.

And so we come to chapter 11 of Beyond the Quest, in which Thomas Brodie gives an overview of plans, activities, a conference and research of the DBI.

It has three aims:

- Short-term: Immediate Service

- offering an accredited Diploma in Biblical and Theological Studies

- Lectio divina

- Public talks

- Medium /Long-term: Research that clarifies the roots (especially biblical roots) of the Catholic/Christian faith

- One way of doing this is by tracing how the texts were formed, something that gives clues to how the Church was formed, which in turn provides background that makes it easier to renew the church . . . . The two levels of engaging scripture, the intellectual quest to identify roots through research, and the spiritual quest to generate fresh life through exercises such as lectio, complement each other. . . (p. 104)

- Long-term: Help integrate Christianity with other truths

- The clarifying of Christian origins and Christian faith will make it easier to integrate the truth of faith appropriately with the truth that is in culture, art (including literature), world religions, and science. . . something cries out, not for uniformity — ‘vive la difference‘ at several levels — but for a reasonable amount of integration, harmony, and meaning. (p. 104)

Research

I omit here Thomas Brodie’s discussion on the Lectio Divina Conference, though I am sure it was of primary interest to him personally.

During the process of research in Limerick, the historical existence of Jesus was not discussed; it was taken for granted, and left undisturbed — probably the only practical way to proceed initially. As I see it, proposing Jesus did not exist historically is like a heart transplant; you either do it fully or not at all. Instead the research had other features and dealt with other topics. (p. 106)

Priority for literary issues, especially sources

So literary criticism has research priority. What the the text’s sources and what is the text’s artistic structure. Not that these are the primary end-goals of research, but they do need to be addressed and understood before other questions that derive from those texts.

The methods followed and developed, Brodie points out, have been “discussed and generally approved” by the Church in three main documents:

- 1893: Pope Leo XIII, Providentissimus Deus, emphasized the use of critical historical method

- 1943: Pope Pius XII, Divino Afflante-Spiritu, emphasized the need to identify literary form/nature

- 1993: Pope John Paul II/Pontifical Biblical Commission, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, identified five main kinds of methods, especially historical and literary. Joseph A. Fitzmyer has produced a useful commentary on this text.

The Old Testament/Hebrew Scriptures

Preliminary work has been done on “Genesis’ reshaping of the book of Jeremiah in the Jacob story”.

As for examining the re-working of Homer’s Odyssey in Genesis 11 to 50, this hoped-for study has not yet started.

But OT studies being done elsewhere “remain encouraging”

- Calum Carmichael, 1979, Women, Law, and the Genesis Traditions (on how Deuteronomy’s laws reshaped women-related episodes in Genesis)

- David P. Wright, 2009, Inventing God’s Law: How the Covenant Code of the Bible Used and Revised the Laws of Hammurabi

- Jeffrey Stackert, 2007, Rewriting the Torah

- Bernard Levinson, 1977, Deuteronomy and the Hermeneutics of Legal Innovation (I have posted in part on this book.)

The Gospels and Acts

DBI often uses as a starting point Thomas Brodie’s Birthing of the New Testament. The Intertextual Development of the New Testament Writings (2004). Brodie says of his conclusion (chapter 26) that he “certainly holds back”. Further,

I made the mistake too of including some examples that were weak (for instance, Chapter 52, on Judg. 21 and the Last Supper). I believe such examples are true, but they are indeed weak, and insistence on what is weak, whether by someone presenting the argument or someone opposing it, confuses the discussion. As in a courtroom, the issue is not whether some evidence is weak, but whether there is enough evidence that is strong. (p. 108)

Birthing is incomplete, Brodie says. It lacks a full discussion of the epistles. Nonetheless it goes further than any other work in providing a skeleton outline of how the NT documents were composed.

But the skeleton needs to be further tested and elaborated, and much of the work at the Limerick centre, while undertaken with an independent spirit, contributed to such testing or elaboration.

John Shelton and the centurion’s servant

One example of how testing and elaboration of Brodie’s ideas have led to revision of them came with John Shelton’s dissertation.

Brodie argued in Birthing that Luke’s account of the healing of the centurion’s servant — Luke 7:1-10 — depended upon Elijah’s saving of the widow’s children (in the LXX it is “children”, not “child”) — 1 Kings 17:1-16. John Shelton demonstrated an even stronger use of the healing of Naaman the Syrian commander (2 Kings 1-19).

So the relationship between the Gospel and Hebrew narrative was shown to be more complex than Brodie had initially thought. Moreover, it was more emphatically clear that the account in Luke did not come from Q but from the LXX.

The clarifying of the opening episode of Luke 7 (the centurion’s servant) serves in turn to bolster the already existing evidence that all three other episodes of Luke 7 — the raising of the widow’s son (7:11-17), the vindication of John the Baptist (7:18-35), and the woman’s anointing of Jesus’ feet (7:36-50) — likewise originated largely through Luke’s literary transformation of accounts from the Elijah-Elisha narrative.

Of these three, the one concerning John the Baptist is again an account that is usually attributed to the hypothetical Q. (p. 109, my formatting)

A primary result of Shelton’s work, then, has been to more strongly establish Luke’s indebtedness to the Elijah-Elisha narrative. By establishing Luke’s use of this narrative for material that has long been attributed to Q, Brodie is confident that we are entering

a line of inquiry that is more verifiable than invoking an unseen source that does not have so solid a literary foundation. Once Luke has been clarified through this more verifiable process, the way is open for a well-grounded discussion of Luke’s relationship to Matthew. (p. 109)

John’s transformation of the Synoptics

Anne O’Leary: showed Matthew’s reworking of Mark was done “in accordance with the literary practices of antiquity” (this half of her thesis was published in 2006) and that John in turn adapted sections of Matthew.

Martin Heffernan’s thesis on John 1-4 and Acts 1-8 showed Jesus journey from Jerusalem to Galilee corresponds strongly, and uniquely, to the apostolic journeys of Acts 1-8.

Clarifying Mark’s sources

The literary character of the Gospel of Mark “has slowly been appreciated”. It had long been considered unliterary, even clumsy, and its sources hopelessly lost. But the view of Mark as a literary work is gaining ground now, and two scholars who have made progress here are:

Adam Winn: showing in detail Mark’s indebtedness to the Elijah-Elisha narrative

Thomas Nelligan: uncovering evidence that the Gospel of Mark reflects Paul, especially in the case of 1 Corinthians where the associations are not just theological but also “precise and literary”.

Proto-Luke

This has not been investigated yet at DBI. The concept is of Septuagint-based version of Luke-Acts based on the Elijah-Elisha narrative. According to Brodie, such a document has potentially more explanatory power than Q, and promises clarification of the relationship between Matthew and Luke and provides a precedent for Mark, Matthew and John.

And it clarifies the reality behind Raymond Brown’s view (1971) that the Elijah-Elisha account is the best literary model for all four gospels. (p. 111)

Brodie has attempted to work with exponents of Q, believing a dialogue is more promising than an either-or conflict. Partly to promote such a dialogue a conference was held in 2008 devoted primarily to the role of the Elijah-Elisha narrative in the Gospels.

Paul’s epistles

In 2005 another conference attempted to explore the origin and nature and place of Paul’s letters. That is, it sought to address ways the epistles

- used older writings, especially the Jewish scriptures

- used one another

- were used by the evangelists

Results were published in The Intertextuality of the Epistles, edited by Brodie, MacDonald and Porter (2006). The CBQ review of this volume described it as “essays [that] herald a promising new approach”.

Brodie is especially keen on exploring in depth 1 Corinthians and its sources and final shape but this has yet to come to fruition.

Reflections

Thomas Brodie comes across as far more devout than many who shudder at his “mythicist” views would expect. I have posted on this before. He appears to have had no desire to thwart the spiritual growth of Christians but to establish it on a more deeply spiritual basis. One might even say that he has shown a way forward that was called for by the Protestant Albert Schweitzer

. . . Modern Christianity must always reckon with the possibility of having to abandon the historical figure of Jesus. Hence it must not artificially increase his importance by referring all theological knowledge to him and developing a ‘christocentric’ religion: the Lord may always be a mere element in ‘religion’, but he should never be considered its foundation.

To put it differently: religion must avail itself of a metaphysic, that is, a basic view of the nature and significance of being which is entirely independent of history and of knowledge transmitted from the past . . .

From pages 401-402 of The Quest of the Historical Jesus, 2001, by Albert Schweitzer.

The next section of Brodie’s Memoir is announced by the theme: Becoming aware of the need to lay some theories to rest. . . . .

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

This was a particularly odd chapter for me to read in the book as I spent 5 memorable years at the DBI and saw a lot of this work being carried out. Being part of this body work there was a real sense from those involved like we were doing something new and exciting. There was so much potential cut short by Tom’s departure from the centre. However, Gerard Norton was always a great friend to the DBI (in fact he donated much of the library from his own collection) and I am sure the DBI will get back on its feet.

Tom certainly put his heart and soul into the centre.

I’m sure many of us here would love to discuss those years over a dinner or a beer with you and others like you.

The title of Thomas Brodie’s book is “Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus”. A primary research goal of the DBI was to explore the origins of our canonical literature, and by implication, the origins of the Christian faith. That question must inevitably be prior to — “beyond” — a quest for the historical Jesus.

It has always been one of the purposes of this blog to look beyond the “quest for the historical Jesus” and to try to see what we can understand about the origins of the biblical literature and our religious heritage. This is what some critics have misunderstood when they have labelled this blog a “mythicist blog” and even complained because of my refusal to argue a clear case for a “mythical Jesus”. They fail to grasp that my interest is not in some quest for a mythical or historical or any Jesus at all. It is to explore what the evidence leads us to understand as the origins of it all. That question, as Brodie’s book title so aptly captures, is one that is “beyond” any such quest.

If and when a Jesus does emerge in the evidence, whether literary or historical (though how can any figure in literature not be literary!) then I do address such figures here.

The critics of this approach are, I fear, ideological in their objections, not methodological.