Continuing from Part 3 of this series. . . .

In the previous post we noted the impact of modern historical studies on the traditional view of the Bible as the reliable foundation of Christianity. The problem posed by modern (beginning especially in the nineteenth century) historical methods was that they left large portions of the Bible irrelevant. If God revealed himself in historical events that were the foundation of biblical narratives, and if we could not recover what those historical events really were, then we had a problem.

If the best solution was for scholars to read into biblical accounts “traits and motivations derived from contemporary culture”, then one had to conclude “the impossible”, that the Bible’s religious significance derived in large measure not from the Bible itself but from modern minds! Theoretically there could be as many different interpretations as there were interpreters.

If scientific historical methods were to be applied to the Bible (as many scholars were beginning to apply them in particular to the Old Testament), one had to assume that God did not literally intervene in human affairs to change the course of events.

The only message of the Bible that was left for scholars to pass on was that God was “benevolently disposed” towards the human species,

but nothing more substantial than signals of paternal affection and filial trust and obedience can get through [the window between God and the world to the eye of faith]. (p. 74, quoting T. W. Manson).

The third solution

So Bible scholars were able to bypass the challenge of the natural sciences with relative ease and to meet the challenge of modern historical methods by withdrawing to the bare minimum of what was required of their God to maintain any presence at all among the faithful. But that latter retreat left many of the devout unsatisfied. So there was what Dennis Nineham calls a “third movement”: one that showed God was not just a distant image but a dynamic force in world affairs. This was

a movement back to the Bible which shows God actively doing things in the world to guide history and save men, and offers authoritative interpretations of his actions instead of leaving each man to be his own interpreter. This movement sought to give full weight to its observation that in the Bible historical statements and theological interpretation go closely together. The typical biblical statement, it was argued, is logically of the form: ‘Such and such an event occurred, and it constituted a divine intervention in this world by which God’s redemptive work was carried forward in such and such a respect.’ (p. 74, my bolded emphasis)

We begin with arguably the most influential theologian of the twentieth century, Karl Barth.

Karl Barth

Karl Barth attracted widespread support around the time of the first world war when he expressed dissatisfaction with the view that Bible scholars were, in Nineham’s words, in

unnecessary bondage . . . to the canons of historical study. And that study itself . . . was in bondage to the prejudice that the course of events is always completely uniform, that nothing ever happens for the first time and that nothing can be allowed as having happened in the past of a kind which is not experienced as happening in the present. (p. 75)

In other words, theologians had fallen into bondage to the godless view that the course of battles or public movements can be explained entirely as having human and natural causes.

But that’s not what the Bible says about historical events. If the message of the Bible were even only “partly true” — that God at least sometimes intervenes to disrupt the normal flow of human affairs — then historians were doing “a disastrous injustice to the biblical text.”

We now follow Dennis Nineham as he leads the discussion into a curious direction, yet one well-trodden by theologians. He infers that this secular view of how historians view the world derives from a singular and now outdated philosophical school of thought. This view of history, he suggests, can be traced back to Hegel, that is, to philosophical underpinnings that have long since been left behind. Accordingly, all reasonable scholars should, by rights, be fair and give serious consideration to the view that there is a God who intervenes in historical events.

Blaming Hegel

The supernaturalist dualism of the philosophia perennis: . . . The view that “this world” is only the visible and less significant portion of reality, and that “the other world”, invisible, beyond space and time, was what gave rise to the visible world. The two worlds are thought to interact, so that things done in this world can have effects in and upon that other hidden world.No doubt the standard historical position was related to the idealist outlook of Hegel and others, which, in sharp contrast to the supernaturalist dualism of the philosophia perennis . . . saw the whole of reality in more monistic terms as a single integrated system. Even those of this way of thinking who believed in God and the supernatural, as many of them passionately did, nevertheless thought of the supernatural and the natural as so integrally related (for example the natural might be thought of as the ‘self-realisation’ of the Absolute) that the interworkings between all the elements could be rationally grasped; all the relationships within the whole . . . could be understood from ‘this side’ , as it were, of the God-world relation. (p. 76)

That is, if God was revealing himself at all he was doing it through entirely natural processes and historical events.

Søren Kierkegaard offers the necessary intellectual cover

Christian scholars have sought sophisticated philosophical grounding for their belief in a God who acts in human affairs as the Bible claims. So Nineham notes the influence in this connection of Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (![]() listen) beyond Denmark from the early twentieth century. The famous theologian and philosopher “had strongly contested this entire [Hegelian] way of looking at things”.

listen) beyond Denmark from the early twentieth century. The famous theologian and philosopher “had strongly contested this entire [Hegelian] way of looking at things”.

Kierkegaard insisted upon “the absolute qualitative distinction” between the natural and supernatural worlds. They could not be seen as indistinguishable, with the physical world being a mere manifestation or expression of the spiritual.

Kierkegaard’s views provided an intellectually respectable context for theologians to return to arguing that the Bible could be accepted to some extent at its face value — as a true testimony for God’s acts within human affairs.

Historie, Geschichte, and “positivist prejudice”

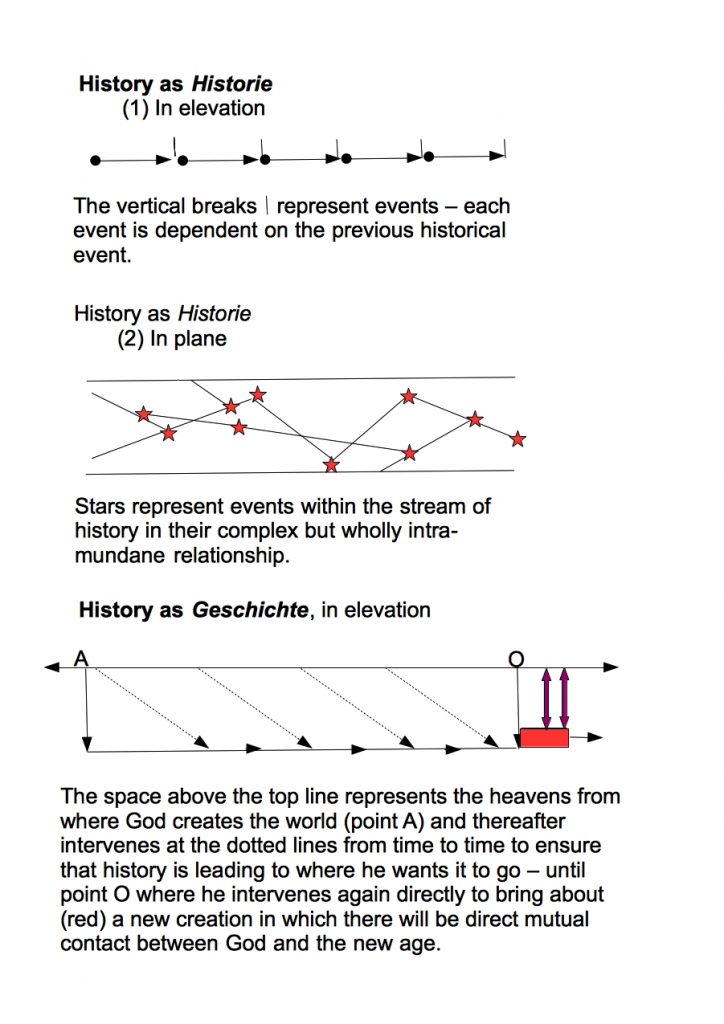

German scholars found the solution in making a distinction of meaning between two words that had up until then been synonyms. Historie (cognate historisch) would henceforth be applied to

the ordinary course of events, historian’s history, events conceived of as all on a horizontal plane, each one — the French Revolution, the Crimean war or whatever — capable in principle of being exhaustively understood on the basis of its lateral relations with other historical events. (p. 76)

I like the way Nineham introduces the geometrical adjectives here, “horizontal” and “lateral”. He’s a true theologian. He will not let his readers (or listeners — his book was originally a series of lectures) lose sight of the theologian’s perspective that the “natural” way of viewing the world and its past is two-dimensional; the implication is that the “full” or “true” perspective of human affairs must introduce a third dimension — the intervention from God above.

Geschichte took on the meaning of history that was

grounded in reality but which saw events as having vertical, as well as horizontal, connexions; saw them in their relationship of total dependence on, and guidance by, active supernatural agency. (p. 77)

Nineham then laments the “unnecessarily limited way” in which English scholars relate “historical phenomena only to what went before and what came after on the horizontal plane.”

If they could only free themselves from what is no more than a positivist prejudice, they could themselves be brought to see that in certain cases, at any rate, such as Jesus’ resurrection or the events of the Exodus, any interpretation which does justice to all the evidence, reviewed without bias, would have to allow for a vertical dimension in which history depends on, and is actively influenced by, transcendent being. (p. 77, bolded text mine)

So we have more mathematical analogies (suggesting a higher precision and truer perspective) coming from the theologians who want a god to be demonstratively involved in human affairs. Of course, what Nineham has invalidly done here is to conflate chronology with secularism. In truth, however, even the supernatural perspective must be subject to chronology: there must have been a point after which and before which God chose to poke his finger into the human affairs of the world.

So the old Homeric notion of different deities swooping down from Mount Olympus to intervene when a favourite Greek or Trojan hero of theirs was coming off the worse in one-to-one combat is given twentieth-century philosophical respectability by limiting the number of deities to one and making the cause of intervention unique to Christianity (and/or Judaism).

I am reminded of the words of one god-believer commenting on a Vridar post who in utmost seriousness suggested that it was quite reasonable to think of “evolution” being guided by a deity hurling meteors or comets into the earth to cause the occasional catastrophe so that the mutating genes of various life-forms would be steered towards becoming a sentient species in the very likeness of God himself!

Nineham then introduces diagrams “to make the matter clearer”:

Of course such a diagram only invites questions, and Nineham well knows this.

How are we supposed to know which events are divine interventions and which are entirely “natural”?

How do we even know if an event truly happened or is not just a construct of theologians? (Enter the questions of the Christ Myth theorists.)

Answers will be revealed in the next post in this series.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“twentieth century philosophical respectability by limiting the number of deities to one”

Why is a single deity more “philosphically respectable” than multiple deities?

Plato

Why the trinity of course!

Shouldn’t comment while tired, I read the first word in RoHa’s question as “what” rather than “why”. My point still stands though.