This post will open by taking us back thirty or forty years to a scenario in Old Testament scholarship that is remarkably similar to a debate taking place right now among New Testament scholars. I am currently reviewing a book, Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity, that spotlights the flaws of the traditional approaches of form criticism and authenticity criteria to the studies of early Jesus traditions and the historical Jesus respectively. The editors of that book, Chris Keith and Anthony Le Donne, argue that attempts to pull apart the Gospels into various strata, pre-gospel Palestinian traditions and stories added by the early Hellenistic Church compiler-author, don’t really work. What is needed is an understanding and study of the Gospels in their final form, they conclude.

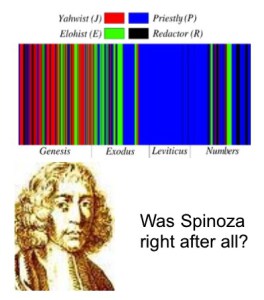

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).

This post continues from an article I posted on Christmas Day last year, Who Wrote the Bible? Rise of the Documentary Hypothesis. It continues with notes on Philippe Wajdenbaum’s case that the “Primary History” of the Bible (Genesis to 2 Kings) was inspired by the writings of classical Greek writings (especially Plato) and mythologies. It is, furthermore, best seen as the product of a single author writing in Hellenistic times. In my previous post on this book I included a quotation from chapter eight of Theological and Political Treatise by seventeenth-century Spinoza, to whom Wajdenbaum refers:

And when we regard the argument and connection of these books [Pentateuch, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings] severally, we readily gather that they were all written by one and the same person, who had the purpose of compiling a system of Jewish antiquities, from the origin of the nation to the first destruction of the city of Jerusalem. The several books are so connected one with another, that from this alone we discover that they comprise the continuous narrative of a single historian. . . . .

I have in the past posted in passing on another book with a similar theme, Jan-Wim Wesselius’ The Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’s Histories as Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible, and I have posted an overview of a section of that book on vridar.info. It is a pity that these sorts of books are priced out of the hands of most potentially interested readers. I have always wanted to post more on the Old Testament books, especially in comparison with other Greek works, in particular works of Herodotus and Plato, and hopefully will do so soon. Too many topics. Not enough time.

Here we continue with Philippe Wajdenbaum’s Argonauts of the Desert, picking up where we left off in December last year. Here he discusses the “collapse of the consensus” on the Documentary Hypothesis and introduces his rationale for proposing a single author for Genesis to 2 Kings.

It is necessary first to overlap with a point made in that earlier post. I elaborate upon it beyond Wajdenbaum’s own brief presentation that was intended for a readership familiar with the scholarly literature.

.

.

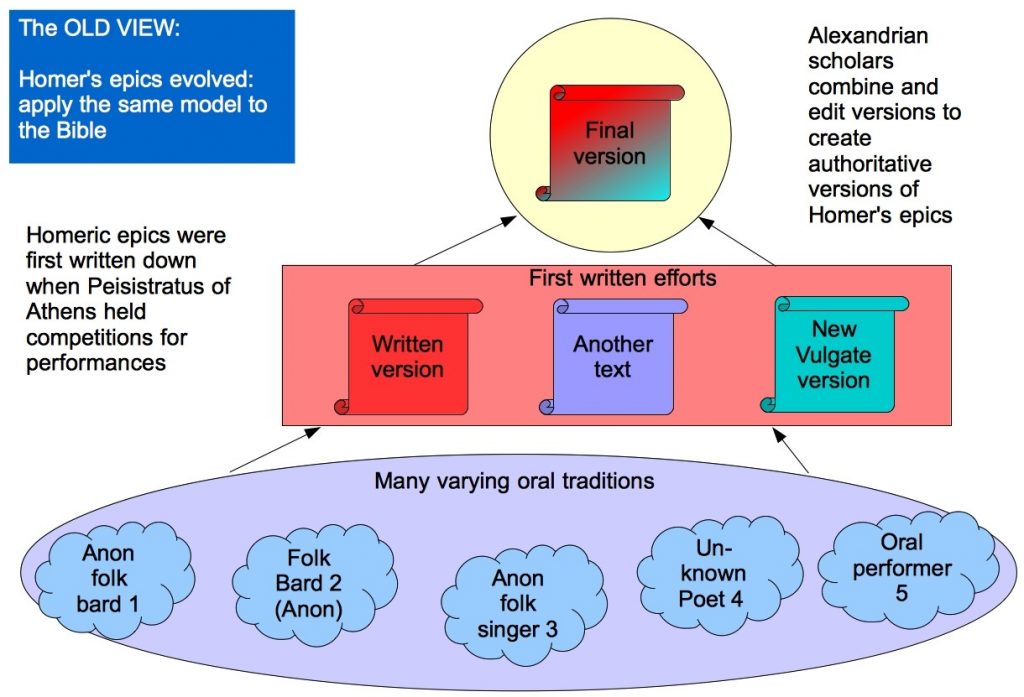

The above diagram demonstrates the old view of how the Homeric epics came into existence. Bards — perhaps one of them was “Homer” — composed and performed songs that were sometimes combined to create larger “epics”, and in the cultural “renaissance” in sixth-century Athens standard versions of these were put in writing to provide a yardstick or canon by which to judge oral performances of the epics.

During the later Hellenistic period scholars in the Alexandrian library created an authoritative or “original” text of Homer by comparing variant written versions that had arisen in the meantime, and making judgments about which lines in which versions were authentic. Thus a “cut and paste” final and canonical edition was created.

That was the theory.

Compare the Documentary Hypothesis: various written versions, Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist, were edited and combined into a new whole by a late redactor to give us our Pentateuch and other historical books of the Bible.

Through the twentieth century, however, the above scenario began to unravel — at least in Classics departments.

John van Seters in The Edited Bible — read the Google version, especially chapter 5 — lays out the evidence that such a notion of an ancient redactor creating a new text by stitching bit and pieces out of various versions is an anachronism. Such a practice was unknown until many centuries later. Rather, the versions created by the Alexandrian scholars never found widespread popularity among the wider readership.

John van Seters in The Edited Bible — read the Google version, especially chapter 5 — lays out the evidence that such a notion of an ancient redactor creating a new text by stitching bit and pieces out of various versions is an anachronism. Such a practice was unknown until many centuries later. Rather, the versions created by the Alexandrian scholars never found widespread popularity among the wider readership.

Besides, the final text was too polished in many ways, and the characterization too consistent and subtle, to be explained by a “cut and paste” job.

Further, oral studies have shown that oral performances have often been associated with memory — after the performer writes it down! — (and there is evidence that the Greek “Dark Ages” did know of writing that went beyond mere book-keeping functions). The sorts of variations that arise through relaying oral performances do not explain the characteristics of our written texts.

.

The theory that the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus commissioned official written versions of the Homeric epics may well be as fictional as the notion among biblical scholars of an historical cultural renaissance at the time of King Josiah. There is certainly no indication in the record that Pisistratid versions were known by Alexandrian scholars or anyone else.

Now the point of this is that biblical scholars developed the Documentary Hypothesis on the back of the old classical model of the evolution of the Homeric epics. That model has crumbled away but biblical scholars have continued to use it regardless.

This brings us to some modern criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis that I will continue in future posts.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neil, are you familiar with the Supplementary Hypothesis as a variation to the Documentary Hypothesis? That might tie up more loose ends as a theory for you than the idea of singular authorship would. Just my hunch, but it’s been a few years since I studied Hebrew Bible composition thoroughly.

The two pages where van Seters discusses the Supplementary Hypothesis are not available on the Google version but one can see from a search on Ewald that van Seters sees this as a variant on the hypothesis of a redactor mixing and matching texts to create a “final” version. This is where the anachronism lies, he argues.

. . . . .

By the way – – –

I have not let through other comments here debating the details of this issue — I mean arguing for alternative theses. For such discussions to be valid, I think, they should indicate knowledge of the details of chapter 5 of The Edited Bible that I have cited in the post. (Of course, I don’t mind questions and other types of comments.)

And of course it should henceforth go without saying that I have no interest in letting through the drivel from the astrotheologians or Murdock’s cult following who have maliciously attacked me personally and demonstrated nothing but faith-based bigotry and intolerance for any criticism whatsoever.

I understand, I just don’t have time to add any more books to the pile right now, least of all books on OT composition. Too curious not to ask this though…how do those who doubt multiple authorship reason through the dual/interlaced accounts of Noah and the flood? If that can reasonably be shown to be the work of one author, then I suppose the entirely of the OT can as well. But I have my serious doubts.

I’m also assuming that you’re familiar with the theory of Martin Noth, since you mention the Deuteronomist above. But his offering to source criticism was the Deuteronomstic History (which place Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings under the pen of the same writer as Deuteronomy’s), but which did not say that the Pentateuch was authored by the same person. Pulling out the D material, from amongst E/J/P, has to be done before linking them to J-J-R-S-K, or else the literary links are thin indeed. Seems that Spinoza was very much on the right track, but that Noth improved upon Spinoza – but only could after identifying Deuteronomy’s difference (or D material’s difference) from the rest of the Pentateuch. Would be interested in your thoughts on this distinction.

These issues will be addressed in future posts, including Noth’s thesis.

As mentioned in another comment here I will probably divert first to a chapter in a 2004 book by Brodie since it covers some of the same material from a slightly different perspective that directly relates to the other methodologies on the historical Jesus I have also been discussing. The bottom line of his argument is that we have been taught to read the Bible through the perspective that these desert middle easterners were a pretty poor lot who could not possibly write sophisticated literature worth comparing with anything like the Greek and Latin classics, but that in recent decades a growing number of scholars have begun noticing the very high level of sophistication in these writings, including Genesis — and even the Gospel of John as a coherent and unified work that was the composition of a single author. Episodic styles and “seams” turn out to be sophisticated emulations and pointers to something far more literary than many scholars have in the past assumed.

Looking forward to criticism of DH. Interested to see how they deal with stories repeated in different versions.

FYI, I read this always on an iPad and the big pictures like these two flow over the text/sidebar border, making both mostly unreadable.

Yeh, I noticed the same on my iPad, too. But I like the exercise of preparing graphics like this because it forces me to scour a wide area of background lit to ensure I don’t miss anything vital and then to distill it to something small to give the quick essence for me to refer to down the track. Maybe I will see if it’s too much trouble to create a simplified iPad version, too.

In preparing my next post on the DH, though, I was led to check out the background to oral traditions as one key step and that wound me back to Brodie’s 2004 book — it’s a very relevant topic for both the DH and the current wave of NT studies now moving to revisions of criteria methods and stepping into social memory. I may digress with a few posts on how ‘oral tradition’ and ‘communities’ became a given in both OT and NT studies before resuming what I had originally intended.

I’ve resized the images — let me know if any problems still exist.

Looks great.

Giovanni Garbini, in Myth and History in the Bible, makes a very good case that the Pentateuch arrived at its final form with Genesis attached around 200 BCE, with the Septuagint coming very soon after. Deuteronomy (along with Joshua) would have been the earliest book, fashioned out of a pre-existing law code after the “exile”, perhaps around 400 BCE. I think Van Seters, Thompson, Lemche, and other minimalist scholars similarly see the final Pentateuch as a Hellenistic work, and the emerging consensus seems to be that Deuteronomy is the earliest portion, before the law code and exodus story were expanded (Exodus to Numbers) and a new narrative of Hebrew patriarchs going back to creation added (Genesis). This is obviously in contrast to the traditional Documentary Hypothesis, which smartly recognizes numerous differing sources in the Pentateuch but has many holes and takes too much of the Biblical history for granted.

On the other hand, Bernard M. Levinson makes a very good case (I think) for Deuteronomy drawing upon the books of Exodus (and Leviticus, iirc) to subvert those codes and replace them with a new one in Deuteronomy and the hermeneutics of legal innovation. His book led me to consider a number of possible applications to the way the gospels were created — and I’ve made brief passing references to this book in a few of my posts on the gospels.

So much in turmoil. I find myself liking contradictory hypotheses.

Are you telling me that nobody has read Ezrah and Nehemiah to date? Given that the Cyrus seal is well known nowadays, I really dont think that folk have to get combative (as the historical Jesus series).

We know where genesis came from because, bizarrely, the hebrew bible tells you where and when, how and why and finally, who and who the attributions belong.

I look forward to another fascinating series Neil and will keep my rather boring comments to a minimum (as usual).

Apsu’s watching you….from a distance!

(Be that as it may, I would still recommend water wings).

Is there a good book explaining “the new view” on Homer?

See van Seters’ bibliography.

Keith and Le Donne verge on apologia and Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity contains a collection woefully typical of it’s context with mixed muddle of typically conservative flaws and inaccuracies and misrepresentations out of touch with broader advances in knowledge. Wellhausen’s theory has not only been challenged, it has been effectively replaced with more recent recognition of contemporary scribal habits and editorial practices. The work of other ancient authors, copies of whose work are extant, demonstrate a drastic rewriting of sources, tending to follow only one source at a time, adapting with modification or alteration, eliminating repetitive material, bringing sources together in a new narrative, expanding rather than eliminating. This is demonstrated by Derrenbacker, in Ancient Compositional Practices and the Synoptic Problem, 77-117 in his analysis of the texts of ancient authors such as Josephus, Diodorus Siculus, Arrian of Nicomedia, Strabo and Josephus.

Can you point to specifics to make your case against Le Donne and Keith or do independent scholars deem it sufficient to trash with rhetoric alone?

Derrenbacker’s work has been well known for some time now, but compositional practices as he discusses them are not quite the same as the creative authorial processes that we are beginning to address in this post. Have you read much in the area of ancient rhetoric?

Yes and obviously not in a blog comment. It’s good to see you’ve taken it up to fully review it yourself. Refutation of Le Donne, Keith and others forthcoming in “Jesus:” Casey (T&T Clark) now also including discussion of recent publications from Le Donne, Thompson, etc. I discuss this and also Derrenbacker in particular including Derrenbacker in the context of a discussion on Wellhausen’s theory in the context of a refutation of Delbert Burkett’s references to it. And yes indeed, Derrenbacker’s work was published in 2006. And yes, of course, it’s essential to any source theory hypotheses, in understanding any ancient writing, ancient history at all, and like most historians our degrees include ancient history/classics.

So you can’t even mention a single specific detail in order to present a single reasoned argument but tell us we have to read your whole chapter instead. You are the only scholar I know who has a track record of being self-admittedly incapable of giving an abstract or a single sample argument. But this is not Joseph Hoffmann’s or James McGrath’s blog so you will have to keep to standards of civil and reasoned discussion here. Simply dumping put-down rhetoric against arguments of others while failing to actually give a reasoned and evidence based response is not good form. If you can’t do that in a blog comment then you should not comment on this blog but stick to Hoffmann’s and McGrath’s.

As for your response to my last question, I am prompted to ask if you are in politics. You have a knack of giving a response without answering the question. On this blog others do notice. I take it your direct answer would be “no”.

The Documentary Hypothesis is a terrible explanation for composition. One of its main proponents today, RE Friedman, has mistranslated and worked his magical editor into his works such as The Bible with Sources Revealed. I have personally seen his errors. Some of his grad students disagree with him because more recent scholarship is revealing a singular author position. I don’t think it was Moses, but I am of Umberto Cassuto’s position that the Pentateuch received much of its from by the time of King David. Archaeologically, this is more than a viable possibility.

Can you give an example of the errors? What has Friedman himself said about them?

It’s common for students to come to different views from their teachers as they ask different questions and are exposed to new evidence. It’s not uncommon, either, for professors to change their views over time. Or at least until that happens it’s common to see them engage with new interpretations.

Have these new ideas been discussed with Friedman for his own feedback? I like to hear exchanges like that — often learn heaps that way.

The Documentary Hypothesis is flawed due to circular reasoning in that it seeks to explain the OT’s revolution by relying on the chronology and events described by the OT, all the while admitting that the OT is an inauthentic document and, therefore, unreliable.

And if there was a King David, his is not the life described in the OT. That privilege belongs to Ptolemy I. The reason why there’s so much “truthiness” to the stories of David and Solomon is that they were based on the biographies of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II. The Primary History is first and foremost a Hellenistic Era document.