This continues the previous post that introduced Edmund Cueva’s study in the way our earliest surviving Greek novel was composed by combining historical persons, events and settings with fictional narrative details and characters that were inspired by popular myths.

Cueva is not comparing these novels with the gospels, but I do think it is important to compare them. There are quite a few studies that do argue that many of the details in the gospels narratives, even some of the characters, were copied from older stories found in both the Old Testament and in popular Greek literature. This would mean that the gospels are not unlike some popular Greek novels to the extent that they are stories that combine both historical and fictional characters and events in their story, with those fictional characters being conjured up by imaginative extrapolations of mythical characters.

In the previous post I focused mostly on the historical characters and events that are major players in Chariton’s novel Chaereas and Callirhoe.

In this post I outline some of the evidence that the heroine of the novel and her adventures were imaginatively inspired by popular Greek myths, especially those about Ariadne and Theseus. (I do so with apologies to Cueva, too, because what I include from his discussion is necessarily a savage simplification of his arguments for mimesis. Cueva includes in his discussion verbal echoes between Chariton’s novel and Plutarch’s Life of Theseus, and discusses more characters than just the heroine, Callirhoe.)

| Myths of Ariadne | Callirhoe, the heroine in Chariton’s novel |

| .

. . . . Ariadne was the daughter of Minos who was king of the dominant seafaring power of Crete. Minos had attacked Athens, and ordered an annual tribute of 7 men and 7 women to be sent to Crete as sacrifices to the Minotaur. Plutarch in his Life of Theseus informs readers of six different versions of the Ariadne tale: Version 1: Theseus deserted Ariadne in Naxos, and she then hanged herself. Version 2: Ariadne was taken prisoner by sailors to Naxos. Version 3: Theseus abandoned Ariadne because he was in love with someone else. Version 4: Ariadne bore to Theseus two sons, Oenopion and Staphylus. Version 5: See the account by Paeon below. Version 6: Some Naxian writers said there were two Minoses and two Ariadnes:

Version 5 (Paeon’s version): Plutrarch’s account of Paeon’s narrative:

Plutarch continues with:

Plutarch in the same account of The Life of Theseus informs readers that according to Cleidemus there was a rule that a crew of only five could set sail at the orders of King Minos to pursue Daedalus. |

Chariton portrays Callirhoe as physically like Aphrodite, but it is the myth of Ariadne that to direct the much of the plot.

“She was a wonderful girl, the pride of all Sicily; her beauty was more than human, it was divine, and it was . . . of the maiden Aphrodite herself.” [See Paeon’s association of Ariadne with Aphrodite in the left column.] Callirhoe is the daughter of the general Hermocrates who had made a name for himself at seafaring and had gone to war with Athens. Callirhoe marries Chaereas who unintentionally causes her apparent death by kicking her in the stomach. [Ariadne is also pregnant at this time with Chaereas’s child. cf Paeon’s version in left column.] The apparently dead Callirhoe is compared with the sleeping Ariadne on the shore of Naxos. [cf. Ariadne versions 1 and 3] Callirhoe, appearing dead, is entombed. She recovers in the tomb, but pirates, led by Theron, break in and then sail away with her to sell her as a slave. [cf Ariadne version 2] She is sold and many “countrywomen came to see her, and at once they began to make up to her as if she were their mistress. . . ” (Reardon, p.39) [cf Paeon’s version of Ariadne] Callirhoe then is married to the Milesian nobleman, Dionysius. [cf Ariadne version 6] When Chaereas returns to Callirhoe’s tomb and discovers it is empty, he “looked towards the heavens, stretched up his arms, and cried:

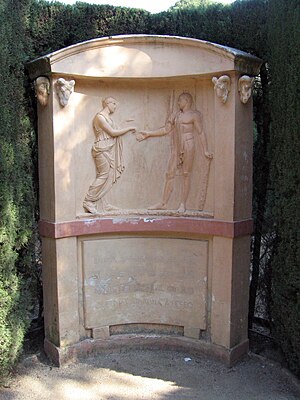

Theron, the pirate who kidnapped Callirhoe, is captured and returned to Hermocrates, Callirhoe’s father, for trial. He idenitifies himself as being from Crete, tells them where he sold Callirhoe, and is then sentenced to crucifixion. Many want to go out and recover Callirhoe, but Hermocrates orders that a crew of only five, including Chaereas, be sent. [cf Plutarch’s account of Minos sending a ship in pursuit of Daedalus] Chaereas and his crew sail to Miletus. There he sees a statue of Callirhoe in the temple of Aphrodite. [cf Ariadne version 5 by Paeon] It was said that Callirhoe’s name was more celebrated thoughout Asia than Ariadne’s. Letters and forgeries [cf Paeon’s story]: Callirhoe has been married to the nobleman Dionysus. Chaereas writes a letter to Callirhoe but this letter is intercepted by Dionysus. He believes the letter is a forgery and really sent by a love rival, Mithridates. Dionysus then writes a letter to the Persian governor (who is also a love-victim of Callirhoe), and the governor in turn writes a letter to the Persian king, Artaerxes (who will also fall in love with Callirhoe). At the end of the story, after Callirhoe has been united with Chaereas again, Callirhoe writes a letter to Dionyius begging him to take care of their son. But in fact, unknown to Dionysius, the child’s father is really Chaereas. [cf Ariadne versions 4 and 6: Callirhoe has one son but he appears as the son of both Dionsyius and Chaereas.] Before returning home to Syracuse, Chaereas had been involved in a battle in Egypt and had recovered for the Persian king, Artaxerxes, his wife Statira. [Cf previous post: Artaxerxes did historically have a wife Statira.] On their return to Syracuse, Chaereas’s ship is not recognized and thought to be an enemy ship. The mistake is quickly corrected, however, thus avoiding further calamity. [cf the myth in which Theseus forgets to indicate his ships identity as he nears home, and causes the death of his father.] After Dionysius read Callirhoe’s letter asking him to care for their son, he returns to Miletus and sets up numerous statues of her.

|

Related articles

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

0 thoughts on “Ancient Novels Composed Like Gospels continued (2)”