I have not been able to fully grasp why some nonbeliever historians are so strident in their insistence that there is strong evidence for a historical Jesus and refuse to even contemplate for a moment, along with their believing peers, that they might be violating the simple foundational basics of practical historical enquiry. These basics, and the failure of historical Jesus historians to use them or even be aware of them are discussed in my earlier post:

- the nature of historical facts and the contrast between nonbiblical and historical Jesus historical methods

- and in a follow-up post discussing Scot McKnight’s discussion of biblical historiography.

But the reason has hit me. It came from reading follow-up works cited by Warsaw University lecturer, Dr Lukasz Niesiolowski-Spano (Primeval History in the Persian Period? 2007). These were Intellectuals and Tradition by S. N. Eisenstadt (Daedalus, vol. 101, no. 2, Spring 1972, pp.1-19) and Intellectuals, Tradition, and the Traditions of Intellectuals: Some Preliminary Considerations by Edward Shils (Daedalus, vol. 101, no. 2, Spring 1972, pp.21-34).

And the reason is now so obvious I am kicking myself for not seeing it earlier. If I did see it earlier it was only murkily.

History is always necessarily created by a society’s intellectuals. They shape the images that a society sees about itself and its past — its identity.

The sociological study of tradition has argued . . . that the formation of traditions is the activity of an intellectual elite, not the work of the community as a whole. This runs counter to a position often expressed or presumed in biblical studies. Yet S. N. Eisenstadt specifically identifies society’s intellectuals as the “creators and carriers of traditions.” This is true for many different kinds of tradition, including that of the historical traditions. The historian, as an intellectual, is the creator and maintainer of historical tradition. E. Shils makes the statement:

Images about the past of one’s own society, of other societies, and of mankind as a whole are also traditions. At this point, tradition and historiography come very close to each other. The establishment and improvement of images of the past are the tasks of historiography. Thus historiography creates images for transmission as tradition.

Of course, there may be a great many inherited images of the past — traditions of almost infinite variety. But their selective collection and organization according to chronological and thematic or “causal” relationships is the intellectual activity of historiography. (pp. 34-35 of Primeval History)

What has modern historical Jesus research been about if not an attempt by different scholars to establish and improve our culture’s most central iconic image?

It has become a truism to say that historical Jesus scholars tend to find (create) a historical Jesus who fits very neatly with their own particular values and ideologies.

Is not this, then, evidence that what the historians are doing is attempting to redefine society’s central icon to advance a certain set of understandings and values that they favour for society as a whole.

History wars – hostile and benign – and the nature of history

We know about the history wars in more recent historical topics. We know the battles that have raged between historians who are accused of being overly critical of their nation’s past and those who are accused of attempting to preserve myths and ideologies of power. The former are feared as a potential threat to national loyalty and cohesion; the latter a realized threat to the rights and justice for minorities. In India these intellectual “history wars” have resulted in very real bloodshed.

The same, of course, must apply to Jesus studies. Jesus is not a national founder, but he has been definitely and definitively the central icon of western culture.

James Crossley is very much politically inclined to something we can still call “the left”. His Jesus is a figure at the centre of economic and related sociological forces at work, as per (slightly modified) models such as those by socialist historian Eric Hobsbawm.

For a historical Jesus historian to even contemplate a critical examination of their methodological assumptions (I mean radical examination as in the posts I link to above) to the extent that risks exposing the illegitimacy of the whole enterprise, is to risk their conduit for intellectual expression altogether.

Can a national historian ever doubt the existence of conflicts between European invaders and indigenous inhabitants? One historian studies them to expose past wrongs and raise public awareness of ethical issues. Another historian studies them to present an image of flawed humans in the process of advancing a nation’s identity and economy. If someone discovered that all the documents they were using as their sources were somehow faked, there would be trauma, denial. It is not the past that is at stake. It is the many debates about contemporary values and beliefs that history is really all about.

It has always been thus. That’s what history is.

And that is also why, I believe, even nonbeliever historians find a historical Jesus such an important figure.

In Switzerland some people still refuse to accept what for them is simply unthinkable – the discovery that William Tell was not historical. In India, belief in the historical Rama is among some people about contemporary political, religious, economic and social relationships. For a modern secular historian, Jesus can be a focus for explaining a certain way how society works, or for explaining positive or dysfunctional ways to respond to how it works.

The evidence for his historical existence does not matter. It is always assumed, or what is declared is either subjective or dismissive/ignorant of normal (nonbiblical) standards. What matters are the different positions in this particular (benign) “history war” of competing ideologies, beliefs and values about the wider world and humanity.

So where does this leave mythicists?

If this is how it is, then of course mythicists have no place in such an enquiry. They are at cross purposes. One is doing methodical research into the origins of Christianity without presupposing a historical figure at the centre of it; the other is doing research into how Christian origins, according to the cultural iconic starting point, can be molded into images that help us understand something significant about ourselves and our world today.

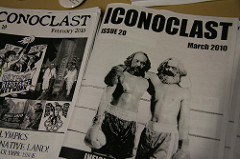

The historian who does not make assumptions about the existence of Jesus, but who approaches the evidence with a view to understanding what it tells us about origins, whether or not that points to a heroic figure at its start, becomes, I suppose, an iconoclast if those studies lead him or her to find no need or room for the icon. (Like Darwin, Galileo . . .) That’s when the other side tends to start name-calling and imputing negative motives, ridiculing and circling the wagons.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I’m fairly sure Chomsky, with or without Herman, has written at length and pointedly about the role of intellectuals as the trustees and creators of orthodox traditions. Most of my Chomsky books are scattered around friends and rellies so I can’t check for exact quotes but I reckon you could find where he [they] have given this topic consideration.

http://www.chomsky.info/books/responsibility01.htm

This is from a google search “chomsky/orthodox/intellectuals” and will give a taste of a broad treatnent:

“For example, take the question of the role of the intelligentsia in a society like ours. This social class, which includes historians and other scholars, journalists, political commentators, and so on, undertakes to analyze and present some picture of social reality. By virtue of their analyses and interpretations, they serve as mediators between the social facts and the mass of the population: they create the ideological justification for social practice. Look at the work of the specialists in contemporary affairs and compare their interpretation with the events, compare what they say with the world of fact. You will often find great and fairly systematic divergence. Then you can take a further step and try to explain these divergences, taking into account the class position of the intelligentsia.

Such analysis is, I think, of some importance, but the task is not very difficult, and the problems that arise do not seem to me to pose much of an intellectual challenge. With a little industry and application, anyone who is willing to extricate himself from the system of shared ideology and propaganda will readily see through the modes of distortion developed by substantial segments of the intelligentsia. Everybody is capable of doing that. If such analysis is often carried out poorly, that is because, quite commonly, social and political analysis is produced to defend special interests rather than to account for the actual events.”

There are a couple of key phrases/concepts there eg:

“they serve as mediators between the social facts and the mass of the population: they create the ideological justification for social practice …….anyone who is willing to extricate himself from the system of shared ideology and propaganda will readily see through the modes of distortion developed by substantial segments of the intelligentsia.”

He has written some interesting stuff on the political role of ‘experts’.

Chomsky is the heir of Julien Benda who first addressed the betrayal of the modern intellectuals.

This is one reason Crossley’s Jesus in the Age of Terror disappointed me in some ways. It was good as far as it went, and I quite liked much of it, but it did not go very far beyond the surface issues of attitudes towards political stances involving the Middle East etc. He quotes and links to all the right people with the Chomsky-like critical credentials regarding media and politics and power. But he misses the really core point running through Chomsky’s critique about intellectuals and their public responsibility. Crossley jumps on the bandwagon of Chomsky’s specialities of public politics. But he fails to see how he himself is part and parcel of myth-making in support of certain cultural institutions. I suppose he can think that he is justified because his supports are for “the right side of humanity”. Chomsky’s critique demolishes myths, though, and his talks are “boring” (by his own admission) because they are chock-heavy with fact after fact after fact. Crossley comes across as a Chomsky-dilettante when one examines his own historical work expecting to find consistency with the presumed integrity of his public politics.

http://vridar.wordpress.com/2010/04/21/chomsky-crossley-and-the-betrayal-of-an-independent-approach-to-historical-jesus-studies/

Neil wrote: “If someone discovered that all the documents they were using as their sources were somehow faked, there would be trauma, denial. It is not the past that is at stake. It is the many debates about contemporary values and beliefs that history is really all about.”

I’m glad you can see his important point…

Mythicists are not simply up against the biblical historians, whether of the apologetic sort or the secular. They are up against a secular, political, intellectual tradition that has been infiltrated by Christian theology. The French Revolution may have desecrated the churches – theology simply jumped ship to the secular intellectuals and masqueraded as a moral political and economic ideology. That is where it’s power is today: Within political democracy and its various intertwined economic systems.

Social political structures that cannot function without a ‘morality’ based upon the Cross. Upset the apple cart re there being no historical Jesus and no self-sacrifice crucifixion – the whole western political theory falls flat on its face.

Self-sacrifice as a code of intellectual evolution – old ideas being given up in order for new ideas to be generated – is one thing. It is quite another thing for this type of code, of action, to be allowed to function within a social/political structure. Passing the sacrifice ‘buck’ becomes a run around until someone, or some group, is persuaded to sacrifice in order for the waiting human vultures to be the beneficiaries. Thus a society of losers and looter. With a permanently frozen divide between the rich and the poor, between the looters and the losers.

And the grand altar upon which all the political sacrifices take place? The Ballot Box. In effect, the ballot box has become a juggernaut that inhibits the exercise of objective, rational though and action – a scenario not unlike that faced throughout history when the reputation of a conquering army psychologically disarmed the local population.

Christian theology, with its coat of many colours, has found a far more profitable exercise of its mystical hold in democratic political power.

Little wonder that there is no rush to clarify the historical underpinnings of the gospel storyline. The bottom would fall out of the social/political world as we know it….

maryhelena.

Yes, well put.

There is a good example of this in action in Australia currently.

The current leader of the opposition party in out parliament has told a group of 10-11 year old school students that climate change is doubtful because in the time of Jesus the middle east was warmer than it is now.

[Here is a link for a bit more specific background.

http://hoydenabouttown.com/20100511.7508/obligatory-tony-abbott-said-what-now-thread-ii/

The link summarises his words as “his [the politician in question]explanation to schoolkids that global warming couldn’t be any sort of problem because it was hotter back ”at the time of Julius Caesar and Jesus of Nazareth”]

Now there are several disturbing aspects to this little event not least of which is the absence of any historian jumping up in the media and questioning the presumption of an historical Jesus and attendant ‘details’. Its simply taken for granted that this is an an acceptable given fact.

If you were a historian in this country would you dare to publicly question the given?

Yes, its quite amazing how people use the assumed events of 2000 years ago as some sort of measuring stick that has real relevance for our modern world. Storytellers, whoever they are, priests, politicians and intellectuals, need to be questioned. Perhaps the fault lies just as much with those who don’t question as with those who spin the stories. No one has ‘truth’ tied to their back pockets…

As for scholars – great, give them respect for their learning but never the ultimate say so on issues with which we might have some thoughts of our own. Remember that old saying – one can take a horse to water but one can’t make it drink. Something that academics and intellectuals should keep in mind when they seek to relate their ideas.

Paul Johnson had a good take on things:

“…I think I detect today a certain public scepticism when intellectuals stand up to preach to us, a growing tendency among ordinary people to dispute the right of academics, writers and philosophers, eminent though they be, to tell us how to behave and conduct our affairs. The belief is spreading that intellectuals are no wiser as mentors, or worthier as exemplars, then the witch doctor or priests of old….A dozen people picked at random on the street are at least as likely to offer sensible views on moral and political matters as a cross-section of intelligentsia……..I would go further……- beware intellectuals………Above all, we must at all times remember what intellectuals habitually forget: that people matter more than concepts and must come first. The worst of all despotisms is the heartless tyranny ofr ideas”. (Intellectuals).

And on that note – and in relationship to the whole literal Jesus crucifixion idea and its foray into a ‘morality’ for secular/political structures – Dawkins said it best:

“Among all the ideas ever to occur to a nasty human mind (Paul’s of course), the Christian “atonement” would win a prize for pointless futility as well as moral depravity”.

Its an insidious idea – we do well to keep a look out for its political grandstanding….

From my limited experience on forums & blogs (not academia!), I think a significant factor in the atheist defence of an historical Jesus is an attempt to portray themselves as reasonable, rational people who are willing to accept evidence even if they don’t like it. Perhaps they think that if they show they can make this concession then their opponents will make concessions of their own. In many cases they believe that an historical Jesus is a consensus of the relevant experts and we should respect this, just as we do in other fields. They may be aware of how “evolution sceptics” disingenuously argue that they are merely interpreting the evidence differently so when mythicists use a similar-sounding argument, they think the mythicist argument is as dishonest and faith-based as the Creationist/ID one.

I think this is right for most instances, and I don’t see much wrong with it in normal circumstances. The problematic issue is among the historians specializing in the historical Jesus. The wider consensus that exists ultimately has its source in them. They are the ones who are culturally egg-bound.

“One is doing methodical research into the origins of Christianity without presupposing a historical figure at the centre of it;”

But this cannot be done. There obviously must be a central historical figure in the origins of Christianity (even if it isn’t Jesus), namely the author of the first gospel. (And I do not mean canonical Mark.)

Or the author/s of the letters of Paul. What I meant is the study of the earliest Christian and Christian-like/related literature with a view to seeking the best explanations for its origins by means of internal and external evidence. This differs from current Christian origin studies which instead attempt to explain the literature in terms of the models that are all variations of the gospel-Jesus-Acts model. Or they attempt to revise and refine that model by the study of the literature.

This was the mistake made by the Albrightians with the Hebrew Scriptures. They attempted to explain the external evidence, and the biblical literature, in terms of a historical Kingdom of David etc. Or they attempted to refine their model of the Kingdom of Israel through their study of the literature.

What they were doing was assuming that the narrative in the Bible had a historical core, and what scholars needed to do was to refine or flesh out that core, or interpret the Bible literature in the light of that particular “history”.

But the work of the so-called “minimalists” has resulted in a growing tendency to interpret and explain the literature about David, for example, in the light of external evidence. This has meant accepting the possibility that David is a fictional character. The story of the united kingdom has more to do with propaganda from much later times.

With the gospels and the historical Jesus, we don’t appear to have the ability of archaeological evidence to overturn the assumptions of historicity.

But what should have been learned from the Jewish Bible experience is that the method of assuming that a single narrative has a historical core despite the lack of external controls to support it is indefensible. The defensible study of the literary evidence is to approach the Gospels in the same way that scholars are beginning to learn to approach the literature about David etc. That is — to approach it in the same way ancient and classical historians generally approach documents and historical reconstructions.

This leads to the historian explaining the literature and events in terms of “movements”, “schools”, competing and emerging ideas, — instead of in terms of discovering the “historical” Robin Hood or David or Jesus.

Neil,

Stop using the word “nonbeliver” or “unbeliever”. All adults over age 5 believe things. Use a term like “christians” or better yet “supernaturalists”. Do not continue to imply that the word “beliver” is owned by supernaturalists.

Words are important. Allowing supernaturalists to “own” the word “believer” is a mistake.

It implies that supernaturalistic belief is so important that when the word “belief” is used, by default it means belief in that. If we want to marginalize supernaturalism, we need to not imply that belief in the supernaturalism is so dominant that when the word “belief” appears with no qualifier that it means belief in the supernatural.

Cheers!

RichGriese.NET