It has become a mantra in almost any book that raises the question: Why did the evangelists insist Jesus was from Nazareth unless it happened to be an undeniable historical fact known to all? The mantric response: Because no-one would make up such a datum; no-one would make up the notion that the great and saving Jesus came from such a tin-pot village. The criterion of embarrassment screams against the very idea.

It has become a mantra in almost any book that raises the question: Why did the evangelists insist Jesus was from Nazareth unless it happened to be an undeniable historical fact known to all? The mantric response: Because no-one would make up such a datum; no-one would make up the notion that the great and saving Jesus came from such a tin-pot village. The criterion of embarrassment screams against the very idea.

I have never jumped on board with that response because I have never encountered any evidence that demonstrates why it would be too embarrassing for anyone to imagine that the Lord who taught the overturning of the social order so that the last would be first and the first last, who taught that God will exalt the humble and bring low the mighty, — that it would be too embarrassing for anyone to write down for posterity such a detail unless it were historically true and widely known.

I have always considered that response to be ad hoc. It is a speculative opinion but nothing more — pending evidence to buttress its presuppositions.

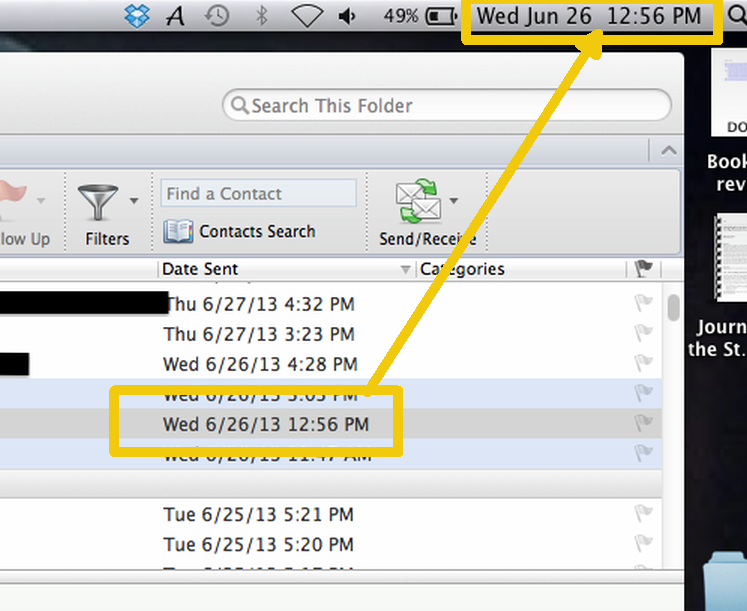

Then yesterday I read in the work of an ancient historian about the humble birthplace of a Roman emperor, the humble birthplace of a man who was decreed to be a god. The detail is presumably factual. The historian said it was well-known so there was no point trying to hide it. But there’s a catch, a catch that overturns the premise of the above ad hoc and almost universal explanation among scholars for the reason the evangelists might not have fabricated Nazareth as the hometown of Jesus. Here is the passage from the Roman historian Suetonius:

[The Roman emperor] Vespasian was born in a little village in the Sabine land just beyond Reate, known as Falacrina. [Deified Vespasian, 2]

Was this historical record an embarrassment to Vespasian? It seems not, since

even when he was emperor, he would frequently visit his childhood home, where the house was kept just as it had been so that he would not miss the sight of any familiar object. And he so cherished the memory of his grandmother that on religious and festival days he would insist on drinking from a small silver cup which had belonged to her. [Deified Vespasian, 2]

But wait, there is more:

In other matters he was from the very beginning of his principate [emperorship] right up until his death unassuming and tolerant, never attempting to cover up his modest background and sometimes even flaunting it. Indeed, when some people attempted to trace the origins of the Flavian family back to the founders of Reate and a companion of Hercules, whose tomb stood by the Salarian Way,* he actually laughed at them. [Deified Vespasian, 12]

Humble beginnings of a person who rose to high status could well be interpreted as evidence of special divine favour.

Even the great Augustus, the one emperor Suetonius took the most seriously as a divinity, is noted for his humble place of birth. Not the slightest hint of embarrassment is evinced in Suetonius’s reporting of it:

Augustus was born a little before sunrise eight days before the Kalends of October in the consulship of Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius, at the Ox Heads in the Palatine district, on the spot where he now has a shrine, established shortly after he died. For, according to senate records, one Gaius Laetorius, a young man of patrician family, in an attempt to mitigate a penalty for adultery, which he claimed was too severe for one of his age and family, also drew to the attention of the senators the fact that he was the possessor and, as it were, guardian of the spot which the Deified Augustus first touched at his birth, and sought pardon for the sake of what he termed his own particular god. It was then decreed that this part of the house should be consecrated. To this day his nursery is displayed in what was his grandfather’s country home near Velitrae. The room is very modest, like a pantry. [Deified Augustus, 5-6]

Suetonius introduces the above passage after having portrayed other indicators of Augustus’s humble early years and even detailing accusations of Augustus’s enemies about his origins:

In the first four chapters the biographer has compiled an account of the Octavii and the Atii, the gentes of Augustus’ natural parents, which sets out the comparative humbleness of his origins: the princeps’ own claim that his paternal line was an old equestrian family is juxtaposed with the claims of M. Antonius that it was tainted with the servile and banausic – a great-grandfather who was an ex-slave and a grandfather who was a money dealer. As to the maternal line, against the claims of senatorial imagines, Antonius alleges a potentially non-white ancestor and more of the banausic – a great-grandfather of African origin who moved into the baking business after running a perfume shop. This section of the life ends with an extract from a letter written by Cassius of Parma, assassin of Caesar and notorious victim of Augustan revenge, which combines both strands of Antonius’ attack and adds a sexual dimension:

. . . . Your mother’s meal came from the roughest bakery in Aricia; a money changer from Nerulum pawed her with his hands stained from filthy pennies. [Deified Augustus, 4.2]

Although Augustus’ ancestry was not the obvious stuff of gods, the next chapter, which begins the Life of Augustus proper, marks a transfer of focus: . . . .

[See the Suetonius passage above: Augustus was born a little before sunrise . . . .]

It begins by recording that Augustus (Suetonius deliberately uses the anachronistic name) was bom in a modest part of Rome, but then qualifies that by ubi nunc habet sacrarium, which begins a series of references to his divinity. (Wardle, 323-24)

Now we may accept the above accounts as likely historically true, but the point is our historian betrays not a hint of embarrassment. The tone suggests that there is nothing inappropriate about one destined to become a god should be born in humble or obscure circumstances.

I know, I know, there are a dozen spin-off questions relating to the above post. But I have chosen to focus on just one point.

Suetonius. 2008. Lives of the Caesars. Translated by Catharine Edwards. Reissue edition. Oxford etc.: OUP Oxford.

Wardle, D. 2012. “Suetonius on Augustus as God and Man.” The Classical Quarterly 62 (1): 307–26.

Like this:

Like Loading...