Based on my reading of the first chapter of The New Threat: The Past, Present, and Future of Islamic Militancy by Jason Burke. . . .

Based on my reading of the first chapter of The New Threat: The Past, Present, and Future of Islamic Militancy by Jason Burke. . . .

The turning point was in October, 1981, argues Jason Burke. Prior to the 1980s the most well-known terrorists were Leila Khaled and Carlos the Jackal. Religious agendas were very rarely found in the mix of ethnic, nationalist, separatist and secular revolutionary agendas.

The terrorist act that changed all this was the assassination of President Anwar Sadat of Egypt in Cairo in October 1981. Sadat’s killers were very different from most of the terrorists of the decade before. (p. 24)

An ideological movement had taken root in the broader Muslim world — “a generalised rediscovery of religious observance and identity, coupled with a distrust of Western powers and culture.”

The historical matrix

History is necessary to enable us to understand. Burke points to the century between 1830 and 1930. These years saw the Russians, the Han Chinese and especially the Europeans invade and subjugate the Muslim regions from Morocco to Java, from the central Asian steppes to sub-Saharan Africa.

Almost all the invasions provoked a violent reaction among many local people. Resistance took many forms but, naturally enough in a deeply devout age, religion played a central role. Islam provided a rallying point for local communities more used to internecine struggle than campaigns against external enemies. (p. 25)

European armies and their local auxiliaries fought rebels whose motivations ranged widely but who all shared

a profound belief that they were acting in defence not only of their livelihoods, traditions and homes but of their faith.

The superior technology of the foreign powers guaranteed the defeat of the rebels but these defeats were interpreted by the devout as evidence that they had neglected to please God and lost his favour.

Though by the twentieth century most movements had withered away a few remained active: British India’s North-West Frontier, Italian Libya, Palestine. The Afghans were not ruled by foreigners but in the 1920s they did throw out their king who had attempted to introduce foreign ways into his country.

Others chose withdrawal to open revolt, and to isolate themselves from the corrupting influences of alien cultures: e.g. the Deobandi school of India.

Some, however, fully embraced Western ideas in a spirit of rivalry. They sought to out-do their invaders: e.g. the University of Aligarh.

Ed Husain (author of The Islamist and previously posted about here) recalled as a boy growing up in a mainstream Muslim household when and the context in which he first heard the name Maududi:

Ed Husain (author of The Islamist and previously posted about here) recalled as a boy growing up in a mainstream Muslim household when and the context in which he first heard the name Maududi:

“I liked Grandpa. Most of all, I used to delight in watching him slowly tie his turban, wrapping his head with a long piece of cloth, as befitted a humble Muslim, though he also seemed like a Mogul monarch. (Muslim scholars and kings both wore the turban in veneration of the Prophet Mohammed.) Whenever Grandpa visited Britain to teach Muslims about spirituality, my father accompanied him to as many places as he was able. My father believed that spiritual seekers did not gain knowledge from books alone, but learnt from what he called suhbah, or companionship. True mastery of spirituality required being at the service, or at least in the presence, of a noble guide. Grandpa was one such guide. . . .

“He often read aloud in Urdu, and explained his points in intricate Bengali, engaging the minds of others while I looked on bewildered. As they compared notes on abstract subjects in impenetrable languages, I buried myself in Inspector Morse or a Judy Blume. I heard names such as ‘Mawdudi’ being severely criticized, an organization named Jamat-e-Islami being refuted and invalidated on theological grounds. All of it was beyond me.” (The Islamist, p. 10, my bolding)

What interests us, however, are those who took the middle road. The first was the work of Abd Ala’a Maududi [Abul Ala Maududi/Maudoodi/Mawdudi]:

In India, a political organisation called Jamaat Islami was founded in 1926. It sought religious and cultural renewal through non-violent social activism to mobilise the subcontinent’s Muslims to gain power. This approach involved embracing Western technology and selectively borrowing from Western political ideologies, while rejecting anything seen as inappropriate or immoral. (p. 26)

.

In Egypt, 1928, Hassan al-Banna founded a very similar group, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Like the South Asian Jamaat Islami, it combined a conservative, religious social vision with a contemporary political one. For its followers, the state was to be appropriated, not dismantled, in order to create a perfect Islamic society. This approach was later dubbed Islamism.

There were others across the Muslim world who rejected the compromise and non-violence of Jamaat Islami and the Muslim Brotherhood as the means to achieving their common goals.

By the early 1960s European powers had for most part withdrawn from the Muslim world leaving behind new regimes that had adopted Western ways and ideas: witness the new states founded in varying degrees of secularism and socialism. And of course there was Israel:

The establishment of the state of Israel, now recognized by the international community after a bloody war and the flight of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from lands they had worked or owned for generations, acted as a new focus for diverse grievances among Arab and Muslim communities. Anti-Semitism had long existed in the Islamic world but, fused with anti-Zionism, gained a new and poisonous intensity. Defeat in the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 deepened a sense of hurt, loss and humiliation. (p. 27)

Something more important was happening within the newly independent nations themselves: “immense demographic change”.

- Population explosions

- Urban population mushroomed and rural populations relatively declined

- Urban areas of poverty and unhealthy conditions proliferated — inadequate electricity, sanitation, education, health services, policing

- Food in short supply and expensive

- Previous decades had produced many university graduates whose future expectations were now dashed

- Traditional communities were being shattered: new shanty towns and apartment blocks meant that extended families were broken up, village communities were vanishing, traditional leaders lost their authority

- “For the older people there was loss. For those young enough not to know anything of the former rural life, there was disorientation.“

Egypt’s President Sadat represented to many the worst of these changes. Sadat was opening up Egypt to the new capitalism and foreign investment that accelerated the extremes of the rich-poor divide. Middle incomes declined dramatically.

Worse still, a growing economic gap between rich and poor was accompanied by a growing cultural gap. During the riots in Cairo in 1977, favourite targets for arson and vandalism were nightclubs — of which more than three hundred opened during the decade — and luxury US made cars — of which imports had gone up fourteen times. Both were symbols of the lifestyle of an elite that was enjoying greater connection with the rest of the world, and particularly the West, but which was increasingly detached from the majority of Egyptian population. By the end of the decade, more than 30 percent of prime-time television programming was from the US, with episodes of Dallas repeated ad infinitum. Inequality was combined with a sense of cultural invasion. It was an explosive mix. (p. 28 – my bolding in all quotations)

Amidst those swayed by Western influence nationalist and socialist commitments were those who turned to their religion in various ways, some withdrawing into mysticism, for example, others looking for wider change. Islamism was spreading through the universities and professional bodies.

Islamism promised to re-establish confidence and pride and to provide a solution to the many pressing challenges now faced by tens of millions of people. (p. 28)

Jason Burke identifies this moment for the birth of the militant Islam so prominent today:

If the roots of modern Islamic militancy lie anywhere it is here: in the resurgence of Muslim faith identities and the activism of the 1970s. Throughout this crucial decade, Islamists gained support. Alongside them was the minority who called for violence to bring about revolutionary change and usher in a new, just order. (p. 28)

(See above in the side-bar Ed Husain’s childhood memories of first hearing of this movement. Note that Islamism was a relatively narrow political movement that, while growing and influencing many, did not represent the mainstream Muslim religion itself.)

Profile of those advocating violence

Those with the same goals as the Islamists of the Muslim Brotherhood but who believed in the necessity for violence:

- 27 years of age on average

- rural or small town backgrounds

- had come to Cairo to further their education, mixed with other students

- the first in their families to have the opportunity to earn a university degree

- most had fathers who were middle-ranking government employees

- most achieved very high grades

- came from stable families

- those working were in the professions: pharmacists, doctors, teachers, engineers, army officers

- better off than those in the slums

- insulated from the worst of the soaring prices

But as so often in history, those who turned to revolution

had much greater ambitions, both personally and for their country, and a keen sense of injustice. . . . they represented the ‘raw nerve’ of Egyptian society. (p. 29)

Islamism — both its nonviolent and violent forms — was spread beyond Egypt and India and could be found “from Morocco to Malaysia”, always with the same profiles, the same characteristics, the same goals and grievances.

Jason Burke portrays how it manifested itself in Iran following remarkably similar demographic and economic patterns and culminating in violence. In place of Sadat was the Shah. Saudi Arabia likewise experienced major changes and dislocations and King Faisal even made moves to open education to women. The violent would-be revolutionaries in that state did differ in their profiles from those elsewhere (their leader Juhaiman al-Utaiba was not from the urban middle class) “but their vision was similar.”

–o-0-o–

| Change is continuous, but the stresses it generates tend to accumulate, lying below the surface until eventually the earthquake comes. The broad-ranging religious revival was an explosion of social and economic tensions building up over decades. The catalyst for the explosion was a series of events: military defeats, oil-price hikes, political choices by men like President Sadat of Egypt and Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran. Equally important, though, were the ideologues who formulated and promoted the new extremist thinking. Two thinkers in particular were hugely influential, and remain so today. (p. 31) |

.

Two revolutionary ideologues

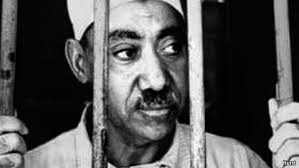

Syed Qutb, author of Milestones (pdf link — previously mentioned in How Terrorists Are Made, 2), published 1964.

Qutb’s book Milestones has been repeatedly cited as the foundational text for the entire movement of contemporary Islamic militancy.

Abdel Salam Farraj Attiya [Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj]

Author of The Neglected Obligation (link is to pdf version; variously translated The Neglected/Absent Duty/Obligation; the neglected duty was jihad in the politically violent sense and he added it as a sixth to the existing five pillars of Islam; see Islamopedia article for further details). Farraj had hoped the work would be widely read but initially his circle plotting the assassination of Sadat feared the attention it would attract from the authorities and restricted it to their narrow membership. Outside that circle the first copy was discovered by the police after the assassination of Sadat in 1981. It took Qutb’s book to the next step of enjoining the fight against other Muslims who stood in the way of restoring the ideal Islamic state.

Fawaz Gerges notes that The Neglected Obligation was the “operational manual for jihadis” in the 1980s and first half of the 1990s. (p. 254)

Qutb was hanged in 1966 and Farraj was hanged alongside Sadat’s assassins in 1982. Both their works continue to circulate widely:

in mosque bookshops in London, as PDF files on the Internet, in the libraries of religious schools in Pakistan, passed from hand to hand in militants’ dormitories in Syria and, of course, still read in the authors’ homeland. (p. 31)

Compare Ed Husain’s discoveries of Western influence on the radical thought of Islamists who had misleadingly boasted that their ideas were “pure”, free from Western influence (The Islamist, pp. 160ff.).

He found instead that the arguments derived from Hegel (the state as the instrument of God), Rousseau (criticisms of democracy), and others. Hegel, of course, also influenced Marx and Hitler is often seen as the inheritor of the thought begun with Rousseau.

“I was not, I had discovered, a believer in any distinct ‘Islamic’ political system. [The] ideas were not innovatory Muslim thinking but wholly derived from European political thought. In and of itself this was not a negative development. My objection was, and remains, the deception . . . in claiming that it was ‘pure in thought’, not influenced by kufr.” (p. 162, The Islamist)

Burke comments on the “striking influence of left-wing ideologies” on Qutb’s and Farraj’s thought. Compare the following passage from Milestones with Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto:

After annihilating the tyrannical force, whether it be in a political or a racial form, or in the form of class distinctions within the same race, Islam establishes a new social, economic and political system, in which the concept of the freedom of man is applied in practice. (p. 70 of Milestones)

These works are far from being theological treatises.

They are revolutionary tracts, ideological handbooks for a new wave of militants. Both Qutb and Farraj saw a world divided between belief and unbelief, light and darkness, peace and war, justice and tyranny, virtue and vice, corruption and purity. These divisions were stark. There was no middle ground and no room for compromise. The imperative for men on earth was to work towards the triumph of righteousness over evil and wrongdoing. (p. 32)

Qutb and Farraj were not following in the footsteps of spiritually minded imams and scholars of Islam’s past. Their ideas, their inspiration, was certainly not “a spiritual calling”. Notice what their inspiration actually was:

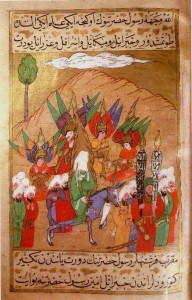

It was not a deep attraction to the principles of the Muslim faith, nor even a deep understanding of the injunctions contained within the holy texts of Islam. Instead, it was a historical example: the achievements of the Prophet Mohammed and of the first generation of his followers, the so-called Salaf. This is as true for today’s militants as it was for Qutb, Farraj and their associates in the 1960s and 70s. (p. 32)

The political circumstances of their own day along with the social and economic stresses were interpreted through the acts of Mohammed, or rather, the history of Muhammad was interpreted through the political contingencies and aspirations of these authors.

My own reflection on Burke’s analysis here leads me to compare, at least partially, the way certain fundamentalist Christians interpret the gospels and life of Jesus to justify their own love of, say, capitalism: compare the prosperity gospel. It certainly helps to clarify even further why Islamism has failed to appeal to the overwhelming majority of (more religiously minded) Muslims today. (Compare Ed Husain’s recollections of his grandfather’s Muslim religion in the first side-box above.)

In Muhammad’s early years the Arabs were divided; Mecca was a centre of commerce and idolatry. Muhammad was forced to flee to Medina when he confronted the faithlessness and consumerism of his fellows. In exile he gathered and trained followers before returning to overthrow the rulers of Mecca and to unite the Arabs in the true religion.

[This story’s] echoes in the present were hardly lost on the new wave of extremist thinkers who drew on it heavily, secure in the knowledge that it could be cited as incontrovertible historical evidence of the righteousness of their cause, particularly when contrasted with the abject failures of their current leaders.

Qutb . . . explicitly invoked the example of seventh-century Arabia when describing the Egypt of his day as plunged in jahiliyya, the chaotic, violent, tyrannical ‘ignorance’ that prevailed before the time of Mohammed . . . (p. 33)

Burke points out, furthermore, that Qutb wrote in the everyday language of the commoner and not in the abstruse style of the Islamic scholars.

Qutb called for a “return” to the original purity of the first Muslims:

If Islam is again to play the role of the leader of mankind, then it is necessary that the Muslim community be restored to its original form. It is necessary, to revive that Muslim community which is buried under the debris of the man-made traditions of several generations, and which it crushed under the weight of those false laws and customs which are not even remotely related to the Islamic teachings. . . . .

How is it possible to start the task of reviving Islam? It is necessary that there should be a vanguard which sets out with this determination and then keeps walking on the path, marching through the vast ocean of Jahiliyyahh which has encompassed the entire world. (pp. 25, 27 of Milestones)

Islam has no authoritative priesthood or equivalent of a papal authority but it does have long tradition of scholars who have been especially trained in their texts and who are widely respected as having the wisdom to guide Muslims in how to adapt their practices to their changing world. Qutb and Farraj had no such religious training and they rejected the privileged status of these scholars.

This rejection of the authority of the scholars so many of whom had been carefully co-opted by state authorities, was genuinely revolutionary. If an individual had no responsibility to obey those who traditionally held power over a community, activism of a very new kind became legitimate. (p. 34)

Where to start?

Shukri Mustafa chose to follow Muhammad’s example by withdrawing to a cave in the desert with a following of hundreds. His efforts came to an end in a confrontation with government forces after his group kidnapped a government minister.

Others chose to follow Muhammad’s later example and attempt to directly overthrow the Egyptian government in a coup. Though the 1974 attempt failed the leaders, Burke notes, were encouraged knowing that their efforts would nonetheless inspire others to follow. And they did — with the assassination of Sadat in 1981.

Why the West?

We heard often in the news in the 70s and 80s of terrorists and aircraft hijackers attacking targets affecting the West, including the Olympics, but the groups who are the subject of this post were not nationalists and were not interested in targeting the West. They were focused on a restoration of an ideal Islamic state. Sadat was not assassinated so much because of his initiative to make peace with Israel: his assassins instead likened him to the pagan and tyrannical Pharaohs of ancient Egypt.

Burke sees the initial focus on the West coming to fruition with the Iranian revolution that overthrew the Shah in 1979. Ayatollah Khomeini outdid the appeal of left-wing ideologies in mobilizing the urban poor.

He did this partly by articulating many Iranian’s fear of Western cultural invasion with a savage brilliance. His success in instigating revolution in 1979 lent powerful credibility to his arguments, and rapidly the stock phrases of his newly triumphant Iranian Islamists — terms like the ‘Great Satan’, ‘Westoxification’ and the ‘Crusader-Zionist alliance’ — entered everyday vocabulary across the Islamic world. (p. 35)

Then came Iran’s war with Iraq and no further leadership came from Iran in directing wider animosities against the West.

About the same time Russia invaded Afghanistan and a new theatre for the mujahideen opened. Afghanistan proved to be the crucible of Islamist extremists who turned their attention from “the near enemy” to “the far enemy”. And that’s where the stories of today begin.

The father of global jihad

This brings us to the next chapter in Jason Burke’s study. In brief, the Afghan war pitted Muslims against a great atheist power and the call went out for Muslims from everywhere to come to assist. Here another key person enters the stage: Abdullah Azzam, the “father of global jihad”.

Where Qutb and Farraj set their sights on combating “the near enemy” in their homelands, the charismatic orator Azzam spoke of two forms of jihad, both violent (unlike other meanings of jihad in the Koran). His written argument went by the unwieldy title of Defending the lands of the Muslims is each man’s most important duty (truncated in the online text.) For Azzam there was offensive jihad, a requirement to attack enemies even though they post no immediate threat to Muslims; and defensive jihad, the requirement to attack all power threatening or occupying Muslim territory.

The former (offensive) jihad was the responsibility of the state; the latter (defensive) was the obligation of every Muslim regardless of any state orders.

Muslims flocked to the call of “defensive jihad” from not only the Middle East, but from west Africa, China and east Asia. They flocked first to Peshawar in Pakistan where they supposedly prepared for war and exchanged ideas. In fact, however, only a small fraction would actually go into the battle zones. Most remained in Peshawar doing humanitarian support work. What was more empowering for future movements than the limited battle experience of the mujahideen was the myth that followed in their wake: the myth that thousands of Muslims had answered the call to defend Muslims against a great Satanic power, had fought that power and won! They were also, and this was another action of special significance for the future, building networks through personal relationships. Muslims unable to go to Pakistan/Afghanistan were also captured by the idea of supporting a great atheist power against a Muslim land. One question that might have been raised was “After Afghanistan, then . . . ?” Azzam’s inspired the idea that defensive jihad was the responsibility of all Muslims to free all lands that had ever once been Muslim.

Azzam’s argument at the time of the Afghan war would transform the entire extremist movement. The global community of Muslims he envisaged would be one where all fought for each other, across the planet. It was a call to arms that resonated throughout the Muslim world. (p. 39)

Yet to be added . . . .

the background to Osama bin Laden’s view of jihad; and especially the role of Saudi Arabia in promoting a certain strand of Islam. . ..

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In part of course, recent Muslim radical attacks began specifically in France, after French warplanes took an active role in bombings in North Africa. And especially attacks on Syria. This does not justify the radical attacks, of course. But it does show how response and countermeasure, escalate things.

Leila Khaled not allowed to return to her homeland because its now “israel.” I find it revolting you deem her an Islamic terrorist. You may as well classify the largest/longest suffering refugee population all terrorists then. Though not all are Muslim.

DFLP one of several organizations associated with the Palestine Liberation … founded by an Orthodox Christian, Nayif Hawātmeh.

PFLP grew out of the Harakat al-Qawmiyyin al-Arab, or Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), founded in 1953 by Dr. George Habash, a Palestinian Christian

Even the PLO counts Christians among its founders and Dr Hanan Ashwari is currently a PLO Executive member.

Please, please, DO READ what I write. I do NOT, repeat NOT, deem Leila Khaled an Islamic terrorist. In fact I introduce her (following Jason Burke) to show that the earlier generation of terrorists were NOT Islamic terrorists!)

The very names Leila Khaled and Carlos the Jackal stand in opposition to the very idea of “Islamic terrorism”. The names are introduced to demonstrate that Islamic terrorism is a new development since their time!

Justice (or injustice) is a powerful motivating factor—its expression may be religious or non-religious—the emotional appeal of striving towards justice is strong in humanity….(…or at least in decent human beings)

An environment that has the mechanism to address this desire for justice will have more chances of peaceful resolution than an environment that lacks such a mechanism.

(therefore… “Islamists” who advocate for the rule of law (any law) may offer a way to offset those who advocate for violence….because if given an alternative to have a peaceful resolution or a violent one—most decent human beings are going to choose the peaceful alternative.)

Rejection of the authority of the scholars—could be traced to when the Ottomans began to “Modernize” during the tanzimat reforms. The reason that these scholars (Jurists) had “authority” in the Muslim community was because they were perceived as a force independent of the state/executive power and so could stand in opposition to it as a restraining force…and the state could also act as a balancing force to any abuse of power by the jurists/scholars. But in modern nation-states—the state legislates law. The legislature is part of the power structure along with the executive/administrative. Some types of “secularism” further erodes the diffusion of power—and instead helps to centralize it, so that now you could have laws made by the ignorant for the ignorant!…which is why “Sharia” today ends up in a mess…..

However—despite this, Muslim scholars do hold authority/legitimacy for most Muslims and when they condemn terrorism—this is heard by Muslims. But—in order to retain this legitimacy Muslims scholars need to retain their sophistication, nuance and consistency—so all forms/types of terrorism have to be condemned….if they appear selective—the way the West often appears—they may be perceived as inconsistent in their moral principles.

The future—Transnational “jihadism” (as a Muslim, to use “jihad” for this purpose feels very wrong) has come about and there are consequences. What could have been contained as “nationalist” struggle for territorial integrity now is a transnational goal for something undefinable called an “Islamic State”. Along with this is the other phenomenon of Islamophobia which has created an environment that pushes towards solidarity among the global Muslim community. This is all occurring in an internet age which facilitates globalization and this phenomenon (globalization) in turn erodes the strength of national identity-constructs (Which is why many countries have movements such as Pegida, EDL, Reclaim Australia and various other pro nationalist/anti Muslim movements….) To top it off—as war continues, failed states are growing…and in areas where there are Muslims…..As a Muslim privileged enough to live outside the conflict zone—I have the luxury to reflect—and I cannot help but think change is inevitable…..?……

In other words, you are following in the tradition of the path set out in Milestones by Qutb and support militant Islamism (though not terrorism or violence, of course, because you see those tactics as counterproductive to achieving your goals).

You do not understand how the separation of powers works in a western democracy (perhaps you are taking your information from Islamist literature?). The judiciary and legislative branches are not part of the one power but are separate — as we have seen in Australia when even legislators have at times been taken to the judiciary by the executive (police) powers, tried, and jailed.

In countries like Malaysia we know that the there is no true separation of powers – and that political corruption allows the legislators and/or executive to use the judiciary for their own ends, but public pressure and freedom of information keeps that from happening in places like Australia to anything like the serious extent we see it happen in various Asian countries.

I do not support militant Islamism—but “Islamism” that promotes ethical, transparent and just rule of law is better for peace and progress of a society—-and prevents militancy….

Islamism is against everything a truly democratic state with separation of powers stands for.

Western democracy may be working fine in the West—or Australia—but I do not live there

In the West when it is not working properly we have a history of organizing public action to get things right again — we don’t call on the priests or imams to come in. We take responsibility and in the process we make sure all religions — including Muslims — have the same rights and freedoms.

organizing public action—would be Jihad—and Muslims who argue for public actions—-are “Islamists” in your vocabulary….So it is ok for western/secular Jihadis to organize and work to reduce the injustice of their political system—but Muslims should not do so—right!!!

It is ok for westerners to promote “Universal principles” as long as they are labeled “secular”—but even if those very same principles are promoted by others—they are not ok if they have any other label than “secular”…so Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist “Universal” principles of freedom, equality and justice are not ok simply because the language they use is different from what the “West” is used to?—That is a very intolerant—very “Wahabi” attitude to have…..

Islam goes further in its conception of freedom than the “West”. It allows people to retain their identities in the Public sphere without having to “hide” it in some kind of “neutrality”. It is pluralistic and respects the right to identity of all religions/philosophies. Under such a system—different peoples can live fully under their own laws that they voluntary give assent to.

Here is a perspective for pluralism–http://tariqramadan.com/english/2015/09/29/article-on-celyon-today-pluralism-and-its-contemporary-challenges-24092015/

Islam also goes further than “Secularism”—that is, if we understand the intent of secularism as a balance of power—then the Islamic system does a better job at this by separating the law from “state”

If the citizens in the West do have power—than how does one explain the injustices, the exploitation, the corruptions, the abuse of power and privilege, the oppression of the marginalized?—do we say that the all-powerful western citizens, who did nothing about this—are morally bankrupt….?…..the West has had the time to work on their “secularism” for what?…about 200 years?—and you guys still haven’t got it right!!!…yet you want everyone else to adopt such an inadequate system?

I think it is time to ditch Secularism and go for Pluralism—-it is a better concept for the future….After all—it was this very reasoning that made the West ditch their Christian past wasn’t it?

Right, there is no place for Muslims to try to change society “as a Muslim program” as distinct from a purely secular democratic program and to try to set up laws that claim to be “above the state” — that’s the sort of tyranny that the West has struggled to fight its way out of. We don’t want to be sucked right back into another round of the same.

In the same way there is no place for any religious or ethnic group to change society “as that group” to mould society according to its own “superior” values.

All Muslims and religions and ethnic groups can work as one on a secular program to guarantee the rights of all — that your Islamism would deny if you are honest about it.

And I don’t believe you when you say your Islamist laws are exactly the same as the UDHR or superior. They are not. Trying to say they are is a dishonest pretence. We have seen the same before too many times with our own religious activists. We’ve been there, done that — cost too much blood and suffering — and have no wish to return.

You have not listened or understood a word I have said about our Western systems because, presumably, you are too indoctrinated by your Islamist teachings. The corruption in the West is nothing compared with the corruption in most Muslim nations and in the reason for that is that we are actually working to fight it when we identify it and we have systems to jail even politicians and leading CEOs who are found to be corrupt.

Come and visit Australia and get to know us for a while and learn for yourself — and don’t just mindlessly swallow what you read in your Milestones and other Islamic propaganda. Where do you think HRW and AI come from? Who are the biggest supporters of those? Where else do you find the public campaigning and winning to get rights for indigenous peoples, for gays, for women, for children — You reject the UDHR and pretend to say you have better standards.

Name one value that your Islamism wants to see that is not already found in a viable secular democracy. Everything you say you want to see is what we already have. You speak of corruption but don’t see that the corruption is far less in secular democracies than in Muslim countries — and you especially fail to see that secular democracy works, and corruption is constantly being challenged, because of our values and system.

You even confuse secular democracy with capitalism not realizing how many Westerners are working for a better alternative. Your Islamist propaganda does not tell you the whole story, you know. And telling a half truth can sometimes be a bigger lie doing more harm than any other kind of falsehood.

You preach the same idealism and “reason” and “superior ways” that has littered history with bloodshed and barbarity so many, many times before. Of course you don’t believe that — but those of us who know history can see you setting out on exactly the same sort of path in exactly the same sort of way that others have taken so often.

In utopias like the one you seek there are always idealists who really believe they would never do anyone any harm, but they are always, always, forced to compromise or are swept aside by those who see the need for violence for the new society to hold on to power. That is the reality and Islamists are no better or worse than the rest of humanity, and what they offer is no more idealistic than other visions, and it is their hubris if they think otherwise.

A proper democracy (western or not) with functioning ‘trias politica’ also needs:

* Educated populace – ~14 years of education should be minimum requirement for everyone.

* Informed populace – independent free press, no media monopolies

* Pluralistic politics – in short, parties transcend religious/ethnic divides

And a sane constitution to protect these foundations.

One can try without one or even all of them, but it will be an unstable uphill battle, more so in the instant communication world of today. Instability also tends to increase if those foundations aren’t kept up.

Reading this reminds me a bit of reading Josephus and his explanations for the Jewish war with Rome…

One might easily misinterpret “The establishment of the state of Israel, now recognized by the international community after a bloody war……:.

It would be clearer to say that “when the international community had recognized the state of Israel, then the Arab countries started a bloody war……”.

That’s not what I read in Benny Morris’s 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. The pro-Israel Jewish historian informs readers that Ben Gurion and party never agreed to accept the borders the UN General Assembly voted on 29 November 1947 by 33 to 10 with 13 abstentions to be the terms of partition. Civil War within Palestine followed. On 14th May 1948, late afternoon, Ben Gurion declared the State of Israel into existence and within minutes President Truman, contra his own State Department, declared de facto recognition, and a few hours later (midnight) the Arab attack began.