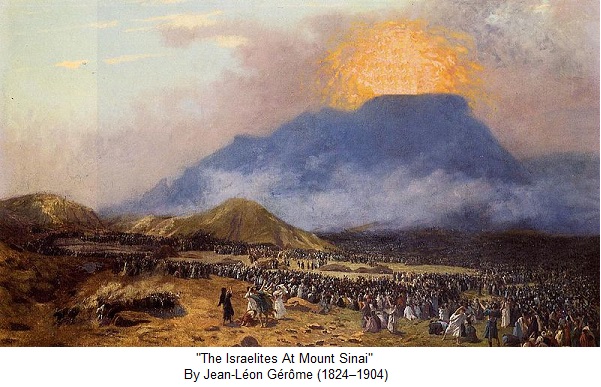

After reading Jan Assmann’s Moses the Egyptian I’d like to set out here the various alternative versions of the story of Moses and the Exodus as written by ancient Greek and Egyptian historians. (These will be known to many readers but I want to have them all set out together and perhaps discuss their significance in relation to “what really happened” afterwards.)

Here is the apparently earliest non-Jewish record, written by the Greek Hecataeus of Abdera in the fourth and third centuries B.C.E. after he settled in Egypt. It comes to us via another Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus [= of Sicily] of the first century B.C.E. I will highlight significant sections that overlap (however obliquely) with the biblical narrative.

[3] Since we are about to give an account of the war against the Jews, we consider it appropriate, before we proceed further, in the first place to relate the origin of this nation, and their customs.

In ancient times a great plague occurred in Egypt, and many ascribed the cause of it to the gods, who were offended with them.

For since the multitudes of strangers of different nationalities, who lived there, made use of their foreign rites in religious ceremonies and sacrifices, the ancient manner of worshipping the gods, practised by the ancestors of the Egyptians, had been quite lost and forgotten.

2 Therefore the native inhabitants concluded that, unless all the foreigners were driven out, they would never be free from their miseries. Continue reading “Moses and the Exodus According to the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians: Hecataeus”