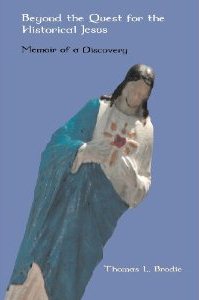

My copy of Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus happily arrived today. I have a few other posts in the pipeline waiting final editing so that will give me a little time to prepare discussing some aspects of this new book here.

My copy of Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus happily arrived today. I have a few other posts in the pipeline waiting final editing so that will give me a little time to prepare discussing some aspects of this new book here.

Meanwhile, here’s the back cover blurb, also found on the Amazon site — here with my own highlighting and formatting:

In the past forty years, while historical-critical studies were seeking with renewed intensity to reconstruct events behind the biblical texts, not least the life of Jesus, two branches of literary studies were finally reaching maturity.

- First, researchers were recognizing that many biblical texts are rewritings or transformations of older texts that still exist, thus giving a clearer sense of where the biblical texts came from;

- and second, studies in the ancient art of composition clarified the biblical texts’ unity and purpose, that is to say, where biblical texts were headed.

The primary literary model behind the gospels, Brodie argues, is the biblical account of Elijah and Elisha [My post on Brodie’s earlier book making this case is at The Elijah-Elisha narrative as a model for the Gospel of Mark], as R.E. Brown already saw in 1971. In this fascinating memoir of his life journey, Tom Brodie, Irishman, Dominican priest, and biblical scholar, recounts the steps he has taken, in an eventful life in many countries, to his conclusion that the New Testament account of Jesus is essentially a rewriting of the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible, or, in some cases, of earlier New Testament texts. Jesus’ challenge to would-be disciples (Luke 9.57-62), for example, is a transformation of the challenge to Elijah at Horeb (1 Kings 19), while his journey from Jerusalem and Judea to Samaria and beyond (John 2.23-4.54) is deeply indebted to the account of the journey of God’s Word in Acts 1-8.

The work of tracing literary indebtedness and art is far from finished but it is already possible and necessary to draw a conclusion: it is that, bluntly, Jesus did not exist as a historical individual.

This is not as negative as may at first appear. In a deeply personal coda, Brodie begins to develop a new vision of Jesus as an icon of God’s presence in the world and in human history.

And just one more tidbit for now — the second paragraph of Brodie’s Prefatory Introduction: Continue reading ““Jesus did not exist as an historical individual”: Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus”