Let’s stay on detour from our Why People Believe in Gods series of posts for another moment . . . .

Returning to that earlier quotation of James Q. Wilson, here it is in full (the bolded highlighting is my own) . . . .

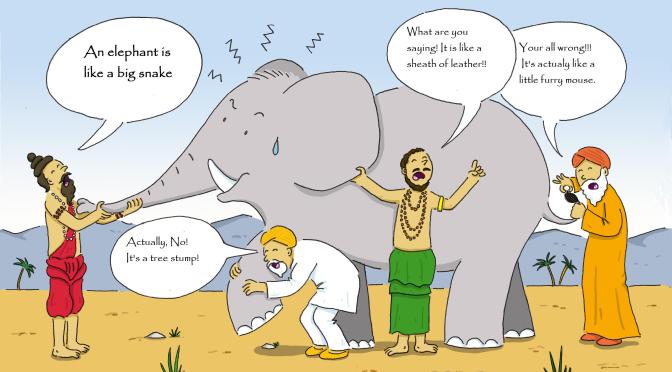

To find what is universal about human nature, we must look behind the rules and the circumstances that shape them to discover what fundamental dispositions, if any, animate them and to decide whether those dispositions are universal. If such universal dispositions exist, we would expect them to be so obvious that travelers would either take them for granted or overlook them in preference to whatever is novel or exotic. Those fundamental dispositions are, indeed, both obvious and other-regarding: they are the affection a parent, especially a mother, bears for its child and the desire to please that the child brings to this encounter. Our moral senses are forged in the crucible of this loving relationship and expanded by the enlarged relationships of families and peers. Out of the universal attachment between child and parent the former begins to develop a sense of empathy and fairness, to learn self-control, and to acquire a conscience that makes him behave dutifully at least with respect to some matters. Those dispositions are extended to other people (and often to other species) to the extent that these others are thought to share in the traits we find in our families. That last step is the most problematic and as a consequence is far from common; as we saw in the preceding chapter, many cultures, especially those organized around clans and lineages rather than independent nuclear families based on consensual marriages and private property, rarely extend the moral sense, except in the most abstract or conditional way, to other peoples. The moral sense for most people remains particularistic; for some, it aspires to be universal.

Because our moral senses are at origin parochial and easily blunted by even trivial differences between what we think of as familiar and what we define as strange, it is not hard to explain why there is so much misery in the world and thus easy to understand why so many people deny the existence of a moral sense at all. How can there be a moral sense if everywhere we find cruelty and combat, sometimes on a monstrous scale? One rather paradoxical answer is that man’s attacks against his fellow man reveal his moral sense because they express his social nature. Contrary to Freud, it is not simply their innate aggressiveness that leads men to engage in battles against their rivals, and contrary to Hobbes, it is not only to control their innate wildness that men create governments. Men are less likely to fight alone against one other person than to fight in groups against other groups. It is the desire to earn or retain the respect and goodwill of their fellows that keeps soldiers fighting even against fearsome odds, leads men to accept even the most distorted or implausible judgments of their peers, induces people to believe that an authority figure has the right to order them to administer shocks to a “student,” and persuades many of us to devalue the beliefs and claims of outsiders. Continue reading “Another Interlude with Morality — Why Moral Beings Can Be Brutes”