Anyone following biblical studies on the web soon learns that there are some scholars who fear the potential of the internet. Anyone following certain scientists with larger than average egos also soon learns that some of them, too, don’t like what damage the web can do to their influence. And anyone attempting to engage in a scholarly or professional manner with political and social viewpoints that are very controversial in some quarters soon learns that some people cannot handle a truly free exchange of ideas and information.

Everybody, but scholars especially, should welcome the full potential of knowledge sharing that the internet has made possible. The Open Access movement can be said to have begun with the Budapest declaration of 2002:

By “open access” to this literature, we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited.

What is the point of OA?

An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarly journals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge. The new technology is the internet. The public good they make possible is the world-wide electronic distribution of the peer-reviewed journal literature and completely free and unrestricted access to it by all scientists, scholars, teachers, students, and other curious minds.

One might also argue that those who have had the privilege of higher learning have a responsibility to others in society. How can anyone justify keeping knowledge that has a public benefit away from the public, or how can one justify setting up hurdles to leap in order to access it?

Another benefit of OA is that it has the potential to keep researchers and academics generally just a little more accountable and honest. Surely most academics would presume that anything that works at increasing the appearance of public accountability is a good thing. Why would any object?

This is where we also enter the realm of free discussion. It is clear that too many scholars are not at all comfortable with defending their views in a public arena unless it is filled with sympathetic supporters of their ideas. The excuse sometimes given is that there are “trolls” out there, and time-wasters, and all sorts of problem commenters. Yup, there are. But that’s the beauty of the web — each of us has the ability to ban/delete etc the undesirables. Unfortunately too many researchers define undesirables so broadly as to include serious critics. Biblical studies seems far more than some other disciplines to be populated with scholars who are more interested in a form of evangelizing their own biases than in engaging seriously with critical discussion.

Some scholars are very stuck in an elitist pre-web mentality. They scoff at Wikipedia as a source when they could quite easily make a correction to an article they find in error. Do they despise the idea of getting their fingers dirty by engaging in a democratic sharing of knowledge?

They scoff at the bizarre ideas found “out there” — forgetting, it seems, that what they read on the internet are the same sorts of “bizarre ideas” that have always been in the public domain. Some of them even viciously insult those who remain committed to ideas and beliefs that they themselves once held before they learned better. They seem to forget, some of them, how lucky they have been to have been in the circumstances that allowed them to know better, to acquire a superior education. Does not such luck and privilege bring a responsibility with it? Not all seem to think so, unfortunately. Perhaps they believe they have had no luck or privilege at all but have worked and sacrificed hard to achieve their good fortune. If so, they still have more to learn, like how lucky they have been to have had the genes, the make-up from birth or environment, the opportunities, to apply such effort so successfully.

Added later….

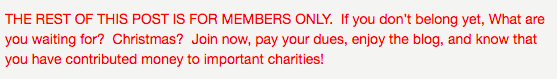

(One prominent scholar has placed a different kind of hurdle to leap for anyone wanting to hear him air his views on his professionally developed blog. One is obliged to donate to a charity of his choosing. That, too, is another elitist technique that functions to filter out those less likely to disagree with his view or at least risk offending him; it is also a barrier to all but the more affluent who have the means to donate to charities above and beyond what they already do. (I say that on the basis of my past experience in collecting for charities: many of us who have done that sort of work door to door learn that it is often the poorest who are the biggest givers.) Perhaps Bart Ehrman thinks the minimal amounts he is asking are hardly onerous. I guess that’s true for many Americans.

Does Bart really think his own approach is one that others should follow — so that everyone would have to be paying every time they want to tap in to a more privileged person’s learning?

Sorry, but Bart Ehrman would do everyone a greater service if he joined up with the open access movement and accepted the public responsibility that comes with (educational) privilege.

Like this:

Like Loading...