I will continue writing posts in response to Thomas Schmidt’s Josephus and Jesus, New Evidence so this post is a quick interjection before I have the time to write more fully about another Jesus hypothesis that appears to be being widely discussed at the moment — the hypothesis that Jesus was an anti-Roman rebel, a seditionist, in particular, the following book:

I will continue writing posts in response to Thomas Schmidt’s Josephus and Jesus, New Evidence so this post is a quick interjection before I have the time to write more fully about another Jesus hypothesis that appears to be being widely discussed at the moment — the hypothesis that Jesus was an anti-Roman rebel, a seditionist, in particular, the following book:

- Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando. 2023. They Suffered under Pontius Pilate: Jewish Anti-Roman Resistance and the Crosses at Golgotha. Fortress Academic.

(We met Fernando Bermejo-Rubio as recently as my last post, by the way, where I examined his citational support for Josephus writing a negative passage about Jesus.)

The reason I am jumping in early at this time is to flesh out (just a little) some responses I have made in discussions relating to other posts. It’s been a long time since I posted about historical methods, especially as they relate to Jesus, so consider this a brief reminder or recap.

Bermejo-Rubio repeats a common assumption:

As Justin Meggitt has rightly observed, “to deny his existence based on the absence of such evidence, even if that were the case, has problematic implications; you may as well deny the existence of pretty much everyone in the ancient world.”

I responded to Justin Meggitt’s claim back in 2020. It is available here:

Evidence for Historical Persons vs Evidence for Jesus

A few of my other posts addressing the same question of how we know about ancient persons and whether the evidence for Jesus is comparable to anyone else:

- How do we know anyone existed in ancient times? (Or, if Jesus Christ goes would Julius Caesar also have to go?)”

- Comparing the evidence for Jesus with other ancient historical persons

- Jesus Is Not “As Historical As Anyone Else in the Ancient World”

- How do we know any ancient person existed?

- Chart of mythical and historical persons — with explanations

- Historical Research: The Basics

- Doing History: How Do We Know Queen Boadicea/Boudicca Existed?

- The Quest for the Historical Hiawatha — & the historical-mythical Jesus debate

- Did the ancient philosopher Demonax exist?

- Did Aesop Exist?

- Here’s How Philosophers Know Socrates Existed

- Was Socrates man or myth? Applying historical Jesus criteria to Socrates

- Is it a “fact of history” that Jesus existed? Or is it only “public knowledge”?

- The Clueless Search for the Historical Jesus

- One Difference Between a “True” Biography and a Fictional (Gospel?) Biography

- The Historical Jesus and the Demise of History, 1: What Has History To Do With The Facts?

- The Historical Jesus and the Demise of History, 2: The Overlooked Reasons We Know Certain Ancient Persons Existed

- Historical Facts and the very UNfactual Jesus: contrasting nonbiblical history with ‘historical Jesus’ studies (I think this was my very first foray into this debate.)

And a lot more are listed here:

When Historical Persons are Overlaid with Myth

Other statements by Bermejo-Rubio that struck me as misguided:

After all, although some biographies of ancient historical characters such as Alexander the Great and the emperor Augustus contain quite a few mythical elements in their framework, it does not justify our disputing in principle the historicity of the characters themselves . . .

That point is answered in the above posts. When historical figures are overlaid by others — and even by themselves — with mythical trappings (e.g. Alexander as Dionysus, Hadrian as Hercules), we can see clearly where the real human is distinct from the mythical propaganda image.

Inconsistencies and Incongruities are a Common Element among Mythical Figures

Another:

Had Jesus been a construct created out of whole cloth, the accounts about him would presumably have been far more homogeneous. The fact that our sources are systematically inconsistent and are riddled with incongruities is better explained if we assume that a real character on the stage of history was modified in the later tradition.

Quite the contrary. It is real historical figures that emerge with fair measures of consistency; it is the mythical characters who are riddled with contradictions and incongruities. In fact it is the inconsistencies that are part of the enticing mystery and allure make such figures so attractive and believable! See

- How Mythic Story Worlds Become Believable (Johnston: The Greek Mythic Story World)

- Why Certain Kinds of Myths Are So Easy to Believe

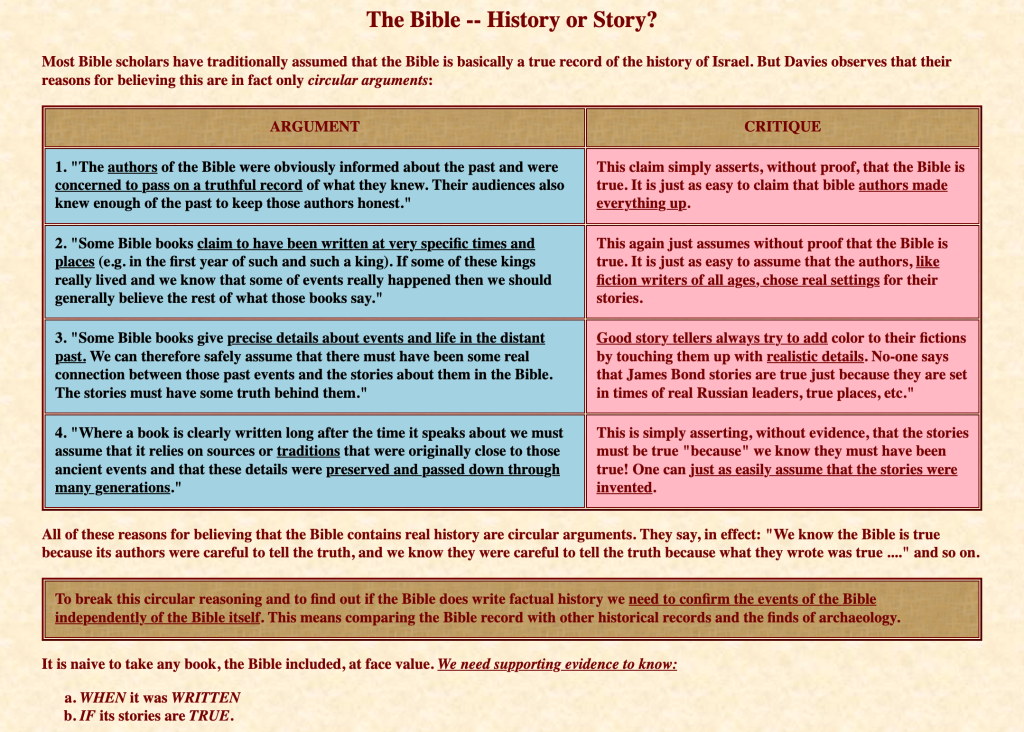

And one page that sums it all up in a simple table:

- The Bible — History or Story? — where I sum up the error at the base of so much biblical studies by distilling the main points of Philip Davies pivotal publication.

But for now — back to work on some other aspects of Thomas Schmidt’s argument for Josephus making a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Christian origins. . . .

But for now — back to work on some other aspects of Thomas Schmidt’s argument for Josephus making a valuable contribution to our knowledge of Christian origins. . . .

(By the way — questions of historicity and authenticity do arise in classical studies, too. I look forward to posting a few instances and comparing how they are approached by ancient historians and scholars with a primary focus on biblical studies.)