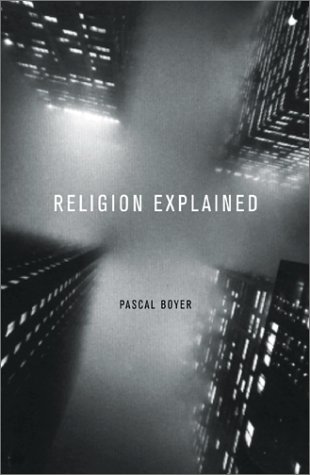

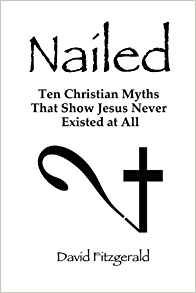

Not long ago PZ Myers responded positively to certain arguments in the post by Tim O’Neill, Jesus Mythicism 3: “No Contemporary References to Jesus”. PZ was not to know of the presumably inadvertent misrepresentations Tim O’Neill made of David Fitgerald’s arguments in that post. In a followup post by PZ, Tim reminded readers that he had, he believed, demonstrated the incompetence of David’s arguments.

Not long ago PZ Myers responded positively to certain arguments in the post by Tim O’Neill, Jesus Mythicism 3: “No Contemporary References to Jesus”. PZ was not to know of the presumably inadvertent misrepresentations Tim O’Neill made of David Fitgerald’s arguments in that post. In a followup post by PZ, Tim reminded readers that he had, he believed, demonstrated the incompetence of David’s arguments.

It’s not enough to demonstrate a silence in some sources – you have to show that any of these sources SHOULD have mentioned Jesus. This is where Fitzgerald and his ilk fail every time. I discuss this at length here:

https://historyforatheists.com/2018/05/jesus-mythicism-3-no-contemporary-references-to-jesus/

Now I am sure Tim is convinced of his sincerity and genuinely believes that his criticism of David’s arguments are entirely just and reasonable. I also think that the emotive language Tim so often uses betrays an emotional investment in his viewpoints that blinds him from his bias and accordingly from noticing details in David’s book that contradict his (Tim’s) perceptions (better, pre-perceptions).

A few examples follow. (Not many. To do an exhaustive review — as I did for Daniel Gullotta’s review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus in a leading journal dedicated to the study of the historical Jesus — would not be healthy for my emotional well-being, but at the same time I am quite willing to take the time to respond to any particular claims made by Tim that readers might think do carry genuine critical weight. The reason I post at all this response at all is because, well, I don’t like to see misrepresentations stand without challenge.)

I first address Tim’s criticism of David’s argument concerning Seneca’s silence concerning Jesus. It will be useful, first, though, to read the passage by David that Tim criticizes. Here is David’s section on Seneca:

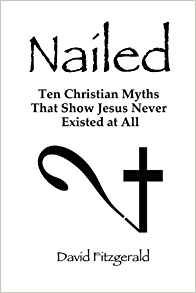

Seneca the Younger (c. 3 B.C.E. – 65) Lucius Annaeus Seneca, Stoic philosopher, writer, statesman, and de facto ruler of the Empire for many years, had three compelling reasons to mention Jesus at least at some point in his many writings.

- First, though regarded as the greatest Roman writer on ethics, he has nothing to say about arguably the biggest ethical shakeup of his time.

- Second, in his book on nature Quaestiones Naturales, he records eclipses and other unusual natural phenomena, but makes no mention of the miraculous Star of Bethlehem, the multiple earthquakes in Jerusalem after Jesus’ death, or the worldwide (or at the very least region-wide) darkness at Christ’s crucifixion that he himself should have witnessed.

- Third, in another book On Superstition, Seneca lambasts every known religion, including Judaism.1 But strangely, he makes no mention whatsoever of Christianity, which was supposedly spreading like wildfire across the empire. This uncomfortable fact later made Augustine squirm in his theological treatise City of God (book 6, chapter 11) as he tried mightily to explain away Seneca’s glaring omission.

In the 4th century, Christian scribes were so desperate to co-opt Seneca they even forged a series of correspondence between Seneca and his “dearest” friend, the Apostle Paul!

(Nailed! p. 34 – my formatting)

David Fitzgerald is addressing throughout his book the views of Christian believers, those who believe the gospel narratives about Jesus. For example:

In the case of Jesus, his believers are left with two unhappy choices:

- either the Gospels were grossly exaggerating Jesus’ life and accomplishments, and Jesus was just another illiterate, wandering preacher with a tiny following, completely unnoticed by society at large –

- or he was an outright mythical character.

(Nailed! p. 43 — again, my formatting)

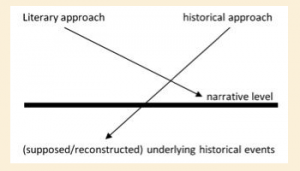

At no point in any of David’s discussions of the various silences can I see him saying that any particular silence somehow “means Jesus did not exist”. Notice his conclusion above. David concludes that the cumulation of certain silences in certain contexts leads to a number of “unhappy choices” for believers in the gospels: one of these is that Jesus was indeed what many historical Jesus scholars claim, that he was “just another wandering preacher with a tiny following, completely unnoticed by society at large.” We will see the significance of this point by David when we come to Tim’s criticism.

David made the focus of his argument clear from pages 14 and 15 of the opening chapter of his book:

The supposed historical underpinning of Jesus, which apologists insist differentiates their Christ from the myriad other savior gods and divine sons of the ancient pagan world, simply does not hold up to investigation.

On the contrary, the closer we examine the official story, or rather stories, of Christianity (or Christianities!), the quicker it becomes apparent that the figure of the historical Jesus has traveled with a bodyguard of widely accepted, seldom examined untruths for over two millennia.

The purpose of this all-too-brief examination is to shed light on ten of these beloved Christian myths, ten beautiful lies about Jesus:

1. The idea that Jesus was a myth is ridiculous!

2. Jesus was wildly famous – but there was no reason for contemporary historians to notice him…

3. Ancient historian Josephus wrote about Jesus

4. Eyewitnesses wrote the Gospels

5. The Gospels give a consistent picture of Jesus

6. History confirms the Gospels

7. Archeology confirms the Gospels

8. Paul and the Epistles corroborate the Gospels

9. Christianity began with Jesus and his apostles

10. Christianity was a totally new and different miraculous overnight success that changed the world!

(my bolded emphasis)

Notice. David has chosen to address the myth that Jesus was wildly famous! David is arguing that the miraculous stories surrounding Jesus that so many Christians believe in have no basis in the historical record, despite what too many apologists (he mentions Josh McDowell and Douglas Geivett) assert.

Tim appears to have overlooked this point, purpose, target of David’s discussion about the silence of Seneca. I have bolded the sections that directly conflict with David’s actual argument as set out above. Continue reading “Fake History for Atheists”

Like this:

Like Loading...