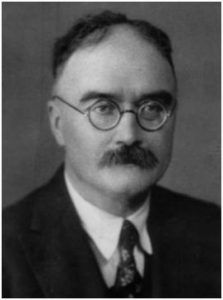

His mother is a virgin and he’s reputed to be the son of a god; he loses favor and is driven from his kingdom to a sorrowful death—sound familiar? In The Hero, Lord Raglan contends that the heroic figures from myth and legend are invested with a common pattern that satisfies the human desire for idealization. Raglan outlines 22 characteristic themes or motifs from the heroic tales and illustrates his theory with events from the lives of characters from Oedipus (21 out a possible 22 points) to Robin Hood (a modest 13). A fascinating study that relates details from world literature with a lively wit and style, it was acclaimed by literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman as “a bold, speculative, and brilliantly convincing demonstration that myths are never historical but are fictional narratives derived from ritual dramas.” This book will appeal to scholars of folklore and mythology, history, literature and general readers as well. (Blurb from online edition of The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama by Lord Raglan)

His mother is a virgin and he’s reputed to be the son of a god; he loses favor and is driven from his kingdom to a sorrowful death—sound familiar? In The Hero, Lord Raglan contends that the heroic figures from myth and legend are invested with a common pattern that satisfies the human desire for idealization. Raglan outlines 22 characteristic themes or motifs from the heroic tales and illustrates his theory with events from the lives of characters from Oedipus (21 out a possible 22 points) to Robin Hood (a modest 13). A fascinating study that relates details from world literature with a lively wit and style, it was acclaimed by literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman as “a bold, speculative, and brilliantly convincing demonstration that myths are never historical but are fictional narratives derived from ritual dramas.” This book will appeal to scholars of folklore and mythology, history, literature and general readers as well. (Blurb from online edition of The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth, and Drama by Lord Raglan)

The 22 typical incidents in mythical tales

(1) The hero’s mother is a royal virgin;

(2) His father is a king, and

(3) Often a near relative of his mother, but

(4) The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

(5) He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

(6) At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather, to kill him, but

(7) He is spirited away, and

(8) Reared by foster-parents in a far country.

(9) We are told nothing of his childhood, but

(10) On reaching manhood he returns or goes to his future kingdom.

(11) After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast,

(12) He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor, and

(13) Becomes king.

(14) For a time he reigns uneventfully, and

(15) Prescribes laws, but

(16) Later he loses favour with the gods and/or his subjects, and

(17) Is driven from the throne and city, after which

(18) He meets with a mysterious death,

(19) Often at the top of a hill.

(20) His children, if any, do not succeed him.

(21) His body is not buried, but nevertheless

(22) He has one or more holy sepulchres.

The first thing that needs to be clear is that Lord Raglan has drawn these parallel motifs from what he terms “genuine mythology” — meaning “mythology connected with ritual”. That excludes mythical tales of the King Arthur sort. Raglan is interested in myths that appear to have been associated with ancient rituals as acted out in dramatic shows (e.g. the Dionysia, May Day rituals, Passion plays) and religious ceremonies. The sorts of myths under examination should be clear from the following words in chapter 13 of The Hero:

The theory that all traditional narratives are myths—that is to say, that they are connected with ritual—may be maintained upon five grounds:

- That there is no other satisfactory way in which they can be explained. . . .

- That these narratives are concerned primarily and chiefly with supernatural beings, kings, and heroes.

- That miracles play a large part in them.

- That the same scenes and incidents appear in many parts of the world.

- That many of these scenes and incidents are explicable in terms of known rituals.

The Hero is close to a century old now so much of Raglan’s discussion is dated, but not all. It is still worth reading, I think, especially where he discusses misconceptions that lead moderns into assuming historicity of many ancient persons and arguments for the link between rituals and myths. It is certainly essential reading for anyone who intends to take up a serious discussion on the relevance of the twenty-two motifs identified as parallels across so many myths.

Common errors in using the 22 points

Often discussions of Raglan’s 22 characteristics of the myth-hero falter for the following reasons:

- Discussions are often about counting points and deciding the historical or non-historical likelihood of a figure according to a number total.

- Raglan makes it clear, however, that the numbers alone do not address something else that is far more important for assessing someone’s historicity.

- Discussions very often fail to account for the real meaning or significance of the 22 characteristics.

- They therefore make assessments based on the letter rather than the spirit of mytho-types.

- Discussions centre around the truncated list form of the 22 points.

- As a consequence the full meaning of some of those points is lost and discussions go awry on misunderstandings.

1. When historical persons are on the list

The emphasis many place upon the number count for assessing historicity no doubt derives from Raglan’s own assessment early in his book: Continue reading “The Rank-Raglan Hero-Type (and Jesus)”

Like this:

Like Loading...