I was dismayed after leaving a religious cult to discover that fallacious thinking that had led me into the cult was not restricted to cult members but was evident throughout society all around me. How I had been so shut off from “the world” not to have noticed how much we shared with “the world”. We always saw ourselves as “called out of this world” and as no longer a part of “this evil world”. We also thought of ourselves as a body, a gathering of converts, unlike any other in the world, so after I had left and reflected on what our operation was “really like” I was dumbstruck to read about how our cult’s M.O. was likewise characteristic of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the Mormons, and others. Okay, so religious cults were bad news for this and that reason, but it was a real blow to my expectations of what I would find “in the world” after I began to observe the same thinking-gone-wrong among not only more benign churches but in society at large.

Then there was that TV documentary on the Hitler Youth. I listened most attentively to interviews with those who had been members before the war and was again struck with clear echoes of the experiences I had come to think, from both personal experience and wider learning, were seductive features of religious cults.

We know the jokes and sayings about the devil’s masterstroke being to convince his dupes that he doesn’t exist. The one sure constant among all cults is that cult members do not believe they belong to a “cult” — it’s all those other weirdos who are the cultists; we are not like them.

And one more thing. Too many of my friends in my old cult turned out to be friends only on condition I remained part of the collective. But there were others whom I saw as true friends, sticking with me even after I was “disfellowshipped” or “cast out into the bond of Satan”. But what a disappointment I felt as I watched so many of them merely gravitate to other cults, most often imitation breakaways from the parent church.

I think in some ways this Vridar blog is a result of those “coming out” experiences. If asked what was the biggest lesson I have taken away from my cult years it would have to be, surely: “I know only too, too well how easy it is for me to be so very wrong.” That’s why readers see so many references to the research, the evidence, the analysis of arguments, of specialists on this blog, and to the examination of common arguments and conclusions, even among other specialists, that we find to be without valid foundation. We try to be careful and get to the facts and analyse the intellectual foundations of what we think and everything is, essentially, provisional. If anything of my experience and subsequent learning can be of some use to anyone else at an appropriate point in their life’s journey I would be satisfied.

I have been saving up scores of online articles published by journalists, political scientists, sociologists, psychologists, historians, about the Trump phenomenon in the United States and only recently I have begun to return to them and read them one by one. There are a number of people in the United States I would consider good friends even though I have never met them face to face. Unfortunately, despite our friendship, I have never had any desire to visit the United States in the same way I like to visit other countries of the world. Perhaps it’s because I see too much of the U.S. here already: on TV and in movies, and especially in the news. Not that all my information has come through today’s mainstream media. I also took up a year’s course in United States history as an undergraduate, and I have followed up much of what I learned at that time by purchasing new books as they relate to special themes of interest from those student years. In our course we covered everything from the invention of the compass through to the confluence of the Kennedy assassination and Beatles Tour, from the Federalist Papers, to the judgments of John Marshall, “Manifest Destiny”, and the Civil Rights Movement. (I recall at one stage taking a special interest in the details of the history of the Rhode Island settlement, possibly at least partly because an American pastor who introduced me to “my cult” was named William Bradford.) Meanwhile, in our English literature courses, I can never remove from my mind novels and plays by William Faulkner, James Baldwin and Tennessee Williams. Then I taught To Kill a Mockingbird in high schools soon afterwards. And I have had a number of American friends, both face to face here in Australia and, of course, online even today. But I cannot presume to know more about what is happening in the United States than what I read and hear. I am always open to correction and learning.

So when I read articles by people-in-the-know comparing Trump supporters to “a cult” I cannot help but pause a moment and wonder.

The following is in no pre-planned order. It is pretty much stream-of-consciousness stuff. Continue reading “Towards Understanding the Trump Movement as a Cult”

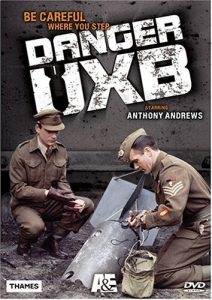

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series

On the other hand, some questions are more pressing. Even not making a decision is still a decision. When I think of life-or-death decisions that demand a choice, I can’t help but recall the series