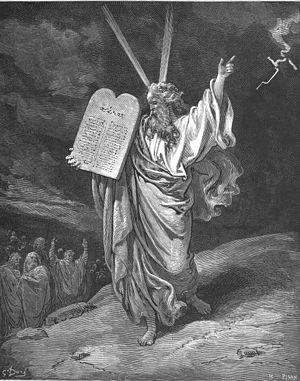

One might encounter the suggestion among biblical scholars that it is highly unlikely that anyone would invent the idea of a saviour figure who is rejected by his own people and is killed at their hands — and especially if that saviour figure is in a Jewish context said to be a Son of David. Well, maybe some Jews who bothered to think about this did contemplate the possibility of a Davidic king one day ruling over all the world with Jerusalem as his capital. But when we read the gospels we quickly understand that there were other Jews who saw the David figure in the light of the other side of the biblical narrative, too — one who went mourning to the mount of Olives with a few faithful followers when being pursued – to the point of death – by his rebel son Absalom. This moment of imminent death was later reputed to have been the subject of a number of Psalms. (Of course, the Davidic figure is only one of a number who is associated with the “Messiah” label. It is most frequently associated with the priests — and it is noteworthy that it is the anointed (messianic) high priest who gives liberty to refugees from unintended capital sins when he dies.)

But even in non-Jewish literature, the concept of a saviour figure being scoffed at and even killed by those he would want to save. It is the central theme of the classic Greek hero, Achilles. The half-divine and half-mortal Achilles pursues what is right and honourable despite knowing that it will result in his own early death.

And the great Hellenistic thinker, Plato, composed a tale that has epitomized the best of Hellenistic values and Western values since. His allegory of the cave tells us how a would-be saviour of a people will do all he can out of compassion to rescue others. But at the same time those he loves and would save will not recognize him or his claims. They will even scoff at him, and even eventually seek to kill him if they ever have the chance.

This is the essence of the Gospel message about the nature, reception and fate of Jesus. Jesus is very much the classic Hellenistic (cum Roman) hero of the gentiles. He is like Achilles and like the saviour in the parable of the Cave.

And he gives hope to all those who would identify with him that they, too, can find heroic meaning in their lives.

The Jews of the later Second Temple Period were influenced by Hellenism (Greek ideas), as we see in the history of the Maccabees. Dying as a martyr was a means to salvation not only for oneself, but — by shedding one’s own blood for God and one’s people, one also became an atonement for them, too.

The Gospel of Jesus is a tale that found a ready welcome among Hellenized pagan and Jew alike. There is nothing mysterious about its invention or reception.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d2afuTvUzBQ]