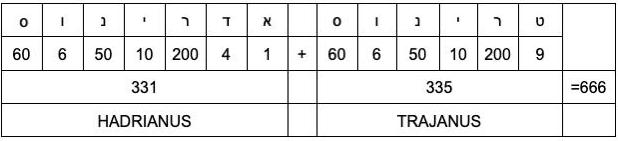

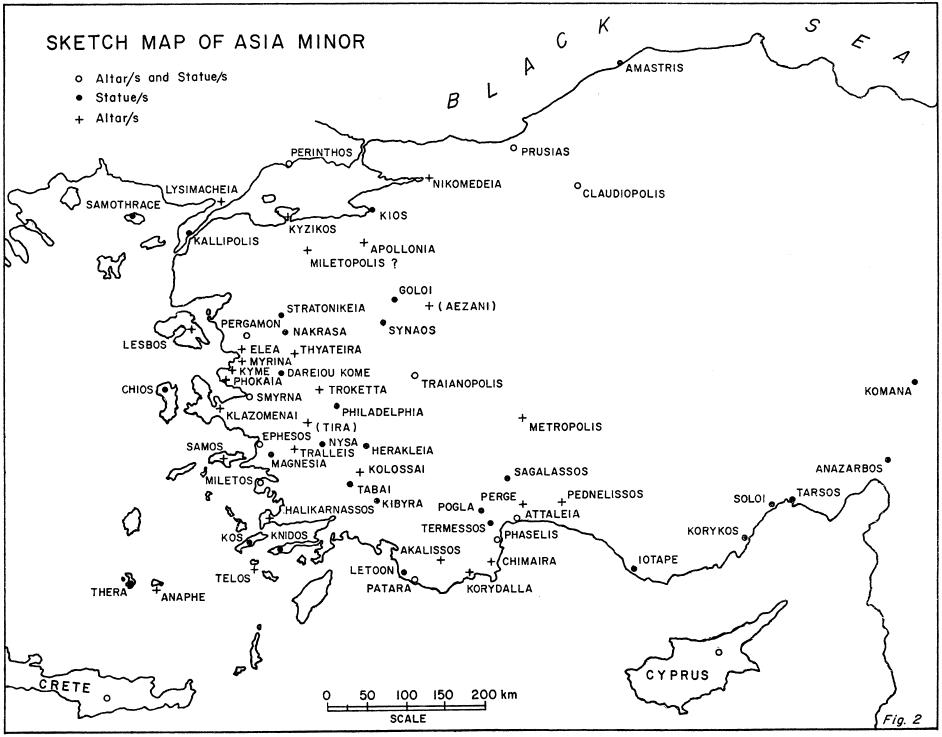

“Does not give the readers any real clue”? Let’s read the [not real] clues:

17: 9 “This calls for a mind with wisdom. The seven heads are seven hills on which the woman sits. 10 They are also seven kings. Five have fallen, one is, the other has not yet come; but when he does come, he must remain for only a little while. 11 The beast who once was, and now is not, is an eighth king. He belongs to the seven and is going to his destruction.

We saw in the previous post that “seven kings” means “seven emperors”. Five “are fallen”. The verb επεσαν (a form of πίπτειν) suggests a violent death. W. cites Lohmeyer,

. . . und επεσαν als „sie starben“ zu fassen, ist sprachlich und sachlich unmöglich. = and to take επεσαν as “they died” is linguistically and factually impossible. (Lohmeyer, 141)

and Aune,

10a οί πέντε έπεσαν, ό εις έστιν, ό άλλος ούπω ήλθεν, “of whom five have fallen, one is living, the other has not yet come.” έπεσαν, “have fallen” (from πίπτειν, “to fall”), does not simply mean “died” but carries the connotation of being overthrown or being killed violently (Lohmeyer, 143; Strobel, ATTS 10 [1963-64] 439). “To fall” is commonly used in the euphemistic metaphorical sense of a person’s violent death, usually in war, in both Israelite-Jewish and Greek literature (Exod 32:28; 1 Sam4:10; 2 Sam 1:19,25,27; 3:38; 21:22; Job 14:10 [LXX only]; 1 Chr 5:10; 20:8; 1 Macc 3:24; 4:15, 34; 2 Macc 12:34; Jdt 7:11; Gk. 1 Enoch 14:6; 1 Cor 10:18; Barn. 12:5; Iliad 8.67, 10.200; 11.157, 500; Xenophon Cyr. 1.4.24; Herodotus 9.67; see Louw-Nida, § 23.105) . . . .

Many of the Roman emperors died violent deaths: Julius Caesar was assassinated by being stabbed twenty-three times (Plutarch Caesar 66.4-14; Suetonius Julius 82; Dio Cassius 44.19.1-5); Caligula was stabbed repeatedly with swords (Suetonius Caligula 58; Tacitus Annals 11.29; Jos. Ant. 19.104—113; Dio Cassius 59.29.4-7; Seneca Dial. 2.18.3; 4.7); Claudius was poisoned (Suetonius Claudius 44-45; Tacitus Annals 12.66-67; 14.63; Pliny Hist. nat. 2.92; 11.189; 22.92); Nero committed suicide (Suetonius Nero 49; Jos. J. W. 4.493); Galba was stabbed to death by many using swords, decapitated, and his corpse mutilated (Tacitus Hist. 1.41.2; Plutarch Galba 27); Otho committed suicide with a dagger (Plutarch Otho 17; Suetonius Otho 11); Vitellius was beaten to death (Suetonius Vit. 17-18; Tacitus Hist. 3.84-85; Jos. J.W. 4.645; Cassius Dio 64.20.1-21.2); and Domitian was assassinated with a dagger (Suetonius Dom 18). (Aune, 949 – my bolded highlighting in all quotations)

W. adds Strobel as another witness:

1. Caligula (-41 AD). Assassinated.

2. Claudius (-54 AD). Poisoned.

3. Nero (-68 AD). Suicide.

4. Vespasian (-79 AD). Died of a fever [Suetonius Vesp. 24.8]. Later, the rumour spread of his poisoning by Titus [Dio Cassius lxvi, 17. . . ].

5 Titus (-81 AD). Died of a fever [Suetonius, Tit. 10]. The suddenness of his death also gave rise to the rumour that he had been violently assassinated [10 Allegedly at the instigation of his brother Domitian. On the matter cf. Paulys R .E . VI, Sp. 2722.].

(Strobel, 439)

So that makes ten, not five, having “fallen”.

But return to where I left off in the last post. We were about to compare Revelation with other apocalyptic literature of the time: 4 Ezra and the Sibylline Oracle V.

The point W. makes is that both of those texts offer the reader numerous clues on how to interpret the metaphorical imagery.

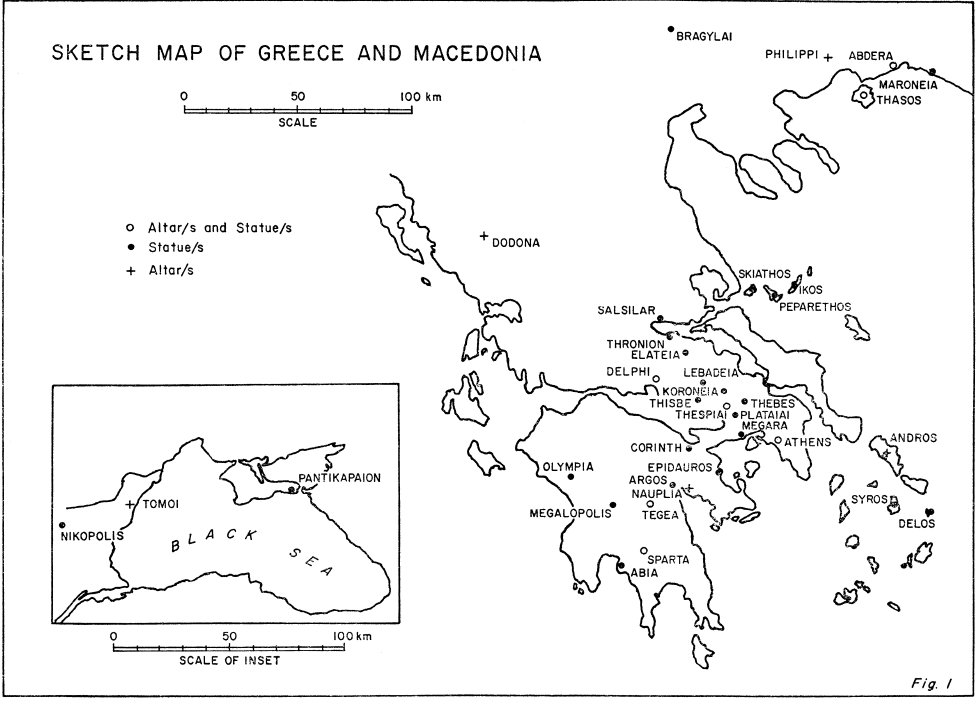

In contrast, the 4Esr 11f surviving eagle vision and its interpretation, for example, offers numerous clues to the identification of the Roman emperors meant in each case. However, for all the literary-critical and redactional-historical problems that this text may raise, it is undisputed among scholars that the second wing, which reigns longer than any of the others, is Augustus, and the three heads are the Flavian emperors Vespasian, Titus and Domitian. This makes it possible to relate a large part of the other wings listed in the vision to Roman emperors or rebellious princes and troop leaders. This unanimity among exegetes, as can be seen in the interpretation of the eagle vision 4Esr 11f is lacking in view of the interpretation of Apk 17:10f, precisely because in these verses the apocalypticist offers no clear indications of the historical classification of the seven or eight βασιλείς.

(Witulski, 327)

The same assessment is made in relation to the Sibylline Oracle V,

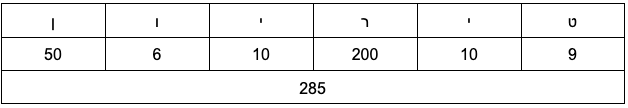

Even within the discussion of the individual Roman emperors from Julius Caesar to Hadrian’s adopted sons in Sib V 12-51, there are sufficiently clear references in each case to allow readers to clearly identify the individual emperors.

Compare 4 Ezra 11. Although the identifications of many of the details are open to dispute, there is enough description provided for readers to have little doubt about the identity of Augustus being the second ruler after Julius Caesar (the second wing who reigned for a very long time) and again, enough details are offered to enable readers to identify Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian (three heads, after the death of the first, one of the remaining two “devoured” the other — as Domitian was rumoured to have killed Titus),

11:1 On the second night I had a dream, and, behold, there came up from the sea an eagle, which had twelve feathered wings, and three heads.

11:2 And I saw, and, behold, she spread her wings over all the earth . . .1:12 And I looked, and, behold, on the right side there arose one feather, and reigned over all the earth;

11:13 And so it was, that when it reigned, the end of it came, and the place thereof appeared no more: so the next wing following stood up, and reigned, and had a long reign . . . [Augustus ruled longer than any other emperor]11:29 And when they were planning, behold, there awakened one of the heads that were at rest, namely, the one that was in the middle; for that was greater than the other two heads.

11:30 And I saw how it allied the two heads with itself . . . .11:32 Moreover this middle head gained control of the whole earth [Vespasian], and with much oppression dominated its inhabitants; and it had greater power over the world than all the wings that had gone before.

11:33 And after this I looked, and behold, the middle head suddenly disappeared and was no more, just as the wings had done.

11:34 But there remained the two heads, which also ruled over the earth and its inhabitants.

11:35 And I looked, and behold, the head upon the right side devoured the one that was upon the left side. [Domitian thought to have assassinated Titus]

Similarly with the Sibylline Oracle V, 10-50:

. . . after the man of the race and blood of Assaracus, who came from Troy, and broke through the raging fire, and after many kings and warlike men, and after the babes whom the wolf took for her nurslings, shall come a king first of all, the first letter of whose name shall sum twice ten [twice ten = K, Caesar]; he shall prevail greatly in war : and for his first sign he shall have the number ten [ten = I, i.e. I/Julius];

so that after him shall rule one who has the first letter as his initial [first letter =A, i.e. Augustus]; before whom Thrace shall cower [battle at Philippi, 42 B.C.] and Sicily [defeat of Pompey’s son who had controlled Sicily with his fleet], then Memphis, Memphis brought low by the fault of her leaders, and of a woman undaunted [i.e. Cleopatra], who fell on the wave (by the spear ?). He shall give laws to the peoples and bring all into subjection, and after a long time shall hand on his kingship to one who shall have the number three hundred for his first letter [300 = T, Tiberius], and a name well known from a river [= Tiber River], whose sway shall reach to the Persians and Babylon : and he shall smite the Medes with the spear.

Then shall rule one whose name-letter is the number three [3 = G, Gaius] ; then one whose initial is twenty [20 = K, i.e. Claudius]: he shall reach the furthest ebb of Ocean’s tide [i.e. Britain], swiftly travelling with his Ausonian company. Then one with the letter fifty shall be king [50 = N, i.e. Nero], a fell dragon breathing out grievous war [i.e. war against the Jews from 66 CE], who shall lift his hand against his own people to slay them, and shall spread confusion, playing the athlete, charioteer, assassin, a man of many ill-deeds [Nero participated in chariot races, assassinated his mother and others]; he shall cut through the mountain between two seas and stain it with blood [isthmus canal of Corinth, 6000 Jewish slaves sent to work on it]; yet he shall vanish to destruction (?) ; then he shall return, making himself equal to God : but God shall reveal his nothingness.

Three kings after him shall perish at each other’s hand [civil war and successive emperors Galba, Otho, Vitellius]; then shall come a great destroyer of the godly, whom the number seventy plainly shows [70 = O, Vespasian, in Greek, Ούεσπασιανός]. His son, revealed by the number three hundred [300 = T, Titus], shall take away his power [Rumour was that Titus poisoned his father]. After him shall rule a devouring tyrant, marked by the letter four [4 = D, Domitian], and then a venerable man, by number fifty [50 = N, the aged Nerva who reduced harsh penalties on Jews] :

but after him one to whom falls the initial sign three hundred, a Celt, ranging the mountains [300 = T, Trajan, from Spain, conquered mountainous Armenia], but hastening to the clash of conflict he shall not escape an unseemly doom, but shall fall ; the dust of a strange land shall cover him in death, a land named from the Nemean flower. Following him a silver-haired king shall reign : his name is that of a sea [Hadrian, cf Adriatic Sea]; he shall be a man of excellence and all discernment. . . . [written before the Bar Kochba war at a time when it was hoped he would restore the temple?]

Contrast the seven kings in Revelation 17. Readers are left guessing without sufficient clues to identify any of them with certainty. Here is Strobel’s summary of the problem (translated from the German):

If we begin the ‘five’ with Augustus and ignore the interregnum emperors, the ‘one’ is Vespasian (69-79) and the ‘other’, who may only remain for a ‘short time’, is Titus (79-81). If we count from Caesar onwards, Nero would be the ‘one’, currently reigning emperor (54-68) and Vespasian the ‘other’, who nevertheless held the throne for 11 years. If we include the interregnum emperors (beginning with Augustus), a writing under Galba in particular suggests itself as the ‘One’ who is. He still ruled from Jun 68 to January 69 and also found some recognition in the Orient. . . . In addition, one also remembers those early church testimonies which claim to know of a death of the apocalypticist under Nero or of a death of the Zebedaid John in the years before the destruction of Jerusalem. Insofar as the undoubtedly important old Christian tradition of a writing under Domitian is considered relevant, one considers the processing of a source originating from the time of Vespasian . . . (433f)

A remarkable solution, despite its idiosyncrasy, is offered by E. B. Allo among the modern interpreters. Beginning the count with Nero without sufficient reasons and including at least two of the three intermediate emperors, he succeeds in proving Domitian to be the ‘one’. . . . (436)

But why not begin the count with Tiberius? The rationale for this starting point is that it marks the crucifixion of Jesus and hence the “real” turning point of history:

His imagined point in world history is neither the beginnings of the Principate nor the rebirth of Rome in the golden, Augustan age, of which Virgil, for example, sings. Rather, it is unquestionably identical with the term of the cross and the exaltation of Christ as ‘Lord of lords’ under Tiberius. In other words: for the apocalypticist, the cross and the exaltation signify the telos of the old aeon in an eminently historical sense . . . . (437)

But no, there is even a reason to exclude Tiberius and begin with Gaius Caligula:

. . . the Roman emperors after Tiberius are typical representatives of the final anti-Christian phase of world history. Tiberius, whose reign began long before the appearance of Christ (= 14 A.D.), was naturally not included in the series of ‘anti-Christian’ emperors who had risen since the Messiah. The exclusively post-teleological aspect necessarily led to the restriction to those emperors who came to power only after Christ. They were introduced by Caligula. . . . since the apocalypticist undoubtedly had in mind only the Roman emperors of the post-Messianic period. (440)

No doubt there are other starting points, omissions and inclusions, that can only add to the confusion or at least to the uncertainty of any proposal that attempts to align the heads with a sequence of historical emperors.

So why is the author of Revelation so opaque? So indecipherable in relation to the history of the Roman emperors?

Continuing…..

Aune, David E. Revelation 17-22. Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 52C. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Inc, 1998.

Bate, Herbert N., trans. The Sibylline Oracles, Books III-V. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1918. http://archive.org/details/sibyllineoracles00bateiala.

Lohmeyer, E. Die Offenbarung des Johannes. Tübingen, J.C.B. Mohr (P. Siebeck), 1926. http://archive.org/details/dieoffenbarungde0000unse_n5x5.

Strobel, A. “Abfassung Und Geschichts Theologie Der Apokalypse Nach Kap. XVII. 9–12.” New Testament Studies 10, no. 4 (July 1964): 433–45. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688500001880.

Witulski, Thomas. Die Johannesoffenbarung Und Kaiser Hadrian: Studien Zur Datierung Der Neutestamentlichen Apokalypse. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007.