. . . . then go to Peter Kirby’s blog where has a list of Blogs Abuzz for Jesus’ Wife.

I saw the Harvard Theological Review article was out around midnight last night so decided to shut down my computer and get some sleep.

Sorry, not interested.

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

. . . . then go to Peter Kirby’s blog where has a list of Blogs Abuzz for Jesus’ Wife.

I saw the Harvard Theological Review article was out around midnight last night so decided to shut down my computer and get some sleep.

Sorry, not interested.

The Holy Great One will come forth from His dwelling,

And the eternal God will tread upon the earth, (even) on Mount Sinai,

[And appear from His camp]

And appear in the strength of His might from the heaven of heavens.And all shall be smitten with fear

And the Watchers shall quake,

And great fear and trembling shall seize them unto the ends of the earth.And the high mountains shall be shaken,

And the high hills shall be made low,

And shall melt like wax before the flameAnd the earth shall be wholly rent in sunder,

And all that is upon the earth shall perish,

And there shall be a judgement upon all (men).

Immediately after the tribulation of those days shall the sun be darkened, and the moon shall not give her light, and the stars shall fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens shall be shaken

And I beheld when he had opened the sixth seal, and, lo, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became as blood;

And the stars of heaven fell unto the earth, even as a fig tree casteth her untimely figs, when she is shaken of a mighty wind.

And the heaven departed as a scroll when it is rolled together; and every mountain and island were moved out of their places.

And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains;

And said to the mountains and rocks, Fall on us, and hide us from the face of him that sitteth on the throne, and from the wrath of the Lamb:

For the great day of his wrath is come; and who shall be able to stand?

What does all this mean? Such apocalyptic had a long heritage, as passages from Enoch (above) and Micah, Jeremiah and Isaiah (below) testify. How did the authors expect readers/hearers to interpret such language?

Again from Richard Horsley, this time from Scribes, Visionaries and the Politics of Second Temple Judea . . .

.

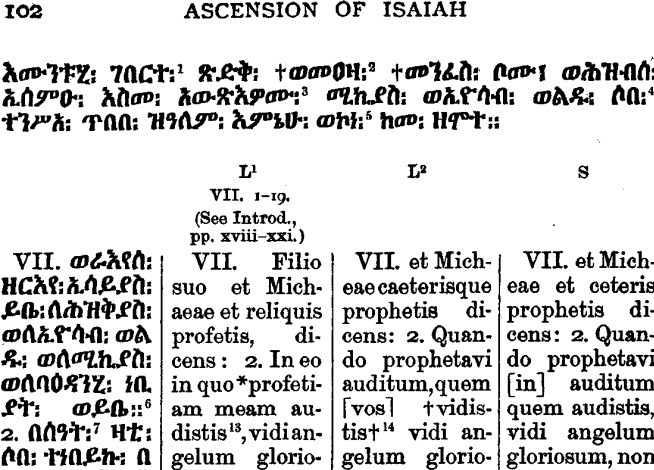

| In the previous post of the series I proposed that the Vision of Isaiah was the source of Simon/Paul’s gospel.

This post will look at the place in the Vision that contains the major difference between the two branches of its textual tradition. Obviously, at least one of the readings is not authentic. But, as I will show, there are good reasons to think that neither reading was part of the original.

|

.

The passages in question are located in chapter 11 of the Vision. In the L2 and S versions the Lord’s mission in the world is presented by a single sentence:

2… And I saw one like a son of man, and he dwelt with men in the world, and they did not recognize him.

In place of this the Ethiopic versions have 21 verses, 17 of which are devoted to a miraculous birth story:

2 And I saw a woman of the family of David the prophet whose name (was) Mary, and she (was) a virgin and was betrothed to a man whose name (was) Joseph, a carpenter, and he also (was) of the seed and family of the righteous David of Bethlehem in Judah. 3 And he came into his lot. And when she was betrothed, she was found to be pregnant, and Joseph the carpenter wished to divorce her. 4 But the angel of the Spirit appeared in this world, and after this Joseph did not divorce Mary; but he did not reveal this matter to anyone. 5 And he did not approach Mary, but kept her as a holy virgin, although she was pregnant. 6 And he did not live with her for two months.

7 And after two months of days, while Joseph was in his house, and Mary his wife, but both alone, 8 it came about, when they were alone, that Mary then looked with her eyes and saw a small infant, and she was astounded. 9 And after her astonishment had worn off, her womb was found as (it was) at first, before she had conceived. 10 And when her husband, Joseph, said to her, “What has made you astounded?” his eyes were opened, and he saw the infant and praised the Lord, because the Lord had come in his lot.

11 And a voice came to them, “Do not tell this vision to anyone.” 12 But the story about the infant was spread abroad in Bethlehem.

13 Some said, “The virgin Mary has given birth before she has been married two months.” 14 But many said, “She did not give birth; the midwife did not go up (to her), and we did not hear (any) cries of pain.” And they were all blinded concerning him; they all knew about him, but they did not know from where he was.

15 And they took him and went to Nazareth in Galilee. 16 And I saw, O Hezekiah and Josab my son, and say to the other prophets also who are standing by, that it was hidden from all the heavens and all the princes and every god of this world. 17 And I saw (that) in Nazareth he sucked the breast like an infant, as was customary, that he might not be recognized.

18 And when he had grown up, he performed great signs and miracles in the land of Israel and (in) Jerusalem.

19 And after this the adversary envied him and roused the children of Israel, who did not know who he was, against him. And they handed him to the ruler, and crucified him, and he descended to the angel who (is) in Sheol. 20 In Jerusalem, indeed, I saw how they crucified him on a tree, 21 and likewise (how) after the third day he and remained (many) days. 22 And the angel who led me said to me, “Understand, Isaiah.” And I saw when he sent out the twelve disciples and ascended.

(M. A. Knibb, “Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, pp. 174-75.)

One Substitution or Two?

Most scholars think the L2 and S version of the Lord’s earthly mission is far too brief to be original. The foreshadowing in the Vision “expects some emphasis on the Beloved assuming human form as well as some story of crucifixion” (p. 483, n. 56). But instead L2 and S give us what looks like some kind of Johannine-inspired one-line summary: “he dwelt with men in the world” (cf. Jn. 1:14). Those who think the Ethiopic reading represents the original see the L2 and S verse as a terse substitution inserted by someone who considered the original to be insufficiently orthodox.

But from the recognition that 11:2 of the L2/S branch is a sanitized substitute, it does not necessarily follow that 11:2-22 in the Ethiopic versions is authentic. That passage too is rejected by some (e.g., R. Laurence, F.C. Burkitt). And although most are inclined to accept it as original, they base that inclination on the primitive character of its birth narrative. Thus, for example, Knibb says “the primitive character of the narrative of the birth of Jesus suggests very strongly that the Eth[iopic version] has preserved the original form of the text” (“Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, p. 150)

It is true that the Vision’s birth narrative, when compared to those in GMatthew and GLuke, looks primitive. But there are good grounds for thinking that the original Vision did not have a birth narrative at all. A later substitution is still a later substitution even if it is a birth narrative that is inserted and its character is primitive compared to subsequent nativity stories. Robert G. Hall sensed this and in a footnote wrote:

Could the virgin birth story have been added after the composition of the Ascension of Isaiah? Even if we conclude that this virgin birth story was added later, the pattern of repetition in the Vision probably implies that the omission of 11:1-22 in L2 and Slav is secondary. The foreshadowing expects some emphasis on the Beloved assuming human form as well as some story of crucifixion. Could the story original to the text have offended both the scribe behind L2 Slav and the scribe behind the rest of the witnesses? The scribe behind the Ethiopic would then have inserted the virgin birth story and the scribe behind L2 Slav would have omitted the whole account. The virgin birth story is, however, very old and perhaps it is best not to speculate. (“Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, n. 56, p. 483, my bolding)

I agree that both the E and L2/S readings at 11:2 could be replacement passages, but I think Hall’s advice not to speculate should be disregarded, for it is his very observations about the Vision that provide some good reasons to suspect that 11:2-22 did not belong to the original text. It is he who points out that foreshadowing and repetition characterize the Vision—except when it comes to the birth story! Continue reading “A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 8: The Source of Simon/Paul’s Gospel (continued)”

The Messiah figure (or Christ) in the Book of Enoch, specifically in the Parables or Similitudes section of that book, has several attributes and performs certain functions that make him a precursor of the Christ figure who became the focus of Christianity.

Paul’s understanding of who and what Christ was appears to have been influenced by the Book of Parables in 1 Enoch. Paul says that his gospel was revealed to him so it is easy to assume that either God revealed Christ to him in a vision or that he developed his own Christ concept to preach. However, the similarities of his Christ with the Christ/Messiah in Enoch are striking. Moreover, the same Enochic literature teaches that Christ is a figure unknown except to those to whom he is revealed from heaven. Or was he revealed to Paul, at least in part, through the Book of Enoch?

This account of at least one Jewish group’s beliefs about the Messiah before the time of Paul (and Jesus) is taken from The Messiah: A Comparative Study of the Enochic Son of Man and the Pauline Kyrios by James A. Waddell. The previous post in this series is here.

First things first. Let’s establish where in the Parables of Enoch (or Book of Parables, BP) we read the actual term “Messiah” or “Christ” — meaning “Anointed One”. The word occurs twice:

And on the day of their affliction there shall be rest on the earth,

And before them they shall fall and not rise again:And there shall be no one to take them with his hands and raise them:

For they have denied the Lord of Spirits and His Anointed.

The name of the Lord of Spirits be blessed.

And he said unto me: ‘All these things which thou hast seen shall serve the dominion of His Anointed that he may be potent and mighty on the earth.’

We shall see through this series that this Christ, the Anointed One, is also named the Righteous One, the Chosen One, the Son of Man, and Name of the Lord of Spirits. We begin to look at some of the attributes or nature of this being in this post, and then we will (courtesy of Waddell) study the functions, the role, of this Messiah.

The Messiah in the Book of Enoch is a human being. It is the man Enoch himself who is (near the end of the book) declared to the Messiah himself. Enoch is the sixth human generation after Adam, or the seventh, counting inclusively. The human nature of Enoch is driven home in the following:

1 Enoch 37:1

The second vision which he saw, the vision of wisdom — which Enoch the son of Jared, the son of Mahalalel, the son of Cainan, the son of Enos, the son of Seth, the son of Adam, saw.

Compare 60:8 (Noah speaking)

the garden where the elect and righteous dwell, where my grandfather was taken up, the seventh from Adam, the first man whom the Lord of Spirits created.

So Enoch, we are emphatically assured, belongs to the human race. He is a descendant of Adam.

Then at the end of the BP this same human Enoch is explicitly identified with the Son of Man: Continue reading “Christ Before Christianity, 2: A Man Ascended to Heaven”

The Christ we read about in the letters of the Apostle Paul has many striking similarities to another Christ we read about in the earlier Second Temple Jewish Book of the Parables of Enoch. So much so that James A. Waddell, Philip Markowicz Visiting Professor of Jewish Biblical Studies at the University of Toledo, argues in The Messiah: A Comparative Study of the Enochic Son of Man and the Pauline Kyrios that Paul belonged to that stream of Jewish intellectual tradition that developed its concept of Christ, the Messiah, out of the messiah traditions we read about in the Book of Enoch.

(The Book of Parables is also known as the Similitudes of Enoch. In this post I will follow Waddell and use BP to refer to this text.)

Too late?

Some readers will immediately ask if the Enochic Book of Parables is too late. Is it not from a post-Gospel era? Waddell informs those of us who still think this that we are out of date:

Only recently has specific research on the date of BP created a shift in the scholarly consensus among specialists of the Enoch literature. This consensus established the messiah traditions of BP, if not the text itself, to a date prior to Paul. (p. 22 of The Messiah)

Waddell’s book was published in 2010 and his claim about the scholarly consensus is supported by reference to half a dozen articles in Boccaccini’s Enoch and the Messiah Son of Man (2008) among a list of earlier publications.

To me, and I am sure to many others, questions of dating are important. So this post attempts primarily to explain Waddell’s rationale (presumably shared by many of his peers) for dating the BP to a pre-Christian era. The next post will begin to examine the nature of the Christ/Messiah as understood before Paul among the Jews associated with this document.

|

Maurice Casey’s ‘Son of Man’ arguments Other readers may wonder about the stress upon the “Son of Man” in both the above titles given that (1) Paul never uses the “Son of Man” in relation to Christ, and (2) Emeritus Professor Maurice Casey is reputed to have written “the definitive” work on the Son of Man and supposedly buries any notion that “son of man” was employed as a messianic title up to and including the time of Jesus. As for (1), Waddell’s thesis includes a cogent theological explanation why Paul would have shunned the term in relation to his Christ; as for (2), Waddell exposes inconsistencies in Casey’s treatment of the evidence and generally leaves Casey’s approach to the question looking tendentious indeed. |

|

Larry Hurtado’s ‘worship’ arguments Another contemporary Emeritus Professor addressed by Waddell is Larry Hurtado. Waddell agrees with Hurtado’s case that the evidence argues that the Christ Jesus was worshiped “from the moment of the Easter experience” (jargon designed to harmonize the Gospel-Acts narrative with modern rationalist sensibilities) for the beginning of Christianity, but rejects Hurtado’s complementary claim that the worship of any other figure apart from God himself was unknown among Jews before Christianity. Waddell argues that evidence contradicting a scholar’s personal faith has been treated tendentiously. The BP do indeed depict early Jewish worship of a being alongside God. |

.

Continue reading “Christ Before Christianity, 1: Dating the Parables of Enoch“

Continuing from the previous post: The Carrier-Goodacre Exchange (Part 1) on the Historicity of Jesus.

I have typed out the gist of the arguments for and against the historicity of Jesus as argued by Richard Carrier (RC) and Mark Goodacre (MG) on Unbelievable, a program hosted by Justin Brierley (JB) on Premier Christian Radio. My own comments are in side boxes.

——————————————

JB: The main sticking point so far — for MG, the references in Paul cannot be attributed to him believing in an entirely celestial being in a heavenly realm. So many (even throw-away) references in Paul seem to reference historical people who knew Jesus. But RC is adamant that all these references can be seen through the mythicist lens as references to a purely spiritual, heavenly Jesus.

RC: Yes. Paul, for example, never says Peter met Jesus. Peter came first. That was the problem. The other apostles had prior authority to Paul.

Peter was thus the first, but the first what? He was the first to receive a revelation. 1 Corinthians 15 thus says Jesus according to the scriptures* died and rose again and he was THEN seen by Peter and the others. There is no reference to them seeing him before he died. No reference to them being with him, chosen by him, etc. (The issue of Peter seeing and knowing Jesus personally never surfaces in their debates.)

MG: But Paul is talking about resurrection there, so of course he’s not talking about other things. “But what we have to do as historians is to look at what people give away in passing. And what he gives away in passing there is his knowledge of an early Christian movement focused on someone who died.” And then there are the other characters who appear elsewhere in Paul’s epistles whom Paul has personal conversations with in Jerusalem.

RC: Yes, these are the first apostles. These are the first to receive the revelations of the Jesus according to the myth theory.

There is no clear case where Paul gives the answer either way – – –

——————————————

JB: If I was reading Paul without ever having read the Gospels, would I come away thinking Paul was talking of a heavenly Jesus? It strikes JB that there was enough to make one think there was something that happened in real life. Continue reading “Carrier-Goodacre (part 2) on the Historicity of Jesus”

One common argument of Christian apologists — both lay and scholarly — in favour of the Gospel accounts being based on “authentic” historical traditions and written by authors motivated by, or limited to, telling “the truth” as they understood it, is that the miracles of Jesus are told “plainly”, “matter-of-factly”, without any garish flourish. Miracles of Jesus in the much later “apocryphal gospels”, on the other hand, are rightly said to be told quite differently and with much embellishment that serves to impress readers with the wonder and awesomeness of Jesus’ power.

The difference, we are often told, is testimony to the historical basis of the Gospel record.

I used to respond to this challenge with a dot-point list of miracle types. What? Are you really suggesting that walking on water or stilling a storm or rising from the dead are not “fanciful” acts?

But I was trying to kid myself to some extent. Of course they are fanciful, but being fanciful in that sense is the very definition of a miracle, however it is told.

The point the apologist makes is not that miracles are indeed miraculous, but that the Bible relates them most simply and matter-of-factly quite unlike the presentations of miracles we read in the apocryphal gospels.

Read the Infancy Gospel of Thomas and one quickly comes face to face with an infant from a horror movie. A child strikes mockers dead on the spot for mocking. His art-work steps out into reality and disbelievers are struck dead or blinded with no thought of asking questions later.

And the Gospel of Peter knows how to narrate a resurrection. None of this “Joseph sealed the tomb and they all went off to keep the sabbath and by the time Sunday-morning came around . . . .”. Nope. Let’s have Jesus emerge from the tomb with guards being awakened and rushing to call their commander to witness the spectacle, and great angels descending and re-ascending with their charge fastened between them and his head exalted through the clouds, all accompanied by a great voice from heaven and responses from below . . . . Now that’s a resurrection scene!

There is a difference in tone between the miracles of Jesus in the canonical gospels and those found in their apocryphal counterparts.

The apologist — even the scholarly one as I mentioned above — jumps on this difference as evidence that the “plain and simple” narration of the gospels is evidence of intent to convey downright facts.

Unfortunately, this conclusion is evidence of nothing more profound than the propensity of the faithful to fall into the fallacy of “the false dichotomy“. Continue reading “Why were Jesus’ miracles told “plainly” in the Bible but “fancifully” in the Apocryphal Gospels?”

Reading ancient texts quite often brings little eyebrow-raising surprises and curiosities — like this passage from Philo’s On the Life of Moses, II. He explains that the unique beauty of the sabbath resulted from it having “no female” element in it whatsoever:

XXXIX. (209) Moreover, in accordance with the honour due to the Creator of the universe, the prophet hallowed the sacred seventh day, beholding with eyes of more acute sight than those of mortals its pre-eminent beauty, which had already been deeply impressed on the heaven and the whole universal world, and had been borne about as an image by nature itself in her own bosom;

(210) for first of all Moses found that day destitute of any mother, and devoid of all participation in the female generation, being born of the Father alone without any propagation by means of seed, and being born without any conception on the part of any mother. And then he beheld not only this, that it was very beautiful and destitute of any mother, neither being born of corruption nor liable to corruption; . . . .

So one born of a mother is inferior because it is produced by means of “seed”?

It’s enough to make one wonder why the Christians didn’t concoct a myth of Jesus springing forth from the Father himself. Come to think of it, some Christians did believe this. Moreover, I supposed the virgin birth was beautiful because it was not the semen of a pagan god that initiated the process, but the Spirit of God himself. So even the virgin birth is entirely in keeping with this Platonic philosophy.

When Bart Ehrman tries to have us believe that the Christian nativity scene is without any counterpart in the world of pagan myths because there is no “seed” from a god involved in the process, he is surely falling behind the times. By the time of Christianity the learned ones had discovered, with the help of Platonic philosophy, a far higher and purer state of being and generation than was ever possible with anthropomorphic deities. But it’s still the same story, the same motif. Only moved up to a “higher” philosophical plane.

In my previous post that began to address Dr McGrath’s “review” of a small section of Earl Doherty’s 10th chapter. I focussed on Dr McGrath’s opening assertion that the Ascension of Isaiah in its Christian version dates from the latter half of the second century and criticizing Doherty for failing to address this “conclusion” or justify his own disagreement with it:

The Christian version is dated by scholars to the second half of the second century at the earliest, and Doherty does not even address that conclusion or show awareness of it, much less present anything that might justify disagreeing with it.

It’s pretty hard to show any awareness of a date that is fabricated entirely in Dr McGrath’s imagination.

McGrath’s claim about the dating of the Christian version by scholars is misleading. I quoted a raft of experts and commentators on the Asc. Isa. in my previous post, mostly from sources Dr McGrath himself linked, demonstrating that they all place the various Christian parts of the Asc. Isa. much earlier and it is only the final compilation of these that was accomplished in the later second century. McGrath’s date for the assembling of the parts is irrelevant to a discussion that is about the thought-world of parts that most scholars are agreed dates between the late first and early second centuries.

I asked McGrath through a mediator (since McGrath says he won’t address me) for the source for his assertion that the Asc. Isa. should be dated to the late second century. Dr McGrath is not a fool and he knew he had overstated or mis-stated his case (perhaps as a result of my previous response to his “review”?) so he opted to answer another question: to cite an article in which scholars date the Christian portions of the Asc. Isa. to the second century (not late in that century). Dr McGrath has explained that his source was an article, from 1990, by Robert G. Hall. In that article Hall concludes that the Asc. Isa. dates from the end of the first century or beginning of the second, thus flatly contradicting Dr McGrath’s initial claim in his “review” of Doherty’s argument for a late second century date. This is surely a tacit admission that Doherty’s date for the Asc. Isa. is consistent after all with scholarly views:

We have also suggested that the Ascension of Isaiah belongs among writings which reflect prophetic conflict and which date from the end of the first century or the beginning of the second. (Hall, Robert G.. (1990). The Ascension of Isaiah: Community Situation, Date, and Place in Early Christianity. Journal of Biblical Literature. 109 (2), p.306. — my emphasis)

Here is another paragraph from the same article explaining other scholar’s views of the date of the Asc. Isa.: Continue reading “Dr McGrath: Doherty was right after all about the date for the Ascension of Isaiah”

Earlier this month I posted notes from the Acts of Mark that René Salm had shared.

Since then René Salm has posted the first ever English translation of the Acts of Mark on his website. Translator is Dr Mark A. House.

See The Acts of Mark: Translation.

This is “a fairly literal translation, and so it may sound a bit rough – it is a provisional translation.

René has another page of notes discussion the background to his own interest in the Acts and comments on the translation itself.

See The Acts of Mark: Notes and Bibliography

Of particular interest is René’s discussion of the date of the text. What relevance could an ostensibly 5th century text have for mythicists or anyone interested in the origins of Christianity?

See The Acts of Mark: “What is the date of this text?”

There’s main gateway to these links is Rene’s resources for the study of Christian origins page which also leads to a summary of the Acts.

The same page contains a translation of part of a work by Ditlef Nielsen’s (1904 ) titled The Natsarene and Hidden Gnosis.

René Salm has kindly shared with me a new translation (I think it’s the first English translation) of the Acts of Mark, a text I had never heard of till now. Until René’s contribution the most detail available on the internet about this document was from an old Synoptic L exchange between Philip James McCosker and Mark Goodacre. McCosker posted the abstract of a 1992 thesis about the Acts, which I copy here. Of particular interest, I also copy here notes from René in which he epitomizes much of the content.

Here is an abstract from a dissertation written recently here at Harvard

on the Acts of Mark, I hope it helps. . . . .There are also other items of literature listed below.

A.D.Callahan ‘The Acts of Saint Mark : an introduction and commentary’

Thesis (Ph.D.)–Harvard University, 1992

According to the Church’s most venerable traditions, it was the

evangelist reputed to have written the Second Gospel who was first to

proclaim the Christian message in the Nile Valley; Mark the Evangelist

was Alexandria’s first bishop and first martyr, his miracles, prodigies

and passion recorded in the so-called Acts of Saint Mark (AM). The AM

probably existed in some literary form by the late fourth century. The

age of the underlying traditions, of course, remains an open question.

Such a dating puts the AM in the same historical continuum as other of

the so-called apocryphal Acts, yet it is little known and virtually

ignored by modern Western scholarship. Continue reading “The Acts of Mark”

The Gospel of Marcion, continues Paul Louis Couchoud, was fascinating reading but received outside Marcionite churches only after appropriate corrections. The first of these was in Alexandria by the gnostic philosopher Basilides.

The Gospel of Marcion, continues Paul Louis Couchoud, was fascinating reading but received outside Marcionite churches only after appropriate corrections. The first of these was in Alexandria by the gnostic philosopher Basilides.

The works of Basilides have been lost. We know they consisted of 24 books making up his Gospel and Commentaries. From Hegemonius we know the gospel of Basilides included Marcion’s parable of Dives [the Rich Man] and Lazarus. In Marcion’s gospel this parable addressed the Jews exclusively. The place of torment and place of refreshment (for those who obey the Law and Prophets) were both in “Hell”. Heaven is the bosom reserved only for those who belong to the Good God (who is greater than the Jewish creator god).

Basilides’ gospel did not have Jesus actually crucified. For Basilides, who may have been influenced by Buddhism, all suffering is the consequence of sin, even if for sins committed in a former life.

Basilides taught that Jesus somehow was confused with Simon of Cyrene and it was this Simon who was crucified in his place. Jesus, being supernaturally related to God or Mind was able to change his appearance at will, and so escaped crucifixion and was taken, laughing at how he had deceived mere mortals, to heaven. Thus the Pauline theme of the mocked Archontes/Rulers was maintained, but in the process the crucifixion was denied — a denial we see repeated in the Acts of John and in the Koran of Islam.

So Basilides was extending the original notion found in Marcin’s gospel that Jesus had no real human body.

Basilides is apparently responsible for the institution of the festival of the Epiphany of Jesus and of his Baptism on January 6.

This makes us think that according to Basilides the manifestation of Jesus as a god took place at a baptism similar to the water festival celebrated at Alexandria on January 6, but in honour of Osiris. (ppp. 169-170)

Next post, the Roman reaction: the Gospel of Mark

This post follows on from my earlier post on The Secret Book of John, possibly a Jewish pre-Christian work, as translated and annotated by Stevan Davies.

Stevan Davies’ translation of the Secret Book/Apocryphon of John is available online at The Gnostic Society Library.

The Prologue is said to be a Christian addition to an earlier non-Christian book. But what sort of Christianity interested the scribe who added this? The disciple John is said to see Jesus appearing variably as a child, an old man and a young man. I am reminded of Irenaeus’s belief that Jesus had to have been past his 50th birthday when he was crucified so he could experience all the life stages of humanity and thus be the saviour of all. One is also reminded of the letter of 1 John that addresses the “children, fathers and young men” in the church. Of related interest to me are some of the earliest Christian art forms that depict Jesus as a little child – in particular when he faces an elderly John the Baptist to be baptized. Christ crucified does not appear.

The same prologue has Jesus say “I am the Father, the Mother, the Son. I am the incorruptible Purity.” The Holy Spirit in the eastern churches was grammatically feminine and so the Holy Spirit itself came to be regarded as feminine.

The same prologue has Jesus say “I am the Father, the Mother, the Son. I am the incorruptible Purity.” The Holy Spirit in the eastern churches was grammatically feminine and so the Holy Spirit itself came to be regarded as feminine.

The Christianity that is appropriating this originally non-Christian gnostic text was one that viewed Christ as not only a discrete personality who had been crucified and risen as a saviour, but one that also accommodated gnostic-like ideas of Christ being identified in the different forms of humanity. Or perhaps it is more correct to say that the range of humanity is a representation of the divine.

But enough of my ramblings and speculative asides. Back to the gnostic myth. Continue reading “The Gnostic Gospel (Apocryphon) of John – 2”

In his review of Maurice Goguel‘s attack on Jesus mythicism Earl Doherty writes (with my emphasis):

In his review of Maurice Goguel‘s attack on Jesus mythicism Earl Doherty writes (with my emphasis):

It was at the opening of the 20th century that the first serious presentations of the Jesus Myth theory appeared. The earliest efforts by such as Robertson, Drews, Jensen and Smith were, from a modern point of view, less than perfect, lacking a comprehensive explanation for all aspects of the issue. Pre-Christian cults, astral religions, obscure parallels with foreign cultures, even the epic of Gilgamesh, went into a somewhat hodge-podge mix; many of them didn’t seem to know quite what to do with Paul. It wasn’t until the 1920s that Paul-Louis Couchoud in France offered a more coherent scenario, identifying Christ in the eyes of Paul as a spiritual being. (While not relying upon him, I would trace my type of thinking back to Couchoud, rather than the more recent G. A. Wells who, in my opinion, misread Paul’s understanding of Christ.)

More recently on this blog Earl Doherty stated in relation to this 1920’s French mythicist (again my emphasis):

Prior to Wells, the mythicist whose views were closest to my own was Paul-Louis Couchoud who wrote in the 1920s, though I took my own fresh run at the question and drew very little from Couchoud himself.

I have recently acquired a two volume English translation of Couchoud’s work titled The Creation of Christ: An Outline of the Beginnings of Christianity, translated by C. Bradlaugh Bonner and published 1939.

Today I did a very rough and dirty bodgie job of scanning the introductory chapters of this book and making them word-searchable. But if you are not a fuss-pot for perfection and are curious about how Couchoud opens his argument I share here the opening pages of this two volume work. Continue reading “Earl Doherty’s forerunner? Paul-Louis Couchoud and the birth of Christ”