I have almost completed reading First Footprints: The Epic Story of the First Australians by Scott Cane. It is based on the recent TV series of the same name. So few Australians know much about the history of aboriginal Australia and reading/viewing a work like this inspires one to call out for making such knowledge a core part of every Australian school’s curriculum. It not only has the potential to encourage an unprecedented respect for our indigenous brothers and sisters, but also the hope of deepening our understanding of the way our environment changes and challenges its inhabitants over the long term.

I have almost completed reading First Footprints: The Epic Story of the First Australians by Scott Cane. It is based on the recent TV series of the same name. So few Australians know much about the history of aboriginal Australia and reading/viewing a work like this inspires one to call out for making such knowledge a core part of every Australian school’s curriculum. It not only has the potential to encourage an unprecedented respect for our indigenous brothers and sisters, but also the hope of deepening our understanding of the way our environment changes and challenges its inhabitants over the long term.

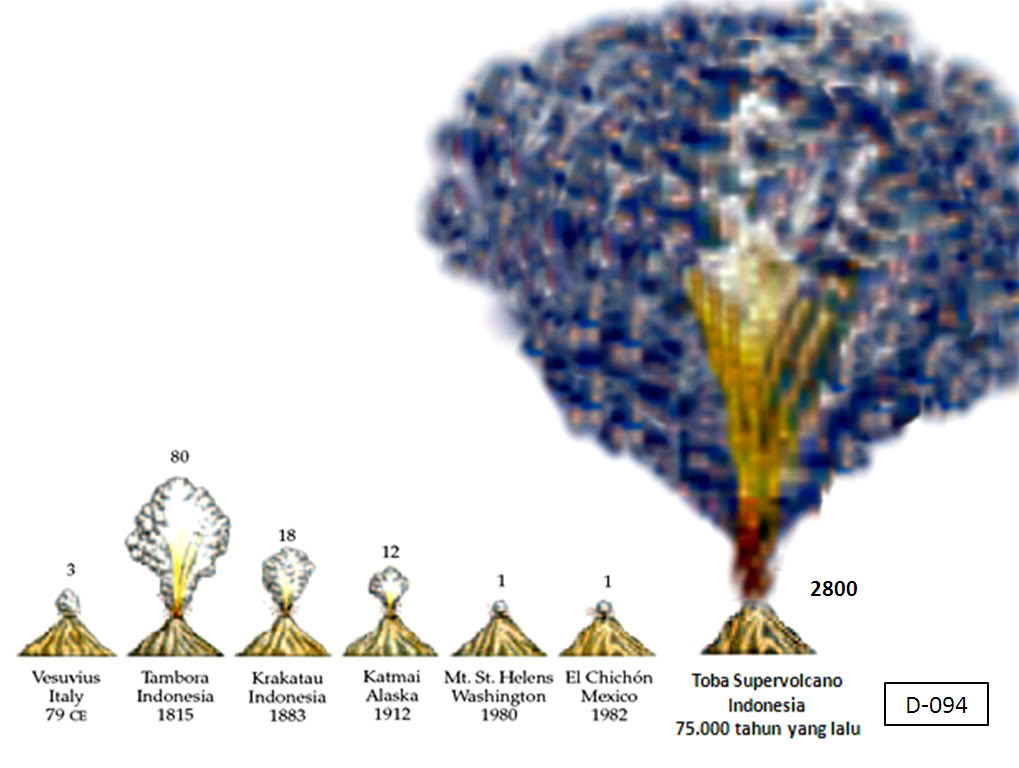

The story starts with the staggeringly incomprehensible eruption of Mount Toba in central Sumatra, Indonesia, around 74,000 years ago. It dropped up to three metres of ash over much of India and Pakistan. It pushed out a 40 metre tsunami that was registered in the English Channel. “It blew 3000 cubic kilometres of volcanic rock into the air, beyond the world’s atmosphere and at least 40 kilometres into space at a rate of about 10 million tonnes per second.”

Darkness covered much of the world; forests turned to grassland; extinctions occurred; temperatures fell; and a world already facing droughts from an emerging ice-age plunged into even more devastating “mega-droughts” and perhaps the coldest the earth has ever been in the past 125,000 years.

The human population suffered horribly — reduced, perhaps, to a population of 50,000 people in which there were as few as 4000-10,000 breeding females. (p. 13)

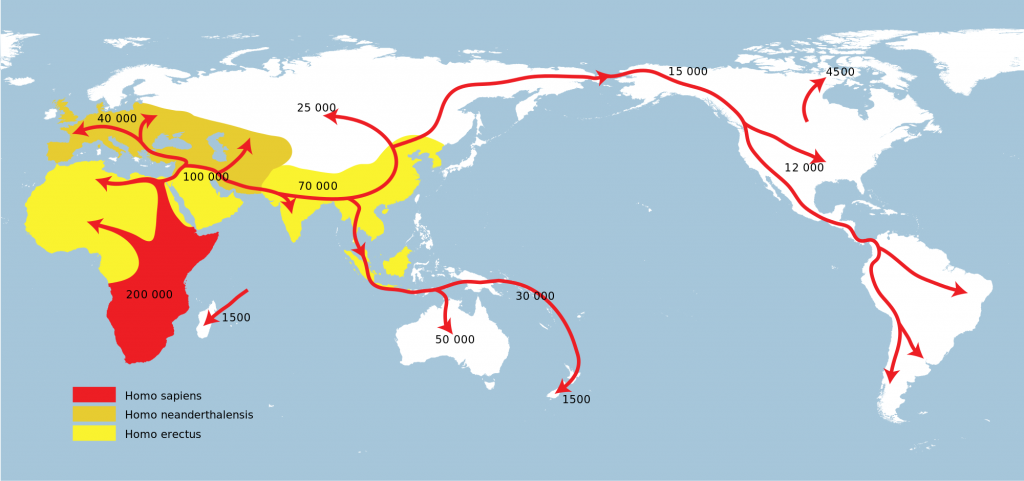

The first evidence for human settlement in Australia comes in the wake of this event. Human survivors downwind and east of the eruption may have been the first to arrive; or perhaps the first settlers belonged to those who began their trek from Africa and followed the southern Asian coastline till they reached here. The founding population of Australia came in a wave of around 1000 people — according to genetic research.

They were met with megafauna: 3 metre high kangaroos, 7 metre long “lizards”, 2 metre high “geese”, herds of “wombats” standing 2 metres at the shoulder, lions lurking in trees ready to pounce on prey below. One way to control wildlife threats was to burn the forests and long grass around their dwellings and so remove the cover for the predators. Aborigines have continued to use fire for the same purpose into modern times — clearing out the long grass to remove threats of snakes and expose the holes where edible goannas hid. Later more sophisticated “fire-farming” was developed and changed much of the landscape of Australia into liveable “gardens” of plots that were regularly recycled for hunting and foraging.

I’d love to talk also about the nomadic feats of these early colonizers, all that we can learn about them from their rock art, and the way they used “Dreaming” (collections of tales of myths) to hold their communities together and to even guide them across vast distances like topographical maps. But the real reason I began this post was to talk about something of interest to those of us who have grown up with the Bible as our “foundation stone” of “true myths”.

The Dreamtime and the Flood Myths

18,000 to 15,000 years ago retreating glaciers ushered in a “wholly new” (Holocene) era of a warmer and wetter world. Sea levels rose. Continue reading “Universal Floods and Australian Dreamtime Myths”

Physicist

Physicist