I am continuing here with my responses to criticisms raised on the earlywritings forum against the proposal that the first biblical texts were composed as late as around 270 years before Christ. (I had looked forward to continuing the discussion on that forum until I lost confidence in the sub-forum’s promise to be an “academic discussion” for reasons which included the removal of some of my responses without notice.)

The next criticism I addressed was as follows:

In the [opening post] it was claimed that Elephantine remains indicated “that Persian era Jews knew nothing of the Pentateuch.” Not so. Rather, *some* Egyptian Aramaic writers asked *others* for advice about Torah. That does not necessarily indicate that there was no Torah, anywhere, then, though it does suggest that that minority, on an island in Egypt, did not have a written copy of Hebrew Torah and also the ability to read and interpret it.

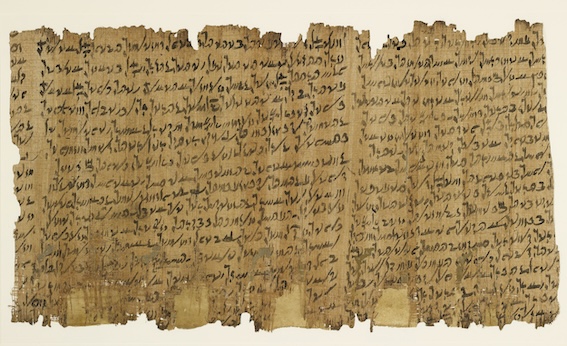

So let’s look at those “Elephantine remains”.

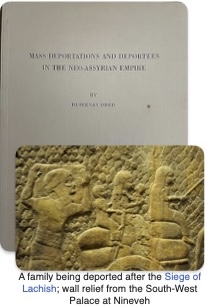

One of the strongest items of evidence that I believe refutes (it is more than an “argument from silence”) the existence of any form of practised Judaism or Biblical religion as we understand it before the Hellenistic era is a cache of documents from a Jewish, or more correctly Judean, military colony settlement in Egypt during the Persian period. We are talking about the island of Elephantine, 400s BCE.

One of the strongest items of evidence that I believe refutes (it is more than an “argument from silence”) the existence of any form of practised Judaism or Biblical religion as we understand it before the Hellenistic era is a cache of documents from a Jewish, or more correctly Judean, military colony settlement in Egypt during the Persian period. We are talking about the island of Elephantine, 400s BCE.

According to the Bible’s narrative the Persian period was the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, the return of Jews from Babylon to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the temple. If during the Babylonian exile the Jewish people had begun to turn away from idolatry and pine for a return to their homeland it was under the Persian rulers that their wishes materialized — according to the conventional wisdom. It is almost universally understood that the Jewish religion that we meet in the time of the Maccabee wars against the pagan Syrian domination and then again in the time of Jesus all took shape under the benign, even supportive, rule of the Persians.

That’s the prevailing view of the origin of Judaism. When the exiles returned to Jerusalem and the Persian province of Jehud they soon enough set about rebuilding the temple and keeping the Torah laws of sabbath observance, shunning mixed marriages, refusing any images of god, keeping Passover and other festivals, animal sacrifices and so on.

That is the Bible’s portrayal of what happened.

What, however, does the archaeological evidence tell us?

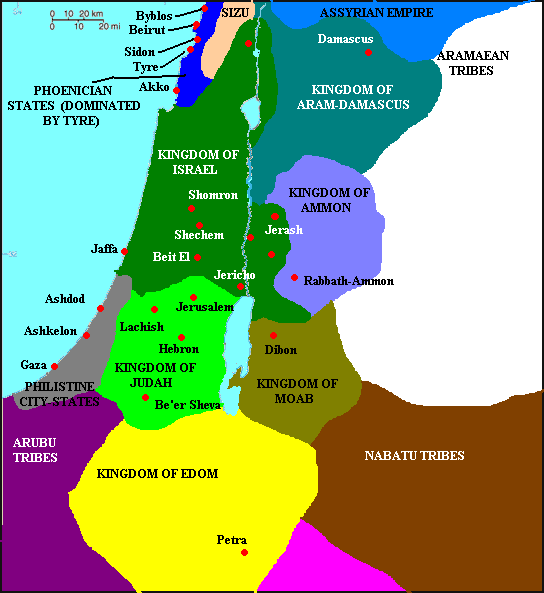

That was the slide archaeologist Israel Finkelstein presented to illustrate what has been found in the Persian province of Jehud (Judea) for evidence of a literate culture (From a 2022 conference).

If there is zero evidence from the Persian province of Jehud (Judea) for a “writing culture” we do have evidence from the Egyptian colony of Elephantine that informs us about more than just the local observances of the “Jews”. It gives us information about the religious outlook of their ethnic cousins in Judea as well. (In a future post I’ll explain in more detail why I write “Jews” in quotation marks: for now I will say only that the term is misleading insofar as it brings to mind people who practised some form of Biblical religion when in fact the people being discussed practised a religion that was far removed from anything biblical.)

The first question that is likely to come to mind is this: How relevant can the evidence from a Judean settlement in southern Egypt be as a source for what was practised in Judea?

Good question. Following are some answers:

Elephantine was not an isolated outpost that was out of touch with the culture and religion of Jerusalem.

Elephantine is representative of Persian era “Jewish” religion

[T]he Elephantine community stood in contact with Jerusalem. Although Elephantine was located on the traditional southern border of Egypt, it was not an isolated outpost on the fringe of the world. The Nile was navigable all the way from the Nile delta to Elephantine. A journey from Elephantine to Jerusalem might take approximately one month. In comparison, according to the Bible it took Ezra around four months to travel from Babylon to Jerusalem. In terms of travel time, the Judaeans in Elephantine were much closer to Jerusalem than was the priest-scribe who is often accorded great importance in the (re-)formation of Judaean religion in the Persian period. Whereas this may indicate potential contact and demonstrate that the historical-geographical conditions for travelling between Elephantine and Jerusalem were more favourable than those between Babylon and Jerusalem, it is also evidenced by documents from Elephantine that there was actually a two-way contact between Jerusalem and Judah (and Samaria). Not only did the Judaeans in Elephantine know the names of the tenuring governors of Judah and Samaria (in this case, even the names of the sons of the governor) and the high priest in Jerusalem…, they also wrote letters to them and even got a reply …. (Granerød 4)

and translating Knauf:

Elephantine was neither marginal nor exotic in 5th century Judaism. The Elephantines called themselves “Jews” (yhwdy’) and were called so by the Persian, the semi-autonomous Jerusalem and Samarian authorities. No one questioned their Jewishness at that time, simply because they had no Bible and knew no biblical traditions. For the other Jews were no different. (Knauf 182)

The Bible speaks of Jerusalem-Babylonian ties in the Persian era but Jerusalem-Egypt ties were no less significant:

[T]he two biggest settlements of the Judean population outside the province of Yehud in the Persian Empire were located in Babylon and Egypt. . . . [T]ogether with Jerusalem and Babylon, Egypt, in the Persian period, was one of the three key locations of those people whose geographical and religious roots were in Judah. (Siljanen, 3f — I hope to post some of the detail from the evidence we have of the Babylonian “Jews” later.)

Accordingly, we learn more about the practiced religion of Judeans from Elephantine than we do from the Bible:

[T]he Elephantine documents are contemporary sources and probably even more representative of the lived and practiced Yahwism of the Persian period than are the biblical texts. . . . [T]he biblical sources are centred around the Jerusalem temple. They presuppose a centralisation of the cult of YHWH, or to put it differently, they seem to take a form of mono-Yahwism as the norm. This kind of mono-Yahwism centred around the temple in Jerusalem has also quite often in the scholarship been taken to be the default manifestation of Yahwism in this particular period. However, from a historical perspective the big question is to what extent the biblical sources reflect Judaean religion beyond the milieus of the authors and the milieu of those who passed on the biblical tradition. (Granerød 5)

Another scholar confirms the view that “the situation at Elephantine [is] actually representative of many — if not most — portions of contemporary Judaism”:

[T]he texts discovered on the island cover the entire spectrum of official and private life and even encompass “aesthetic literature,” which demonstrates their recipients were fully integrated into broader social structures and dominant cultural and political circumstances. Such integration of the conditions at Elephantine into the larger cultural and political context of the ancient Near East around 400 BCE suggests a commensurability with or even analogy to the Judaism outside Elephantine rather than an exception to the rule — an assumption based on the biblical literature, especially the testimony of Ezra–Nehemiah. (Kratz 145)

and

[O]ne document . . . mentions Khnum [= god of local Egyptian] priests harboring enmity against the Judeans of Elephantine ever since a certain man by the name of Hananiah began to sojourn in Egypt. This Hananiah, a Judean ambassador, seems to have obtained from the Persian administration the official status of “Jewish garrison” for the Judeans on the island of Elephantine, whom he calls his “brothers”; this move may have aroused a certain rivalry with the local priests of Khnum. . . . .

[T]he mission of the ambassador Hananiah bears witness to close contact between the Judeans of Elephantine and those residing outside Egypt. In a certain sense, he constitutes living proof for the situation at Elephantine being actually representative of many — if not most — portions of contemporary Judaism. Although Hananiah was himself a Judean, coming from Judah or perhaps even the Babylonian diaspora, and should therefore represent biblical Judaism of the post-state period (to follow the usual scholarly explanation), he called the thoroughly unbiblical Judeans of Elephantine his “brothers” without any reservation whatsoever. Two conclusions proceed from this state of affairs. First, the Judaism of Elephantine existed not at the edge of the world but in close contact with its Jewish brothers even outside Egypt, as evident in the correspondence concerning reconstruction of the temple and in the mission of Hananiah. Second, the Jews in the motherland, i.e., Yhwh-devotees in Samaria and Judah, raised no objection at all to their brothers at Elephantine — at least as far as we can see — nor did they distinguish themselves from them in either essence or kind. (Kratz 139, 145)

Notwithstanding the views of these scholars who have studied and published in depth on the evidence from Elephantine, it remains the fact that “contemporary scholarship often considers the Judean colony at Elephantine an exception that proves the rule” (Kratz 143). The power of conventions and traditions!

You may have noticed in the above quotation the reference to “reconstruction of the temple” at Elephantine. The evidence culled from Elephantine informs us that the temple that the Judeans had built at Elephantine had been destroyed by local Egyptians. The correspondence produced in order to have the temple rebuilt has survived and has become a window through which we can observe the religious world of Judeans at that time.

Did Elephantine Judeans know of the Pentateuch?

I will allow quotes from various scholarly publications to answer that question. In the various quotations that follow there are different representations of the main god of these Judeans but it should be obvious when they refer to the more familiar Yahweh or YHWH.

** Judeans on Elephantine operated a temple that should not have existed according to the Pentateuch:

Biblical law, the Torah, permits but a single cultic place for Yhwh, namely the temple in Jerusalem (Deut. 12). According to this law, all other sanctuaries inside or outside of Judah are regarded as impure and devoted to other gods, which then warrants their destruction. The Judeans of Elephantine, however, did not bother themselves with this law. They operated a temple that should never have existed according to the Torah. (Kratz 138)

and

A few years later a letter was written from Elephantine to Samaria and Jerusalem requesting the rebuilding of the temple of Yahô after the priests of Khnum destroyed it . . . .

In Elephantine there was a temple dedicated to the veneration of Yahô. This temple is first referred to in the prescript of an early fifth-century letter written by Oshea to his brother Shelonam: “[. . . . . to the (?) t]emple of Yahô in Jeb.” (Becking 27, 34)

It was a “real temple” in every sense of the word, not a makeshift substitute for another supposedly “real” one in Jerusalem:

In short, the area in Elephantine set aside for the god YHW was a temple in all meanings of the word:

– it was a place where YHW’s immanence was thought to be found so that we may cautiously borrow a much later (and perhaps anachronistic) rabbinic term and say that the Judaeans in Elephantine believed the Shekinah (“dwelling”) of YHW was in his temple in Elephantine, and

– it was a place where it was also possible for humans to communicate and interact with YHW by means of sacrifices. (Granerød 107)

In case there remains any doubt…

The temple of Yaho was at the heart of the Jewish neighborhood, whereas the Babylonian Arameans had their houses in proximity to the temples of Nabu and Banit, and the Syrians lived around the temples of Bethel and the Queen of Heaven. (Toorn 95)

** The Judeans at Elephantine were not monotheists (Yahô is a form of the name YHWH or Yahweh):

The cult of Yahô was not, however, completely monotheistic. The deities Eshem-Bethel and Anat-Bethel are referred to in the so-called collection account for the Temple of Yahô. Comparable divine names are Anat-Yahô and Ḥerem-Bethel. . . . The inscriptions from Elephantine also refer to many other deities, such as Khnum and Nabû, El and Shamash, Bêl and Nergal, that were not part of the cult of Yahô itself.

In addition, several letters have been found that are written by people with theophoric names containing Yahô and still use a blessing formula with plural gods: “May all deities seek your well-being at all times.” . . .

This text implies that two deities, Eshem-Bethel and Anat-Bethel, were connected to the temple of Yahô in Elephantine. (Becking 34, 39, 40 — notice that the second quote above is informing us that people had names that included a form of “Yahweh” [theophoric names] — e.g. EliJAH, AdoniJAH, IsIAH, NehemIAH — so we can conclude that YAHweh was a favoured god of these people.)

and

several documents clearly show that Judaeans in Elephantine were by no means “monotheists” (Granerød 4)

“Logically”, it is argued, the Elephantine Judeans could not have been monotheists before they entered Egypt, either:

The Jews of Elephantine were not monotheists. This statement holds true even if ‘Anat-Yhw/Bethel and Herem(-Bethel)/Ishim-Bethel had not been brought with them from their Palestinian homeland, but had been adopted only in Elephantine . . . . Certainly, the triad of Elephantine could have been formed only in Egypt; but the presupposition to see in Yhwh a god among other gods, who can have a goddess for a wife and another deity as a child, must have been a preservation of the Elephantines and not merely acquired in Egypt. The opposite would be quite improbable in terms of religious psychology: monotheists usually consider themselves intellectually and/or morally superior to polytheists. (Knauf 184 translation)

And one more quote just to be sure:

the Elephantine Judaeans had no problem in recognising the cults of other deities for non-Judaean people. (Lemaire 62)

** Though some scholars insist that the Elephantine Judeans did not make images of their god Yahu (YHWH) there is no doubt that they did erect stone pillars to represent the deity and his wife:

In the letter to Bagohi requesting restoration of the temple of Yahô, Yedoniah mentions the demolition of the ʿmwdyʾ zy ʾbnʾ, “stone pillars that were there.” This detail has given rise to the assumption that the Israelite deity was represented by one or more standing stones in the temple at Elephantine. It should be noted that the Aramaic noun ʿmwdyʾ is in the plural, and therefore the pillage of several standing stones is implied. . . .

Both Anat-Yahô/Bethel and Ḥerem-Bethel would thus be interpreted as a female or male cult object, each regarded as a representation of Yahô/Bethel, a visible sign and a taboo object. The Yahô/Bethel cult in Elephantine was therefore not strictly aniconic. The form and nature of these images are unclear. (Becking 42, 47)

Further,

Mostly the divine presence materialised itself in divine cult images such as statues and standing stones. The cult images functioned as the terrestrial locus of divine presence. . . .

As far as Elephantine is concerned . . . the stone pillars (‘mwdy’ zy ,bn’) as a matter of fact referred to . . . an aniconic cult with each one of the standing stones representing a deity. . . . (Granerød 91, 110)

One scholar, however, is convinced that there were images of the deities as well:

This raises the question whether the cult of Elephantine could have been aniconic. . . . A strong argument for the existence of images of the gods before the destruction of the temple in 410 B.C. is provided by the donation list. . . . Because it was about Yhw’s temple, he is the addressee of the donations . . . But then Yhw gets only 126 shekels of the total amount, 70 go to Ishim-Bethel and 120 to ‘Anat-Bethel. It can hardly be a question of contributions for their livelihood – from an ancient oriental cult enterprise one can expect that it supported itself; also the amounts are much too high for that. Nor is it about the costs of the common roof; so it is most probable that the donations are intended for the restoration of the cult images. Then it becomes understandable why the ‘Anat, who is mentioned least in the documents, receives almost as much money as her husband: which god likes to have a dwarf as a wife? (Knauf 185 translation)

** Contrary to Pentateuchal laws that document in minute detail the procedures required for various kinds of animal offerings, they did not offer animal sacrifices:

Though common before the destruction of the temple and announced for the future in the petition, burnt offerings are explicitly excluded in later documents. Whether this limitation derived from the centralization commandment in Deut. 12, which prohibits any kind of offering to Yhwh apart from in the chosen cultic place, or whether it stemmed from Persian reservations remains unclear thus far. On the whole, the Judeans of Elephantine lived as Jews among the nations, untouched by biblical Judaism and its holy scriptures. (Kratz, 140f)

The evidence is not debated:

the Judaeans in Elephantine explicitly refrained from offering animals such as sheep, oxen and goats as burnt offering

……the Elephantine leaders wrote that animals “will not be made” … as burnt offering. . . .

[T]he official correspondence reflecting the attempts to get permission to rebuild the (second) temple of YHW [on Elephantine] after it was destroyed in 410 BCE … show that the Judaeans of Elephantine accepted the ban on animal offerings in the rebuilt temple. (Granerød 131, 132. 206)

But see the note on Papyrus Amherst 63 below that appears to come from a time after Persians had lost their influence. Animal sacrifices were understood to be an ideal at that time.

** The sabbath was a market or work day:

[O]ther ostraca refer to the Sabbath. However, these documents again evince no clear connection to the strictly biblical command for Sabbath (Exod. 20:8–11; Deut. 5:12–16), which the prophets supposedly demanded (Amos 8:5; Jer. 17:19ff.; Isa. 58:13–14) and Nehemiah reportedly established by force in Judah (Neh. 10:32; 13:15ff.). To the contrary, the ostraca provide no indication such stipulations were even known in Elephantine: individuals schedule various appointments on the Sabbath to pursue their labors and continue with their commerce. (Kratz 141)

This is not a secret among scholars:

… the Judaeans did not understand sbh (“Sabbath”) as a day of rest that fell on the last day of a seven-day week. (Granerød 208)

again

This ostracon indicates that on the day of the Sabbath, there obviously existed some trade in vegetables. (Becking 29 — although Becking here tries to save the biblical command by speculating that this might have been an emergency case)

Nonetheless, he does find other “emergency cases” and cannot deny the evidence:

A fragmentary letter that mentions bread also reads: “And now, bring to me on the Sabbath.” This inscription, too, seems to imply that (economic) activities could take place on a Sabbath. . . . . There are no indications that the Sabbath was the weekly day of rest. (Becking 30)

** The Pentateuch forbids Israelites to marry non-Israelites, but mixed marriages were normal in Elephantine:

Elephantine exogamous intermarriage was accepted. Various texts refer to such marriages. . . .

In Elephantine “mixed marriages” were accepted. (Becking 32, 52)

There is more than one scholarly witness on the record:

it is clear that the Judaeans practised and thus accepted intermarriage. (Granerød 49)

** So did these “Jews” of the Persian period know of the Pentateuch? Knauf is quite explicit in his answer to this question. The correspondence he refers to was occasioned by Egyptians in 410 BCE destroying the YHW temple and the Elephantine Judeans requesting help from Jerusalem:

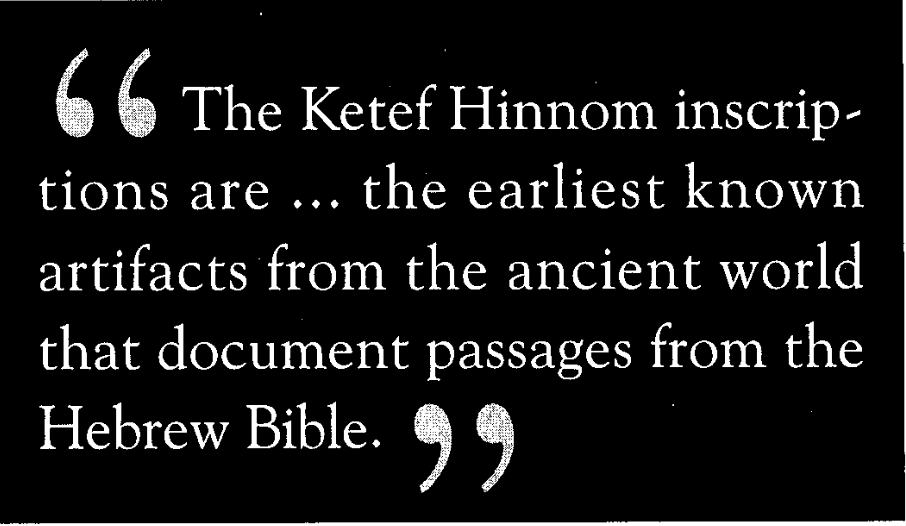

What is not attested at all in Elephantine, neither in the form of fragments nor in the form of mentions, is religious literature: rituals, cult legends, cult songs and prayers. This is all the more striking since the archive of the temple head is known. If, however, sacred scriptures were not kept there, but in the temple, then they are again missing from the list of losses. In this case, the Jerusalemites would have felt flattered if they had been asked for a replacement. The Elephantines, however, did not ask for new religious literature, and this in all probability because they had not had any old ones either. Priestly knowledge was obviously passed on orally; whether there were less profane reasons for this than the fact that perhaps no one in Elephantine could (any longer) write Hebrew, which might have been the language of the cult, must remain open. The fact is: in Elephantine they not only did not have a Bible, they also had no idea of and no need for one. (Knauf 185f, translation)

Papyrus Amherst 63

There is a papyrus from the Elephantine colony that contains a hymn in which Yahu is shown to love copious amounts of wine and the sacrifices of lambs. This papyrus (Papyrus Amherst 63) was purchased on the open market rather than being found in situ in Elephantine and was not translated until the 1980s, the problem being that its script was Egyptian while its language was Aramaic. The Papyrus is thought to date from the late fourth century, perhaps during the known hiatus in Persian control over Egypt. Recall that under Persian supervision animal sacrifices had been forbidden.

There is a papyrus from the Elephantine colony that contains a hymn in which Yahu is shown to love copious amounts of wine and the sacrifices of lambs. This papyrus (Papyrus Amherst 63) was purchased on the open market rather than being found in situ in Elephantine and was not translated until the 1980s, the problem being that its script was Egyptian while its language was Aramaic. The Papyrus is thought to date from the late fourth century, perhaps during the known hiatus in Persian control over Egypt. Recall that under Persian supervision animal sacrifices had been forbidden.

Biblical scholars have been aware of the existence of this mysterious papyrus since the 1980s, when two teams of scholars identified a song to Yaho in the compilation that seemed to be almost a copy of Psalm 20. Other parts of the papyrus prove to have references to the gods Nabu, Nanay, Bethel, and Anat. As experts already suspected in the 1980s, this compilation consists of literary traditions from the Aramaic-speaking diaspora communities in Persian Egypt. In Elephantine and Aswan, there had been temples for Yaho, Bethel, and Nabu — the very gods who are addressed in the ritual songs of the Amherst papyrus. . . .

At Elephantine, finally, Yaho was believed to be a deity with a Dionysian side. He drank wine in large quantities and liked to hear music. The sacrifice of fine lambs pleased him. In the three Yahwistic psalms of the Amherst papyrus, Yaho is depicted as a bachelor. At Elephantine, however, he had a partner called Anat (Anat-Bethel or Anat-Yaho . . .), also known as the Queen of Heaven. In view of the love lyrics between Nanay and Herem-Bethel in the Amherst papyrus, the relationship between Yaho and his consort was hardly platonic. (Toorn 2, 107)

Toorn’s translation of the relevant section:

Hear me, our God!

Fine lambs (and) sh[ee]p

We will sacrifice for you among the Gods.

Our banquet is for you

Among the Mighty Ones of the people,

Adonai, for you,

Among the Mighty Ones of the people.

Adonai, the people will bless you.

Your annual offerings we will perform.

From the pitcher, saturate yourself, my God!Let it be announced forever:

“The Merciful One exalts the great,

Yaho humiliates the lowly one.”

They have mixed the wine in our jar,

In our jar, at our New Moon festival!

Drink, Yaho,

From the bounty of a thousand bowls!

Be satiated, Adonai,

From the bounty of the people!Singers wait upon the Lord,

The player of the harp, the player of the lyre:

“We will play for you

The song of the Sidonian lyre,

And our flutes resoundingly,

At the banquets of humankind.”

The Amherst papyrus further indicates that the Judeans at Elephantine were at least a mix of Judeans and Samarians or Samaritans, and both worshiped Isis or Ishtar alongside Yahweh:

Interestingly, there is only one section on the papyrus with an explicit emigration scenario: the “Samarian-Judean arrival” poem in col. xvii. In lns. 1–6, a band or troop of Samarians arrives before a king, who asks from whence they and their language have come. A young man replies, “I come from [J]udah; my brother has been brought from Samaria; and now, a man is bringing up from Jerusalem my sister.” In van der Toorn’s view, this passage describes the arrival of a troop of Samarians led by a Judean . . .

In addition, the “Throne of Yahō” that is asked to bless “from the South” in col. viii may be a reference to the temple of Yahō at Elephantine . . . . Finally, the remarkable importance given in the anthology to Nanay – the goddess worshiped across the Near East especially by Arameans, and identified with both Ishtar in Mesopotamia and Isis in Egypt – and the strategic placement of compositions about her, may have been a means to demonstrate the unity of a diverse Aramean community in an Egyptian context. (Holm 330)

–o0o–

There is much more to the evidence we have from Elephantine than I have covered above. I did not touch on the Passover or new moon festivals here. I hope to post more in the near future.

Becking, Bob. Identity in Persian Egypt: The Fate of the Yehudite Community of Elephantine. University Park, Pennsylvania: Eisenbrauns, 2020.

Granerød, Gard, and Granerod. Dimensions of Yahwism in the Persian Period: Studies in the Religion and Society of the Judaean Community at Elephantine. Berlin ; Boston: De Gruyter, 2016.

Holm, Tawny. “Papyrus Amherst 63 and the Arameans of Egypt: A Landscape of Cultural Nostalgia.” In Elephantine in Context: Studies on the History, Religion and Literature of the Judeans in Persian Period Egypt, edited by Reinhard G. Kratz and Bernd U. Schipper, 323–51. Mohr Siebeck, 2022. https://www.academia.edu/79082488/Papyrus_Amherst_63_and_the_Arameans_of_Egypt_A_Landscape_of_Cultural_Nostalgia_in_Elephantine_in_Context_ed_Kratz_and_Schipper_FAT_155_Mohr_Siebeck_2022.

Knauf, Ernst Axel. “Elephantine Und Das Vor-Biblische Judentum.” In Religion Und Religionskontakte Im Zeitalter Der Achämeniden, edited by Reinhard G. Kratz, 179–88. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlaghaus, 2002.

Kratz, Reinhard G. Historical and Biblical Israel: The History, Tradition, and Archives of Israel and Judah. Translated by Paul Michael Kurtz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Lemaire. Levantine Epigraphy and History in the Achaemenid Period (539-322 BCE): Lectures for 2013. Oxford: Oxford University Press UK, 2015.

Siljanen, Esko. Judeans of Egypt in the Persian Period (539-332 BCE) in Light of the Aramaic Documents. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Helsinki, 2017.

Toorn, Karel van der. Becoming Diaspora Jews: Behind the Story of Elephantine. Yale University Press, 2019.

My reply:

My reply: