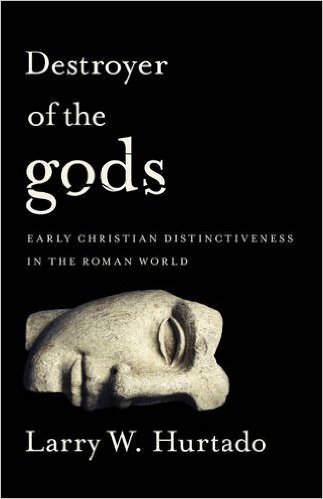

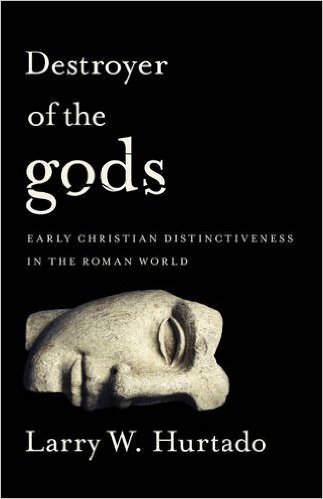

A steady stream of my RSS notices over recent weeks and months have alerted me to interest in a new book by Larry Hurtado, Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World. The title is dramatic enough. Search the term “destroyer of the gods” on Google’s Image search to see the dramatic scenarios it conjures. But the book is not about how Christianity “destroyed the gods” of ancient Rome (at least not directly) as the subtitle less dramatically warns.

A steady stream of my RSS notices over recent weeks and months have alerted me to interest in a new book by Larry Hurtado, Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World. The title is dramatic enough. Search the term “destroyer of the gods” on Google’s Image search to see the dramatic scenarios it conjures. But the book is not about how Christianity “destroyed the gods” of ancient Rome (at least not directly) as the subtitle less dramatically warns.

Throughout my reading a question that kept bouncing ungrammatically around in the back of my head was, “Who is this book written for?” My conclusion is that it is written primarily for readers who will indeed find the main title, destroyer of the gods, personally exciting and rewarding. Had I been a Christian of the conservative or evangelical sort when I read it I would have been tickled pink to identify myself with a religion that had the power to overthrow the entire pantheon of ancient Rome. The tone of the book is consistent with this message of the title:

Christianity’s “constellation of devotional practices is quite simply remarkable, even astonishing.”

Paul makes an “astonishing move” in the way he reinterprets the Old Testament for his own day.

The earliest Christians did not simply come to believe that Jesus had been resurrected, but far more, Hurtado drives home to readers that they held “the startling conviction that God had raised Jesus from death”.

Christianity “both focused on Jesus and had a sense of distinctive group identity” “from an amazingly early time”.

Christianity grew “remarkably” in its first two hundred years.

“The story of early Christianity is a remarkable phenomenon. . . It is simply the case that ‘no other cult in the Empire’ grew at anything like the same speed.”

Christianity grew “by power of persuasion, whether in preaching, intellectual argument, ‘miracles’ exhibiting the power of Jesus’ name, and simply the moral suasion of Christian behavior, including martyrdom.”

Christians “demonstrate the remarkable and admittedly unusual power of their own citizenship [of the kingdom of God”.

What was most “remarkable” in the Roman world was the Christian message that “there is one true and transcendent God . . . [who] loves the world/humanity” and actively sought the “redemption and reconciliation of individuals.”

The written outputs of Christians was also “remarkable” — “it is remarkable to have four extended accounts of Jesus’ ministry produced by as many authors and all within such a short period.” The commitment to produce the Christian writings required “strong commitment” and a “remarkable readiness” to do so.

The early Christian movement was identifiable and distinguishable particularly by the extraordinary reverence typically given . . . to Jesus along with God.

In discussing Christian worship practices in their Jewish context Hurtado uses the word “unique” near to two dozen times.

All of this emphasis on the “astonishing” and “remarkable” and “unique” is deliberate. Hurtado’s stated aim in writing the book is to shake readers from what he sees as their all too common complacency of taking so much about Christianity for granted and to appreciate how “astonishing”, “amazing”, “unique” and “remarkable” Christianity really was during its first three centuries of life. The message of the book is that early Christianity stood out like a bright shining light in the midst of a sea of benighted pagan religions and philosophical schools and primarily for this reason it was able to “destroy all other gods” and take over Western civilization.

Others will respond differently but the effort comes across to me as the strained efforts of an evangelist harnessing his scholarship for the service of preaching Christ. Just how strained, in my view, can be seen in his attempt to drive home “dramatic” implications of early Christianity’s exaltation of Jesus. Continue reading “Destroyer of the Gods”

Like this:

Like Loading...

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]

[Edit: When first published, this post credited Michael Bird instead of Michael Licona for this book. I can’t explain it, other than a total brain-fart, followed by the injudicious use of mass find-and-replace. My apologies to everyone. –Tim]