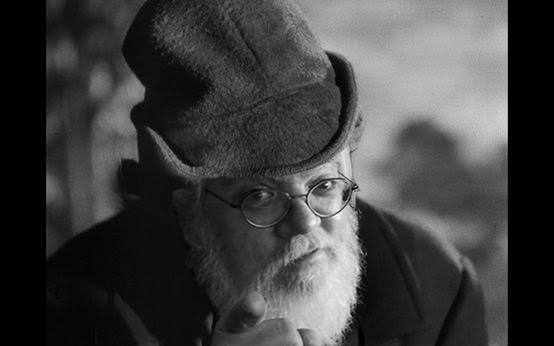

Robert M. Price sees himself as acting the role of the original Satan who was God’s envoy tasked with testing the true character of those who professed fealty to God. I’ll leave you to read his post where he explains the analogy. What interested me were the following sentiments:

Robert M. Price sees himself as acting the role of the original Satan who was God’s envoy tasked with testing the true character of those who professed fealty to God. I’ll leave you to read his post where he explains the analogy. What interested me were the following sentiments:

I have too much experience, much of it quite positive, with religion in general and Christianity in particular, simply to fight against it tooth and nail. It would be pathetic and quixotic. It would say more about me than about Christianity. I would have turned into a crazy, bitter ex-boyfriend. No thanks.

Ditto for me.

I have seen so much of Christians of all stripes and of Christianity in its many variations that I cannot pretend there is no good side to it. There is much to be loved, and I still love it. And this sentiment seems to me basic to any study of religion, period. You have to try to understand Islam, Buddhism, etc., from all sides including the inside. Unless you see what is loveable about it, you will never see why its adherents love it.

Mmm … I’m not quite in sync here. No, I can’t say I “love” any of it, still, though I am awed at the architecture of some of the older churches I’ve seen in Europe. But yes, one does need to try to understand religion “from the inside” in order to appreciate why people do love it — and that’s where I do think too many anti-theists fail. My perspective is more from the psychological side, though. What is it that happens in our brains when we imagine and pray to other-worldly beings? Such questions don’t lead us to love religion so much as they lead us to a deeper appreciation for our fellow creatures, for an acceptance of what we ourselves are made of. Maybe that has more to do with “self-love” or “self-understanding” and appreciation than “love for any aspect of religion”.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I can’t agree with the mythicist claim by those like Price that the Christology of Jesus at the earliest stages portrays Jesus as a dying/rising GOD. Rather, in Mark, Jesus is shown to be a fallible human prophet who cannot perform miracles in his home town. In Mark 6:4-5, we read:

4Then Jesus told them, “A prophet is without honor only in his hometown, among his relatives, and in his own household.” 5So He could not perform any miracles there, except to lay His hands on a few of the sick and heal them. (Mark 6:4-5)

If Jesus had the power of a God, he would have been able to perform miracles in his hometown. What was really going on was that YHWH was ultimately responsible for Jesus’ powers, and when and how they worked. Jesus’ miracles were from God acting through Jesus.

This is also illustrated in Mark when Jesus is portrayed as being filled by a power that is not simply controlled by the “WILL” of Jesus. Regarding the woman with the issue of blood, Mark writes in Mark 5:25-34:

25A woman who had had a hemorrhage for twelve years, 26and had endured much at the hands of many physicians, and had spent all that she had and was not helped at all, but rather had grown worse— 27after hearing about Jesus, she came up in the crowd behind Him and touched His cloak. 28For she thought, “If I just touch His garments, I will get well.” 29Immediately the flow of her blood was dried up; and she felt in her body that she was healed of her affliction. 30Immediately Jesus, perceiving in Himself that the power proceeding from Him had gone forth, turned around in the crowd and said, “Who touched My garments?” 31And His disciples said to Him, “You see the crowd pressing in on You, and You say, ‘Who touched Me?’” 32And He looked around to see the woman who had done this. 33But the woman fearing and trembling, aware of what had happened to her, came and fell down before Him and told Him the whole truth. 34And He said to her, “Daughter, your faith has made you well; go in peace and be healed of your affliction.” (Mark 5:25-34)

So, in this case Jesus did not “will” the woman with the issue of blood to be healed (he just realized after the fact that some of his power had been expended), but rather God healed the woman through Jesus (through a conduit).

Some mythicists appeal to Paul calling Jesus an “angel” to argue for a high Christology, but the Greek word there merely means “a messenger.”

1 Corinthians 8:5-6

5 For even if there are so-called gods, whether in heaven or on earth (as indeed there are many “gods” and many “lords”), 6 yet for us there is but one God, the Father, from whom all things came and for whom we live; and there is but one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came and through whom we live.

Jesus Christ helped to create all things and sustains the life of all human beings.

Doesn’t sound like an apocalyptic prophet to me.

The earliest Christian writer , Paul, does not regard Jesus as a miracle worker at all. Indeed, he scoffs at Jews for wanting to hear stories of miracles.

But the Gospels are not “Jesus at the earliest stages”. The mythicist view hinges on the observation that the Pauline epistles (and perhaps other comparable works) present the earliest attested Jesus. That much is basically agreed to by the majority of Bible scholars.

What makes mythicists different from most other researchers is the conclusion that Paul’s account of Jesus is radically different from Mark’s later euhemerism. This conclusion is based on a lot more than simply Paul using the word angel. e.g. Steven Carr above gives one such reference out of many.

P.S. Personally, I’m partial to the Simonian Origin hypothesis, which argues that the original version of Mark was a deliberate literary conflation of Jesus as pre-Gospel Christians would understand it with the life and times of Simon Magus/Paul. Thus, Jesus in the Gospels is a 1st century human teacher in Palestine because Simon of Samaria was a 1st century human teacher in Palestine.

“What makes mythicists different from most other researchers is the conclusion that Paul’s account of Jesus is radically different from Mark’s later euhemerism.”

That is somewhat putting words in [all] mythicist mouths and it’s also a loaded statement.

It’s possible that Mark’s (& other synoptic) accounts are not euhemerizations of Paul (as Carrier argues): it’s possible that Mark’s (& other synoptic) accounts developed independent of, and with the gospel authors not knowing, the Pauline accounts.

Jesus identifies himself as a prophet (Mark 6:4-5), and while different prophets had varying amounts of power (eg. Elijah bequeathed Elisha a double portion of his power to serve as his successor and superior), prophets were ultimately testaments to God’s power, not their own power. So, we see the superiority of Yahweh over the Egyptian Gods when Moses bested the sorcerers of Pharaoh. Likewise, we see the superiority of Yahweh over Baal when Elijah bested the prophets of Baal. Similarly, we see the superiority of Yahweh over Satan when God’s prophet Jesus defeats Satan’s demonic forces and the power of Sin. The point isn’t that Jesus was a God, but rather that he was God’s greatest human prophet who was given the purest expression of God’s power. If Jesus was a God and not merely a prophet, he would have been able to perform miracles in his home town, which he couldn’t (Mark 6:4-5).

One often comes across this claim in the scholarly literature but it rests upon a selective and tendentious reading of the gospel and it is not hard to find the reason. The model of Christian origins at the heart of most scholarship is the evolutionary view of man gradually being though of as a god.

But other scholarship that studies the literary nature of the gospels (and has no thought for the question of how Jesus came to be worshiped as god) very often shows us very clearly that the Gospel of Mark is written with theological meanings injected into its narrative. The Gospel of Mark makes no sense if read as historical narrative but makes ample sense when read as parable — as the author hints early on that it should be.

The two-stage healing by Jesus is not a sign of his human weakness but fits in with all the other dualities throughout the gospel that point to clear theological messages. Many scholars have noted that the double-healing reminds readers of the way the disciples only dimly understand who Jesus is at first and it is only later they see fully.

There are ample narratives throughout Mark’s Gospel demonstrating Jesus is God — like God he walks on the sea, and calms the sea, etc. One can make no sense of those passages if we read the healing episodes as an attempt to preserve some “real history”.

So, in this case Jesus did not “will” the woman with the issue of blood to be healed (he just realized after the fact that some of his power had been expended), but rather God healed the woman through Jesus (through a conduit). “God” rewarded the woman because she showed great faith, not “Jesus”. Jesus just discovered that he had been a vessel for God’s grace and power after the fact.

Another interesting point that can be derived about Jesus’ death from his desperate prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane is that Jesus did not believe it was NECESSARY for Jesus to die for God’s goal/plan to be realized: “Abba, Father,” he cried out, “everything is possible for you. Please take this cup of suffering away from me. Yet I want your will to be done, not mine. (Mark 14:36)”

We are all familiar with the narrative and the passages you cite. But your interpretation is one that I believe is against the grain of the gospel and opens up many unresolvable problems if we are to interpret it all consistently. Mark is not exploring the psychological thoughts or feelings of Jesus. Everything done is a re-writing of scriptures for theological lessons. You are reading into Mark a psychology or anthropology that is quite alien to his interests and the themes of his gospel — understandable given that many scholars do exactly the same because they need Mark to be the first narrative evidence for the historical Jesus.

“I can’t agree with the mythicist claim, by those like Price, that the Christology of Jesus at the earliest stages portrays Jesus as a dying/rising GOD.”

Plenty of believing scholars also say Jesus was portrayed as God from the start.

Agree with Hitchens. Religion poisons everything.

“Reconstructing God’s Answer To Jesus’ Prayer In Gethsemane:”

From Jesus’ desperate prayer in Gethsemane, we learn that Jesus, fundamentally, didn’t want to die, and on top of that did not believe he needed to die for God’s plan/goal to be realized:

36 “Abba, Father,” he said, “everything is possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will.” (Mark 14:36)

Jesus desperately begged God to spare his life. Whatever Jesus thought God said in response to this prayer, Jesus gained the courage to carry out his mission.

Jesus probably thought God told him that God would send a divine being to save him from the cross. Once he was on the cross, however, Jesus became convinced that God had abandoned him, and called out:

“Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” which means, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” (Mark 15:34)

Jesus was desperate for God to send him a divine rescuer, who he thought might be Elijah, the great prophet of old:

35When some of the bystanders heard it, they began saying, “Behold, He is calling for Elijah.” 36Someone ran and filled a sponge with sour wine, put it on a reed, and gave Him a drink, saying, “Let us see whether Elijah will come to take Him down.” (Mark 15:35-36)

The divine rescuer never showed up and Jesus died. Had God broke his promise to save Jesus? No!

Just as the masses didn’t understand the message of Jesus because he spoke in parables, Jesus didn’t understand that when God said in answer to his desperate prayer He would save him, it would not be through divine intervention, but rather glorious resurrection.

So basically when the Gospellers had Jesus predict he would be resurrected, they would be lying.

And when Paul said that Jesus was raised according to the scriptures, Jesus himself had never understood what the scriptures had said. Jesus himself had had no idea that the scriptures said he would be raised from the dead, probably because he was too stupid to understand what he read.

You are imputing a lot of modern psychologizing into Mark’s Jesus. The Gospel tells us nothing about Jesus’ inner thoughts. You can test your hypothesis that the author somehow was intending to convey all that you have said by asking what the rest of the gospel narrative and characterization would like like if that was his intent or interest.

But it is nonetheless very clear that Mark’s Jesus asks not to die. Beyond that we know nothing. We cannot say Jesus was “desperately begging” because if the author wanted us to think he was “desperate” we would expect to portray him fleeing the Garden and not staying around to get arrested. Clearly according to the narrative Jesus is not at all “desperate” in seeking to save his own life.

So we have a contradiction in the narrative. On the one hand we have Jesus asking not to die, but on the other hand we have him portrayed as deliberately placing himself in a position where he will be taken off to die.

That is where “historical” or “biographical” interpretations break down. Mark is not writing a bio or history of Jesus that is in any sense a realistic portrayal of any human life. He is writing a parable, a theological narrative that only makes sense as a theological symbol or message and makes no sense in “real life”.

DB, I can’t tell whether you’re just highlighting the implausibility of this pericope, or implying there was a mortal Jesus who actually had this experience. In any case, your supposition, that Jesus received an answer of any sort to his prayer, is pure conjecture unsupported by anything in Mark 14.

This is one pericope for which decidedly no ‘oral tradition’ could have originated from an historical event; the disciples slept while Jesus prayed in the Garden, and He was a bit too busy the next day to relate it to anyone. Rather than musing on was going on in the character Jesus’ head, we ought rather focus on what was on the mind of the author of Mark when they made up this story.

When Mark places the words “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” on Jesus’ lips, he is citing Psalm 22. This does NOT mean that Mark’s use of the words of Psalm 22 necessarily need to be interpreted in the exact sense that the words were in the original Psalm 22. The gospel writers were not necessarily staying with the “original sense” of bible passages when they cited them. For example, in Matthew 2:15, Matthew cites Hosea 11:1 (“Out of Egypt I have called my son”) to give pedigree to his story of Jesus’ childhood time in Egypt. But in Hosea, the word “son” refers to Israel, not to a child (let alone Jesus). So we need to look beyond the literal meaning of cited passages by gospel writers to determine what those citations meant to them.

Okay, I think I follow your logic: Jesus asks to be spared in 14:36, then in 15:34 seems surprised that he is left to die on the cross. But earlier (10:34), Jesus predicts his death and resurrection. The two are incongruous.

But I think this prima facie interpretation is wrong. For in GPeter, Jesus’ last words read: “My power, my power, thou hast left me,” and IMO this is an artifact tracing back to the original wording in Mark. Thus, the Christ spirit enters the man Jesus in 1:10-11, but abruptly departs, leaving the dying man Jesus shocked.

We do indeed need to look beyond the literal meanings of the words, but we also need to be sure we are not bringing in our own biases into our interpretations. What is needed is a study of the genre and how the text was put together. We need to study the whole text and interpret its parts within the larger context.

It is an implausible interpretation that claims Jesus was both wanting, hoping, praying to avoid death while acting in a way that was contrary to those hopes. That interpretation is inconsistent with every other detail of the Jesus we find in the Gospel of Mark.

The desperate prayers by Jesus in The Garden Of Gethsemane really speak against a “Trinity” interpretation of Jesus. If Jesus is one with The Father, why would he have to repeat the same desperate prayer three different times in Gethsemane? Why would Jesus need to pray at all?

Jesus’ last actions in Mark also speak against the idea that Jesus was welcoming of his death so he could calmly complete his mission: “With a LOUD CRY, Jesus breathed his last (Mark 15:37).”

You think it written after the Council of Nicea then? The Trinity is a whole lot later eisegesis, the author of ‘Mark’ wouldn’t know what you were burbling about, neither would the later gospel writers, the several authors of ‘John’ included. I think you should go back through Neil and Tim’s posts on how serious scholars in real disciplines go about their business, be it in Classics, History, Anthropology or Literature, and then sample the rest of this sites content. At the moment you aren’t doing much more than making stuff up.