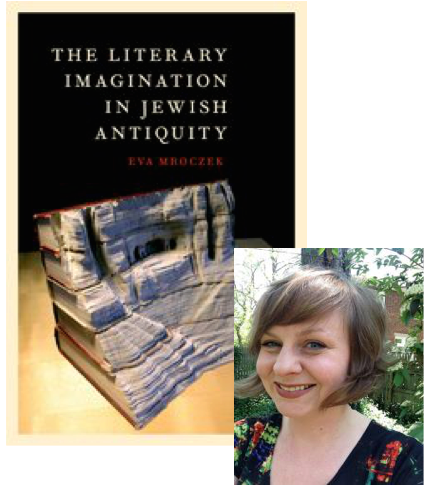

One of the books I am currently reading is The Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity by Eva Mroczek and I was intrigued by her discussion of how the scholarly community have debated the historicity of the “Teacher” who speaks powerfully of his experiences in the Thanksgiving Hymns of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Many scholars have identified the Teacher of Righteousness (otherwise known from the Damascus Document) as the author of these hymns. Notice, for instance, the introduction to the Thanksgiving Hymns by Wise, Abegg and Cook:

One of the books I am currently reading is The Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity by Eva Mroczek and I was intrigued by her discussion of how the scholarly community have debated the historicity of the “Teacher” who speaks powerfully of his experiences in the Thanksgiving Hymns of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Many scholars have identified the Teacher of Righteousness (otherwise known from the Damascus Document) as the author of these hymns. Notice, for instance, the introduction to the Thanksgiving Hymns by Wise, Abegg and Cook:

The intensely personal tone of the songs known commonly as Thanksgiving Hymns stands in sharp contrast with the rest of the scrolls. The author speaks of himself in the first person and recounts an agonizing history of persecution at the hands of those opposed to his ministry. In addition, the writer describes having received an empowering spirit granting him special insight into God’s will (1QH3 4:38), opening his ears to wonderful divine mysteries (9:23), using him as a channel of God’s works (12:9), and fashioning him as a mouthpiece for God’s words (16:17). Indeed, in col. 26, he claims that no one compares with him, because his office is among the heavenly beings. These are bold affirmations for any leader, reminiscent of various messianic claimants of both ancient and more recent history.

The unique personal presentation of the work and the self-conscious divine mission of the author have led many researchers to conclude that the psalms were written by the Teacher of Righteousness himself. Some students have attempted a more refined analysis in order to isolate “true” Teacher psalms at the center of the collection (cols. 10—16 according to one, 13—16 in the eyes of another; see Hymns 10—13,15—20,23), noting that the themes of personal distress and affliction as well as the claim of being the recipient or mediator of revelation are especially strong here. Only one thing is sure: the debate will continue.

Michael Wise, Martin Abegg Jr, and Edward Cook, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation, 2005. pp. 170-71.

Eva Mroczek is writing about literary/philosophical character of Ben Sirach and finds a parallel with the Teacher of Righteousness who is sometimes said to be the author of the Thanksgiving Hymns among the Dead Sea Scrolls. From pages 98 and 99:

Another example of such a rhetorical strategy is the so-called Teacher Hymns in cols. 10-17 of the Hodayot or Thanksgiving Hymns from Qumran. These first-person compositions have been read by some Qumran scholars32 as the ipsissima verba of the Teacher of Righteousness, an enigmatic figure who appears as a founder and leader of the sectarian community in some Qumran texts. The hymns, then, were imagined to be the creative autobiographical work of this putative individual, and were mined for information about this mysterious figure’s life. For example, Michael Wise has extracted from these hymns not only data about the Teacher’s life, persecution, and exile but also insights into his spiritual life—and even his name.33

But over time, as Max Grossman has shown, scholars began to question the idea that the Teacher of Righteousness is the “author” of these texts—that this figure is a historically locatable individual who can be imagined as an individual creator of the textual products of the Qumran community.34 With regard to the poetic Thanksgiving Hymns, it is doubtful that they can be used to reconstruct the historical and interior life of a specific individual. An excellent critique of the tendency to read the Hodayot as autobiography comes from Angela Harkins,35 who argues that such a reading is rooted in Romantic ideas of individual authorship that are foreign to Jewish antiquity. . . .

But no specific historical figure can be reconstructed from poetic hymns: they use familiar images and literary tropes, including first-person references to suffering and persecution that are not to be understood as biographical accounts of specific historical experiences. The “I” of the hymns can, instead, be understood in other ways . . . . The first-person voice is perhaps representative of the “office” of an inspired community leader and the ideal, exemplary teacher, rather than reflective of a specific historical personality.37 Or, as Harkins suggests, it is a “rhetorical persona” to be actualized by the reader in ritual performance: the reader embodies the “I,” and the text becomes an “affective script for the reader to reenact.”38

Okay, time to check out some of those end-notes. Continue reading “The Teacher of Righteousness and Understanding the Authority of Fiction”

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Bible’s ethics are not for our time. They represent an age when policies like those of Trump’s “extreme vetting if immigrants” were whitewashed as inspirationally loving.

The Bible’s ethics are not for our time. They represent an age when policies like those of Trump’s “extreme vetting if immigrants” were whitewashed as inspirationally loving.