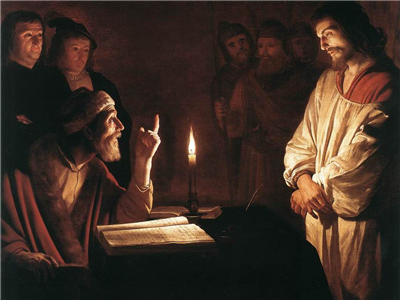

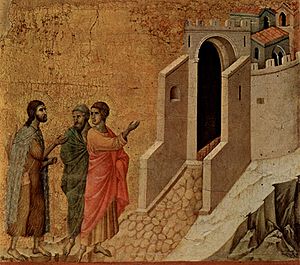

The author of the third gospel tells the well-loved post-crucifixion story of two disciples walking on the road to Emmaus. Along the way they meet a stranger (Jesus, incognito) who asks them what’s going on.

One of them, named Cleopas, answered and said to Him, “Are You the only one visiting Jerusalem and unaware of the things which have happened here in these days?” (Luke 24:18, NASB)

Here, Cleopas (Κλεόπας) makes his first and only appearance in the canonical gospels, unless you believe the character named Clopas in John’s gospel is the same person.

Now there stood by the cross of Jesus his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene. (John 19:25, KJV)

Notice that the Authorized Version manages to hide the fact that the underlying Greek contains a different name. The Textus Receptus says κλωπα, but the KJV translators have pre-harmonized John with Luke, a fact the lay reader would scarcely suspect.

(From this point forward, I’ll use the modern transliteration for Kleopas and Klopas.)

Virtuous Harmonization

Some have even argued that Alphaeus, Klopas, and Kleopas are all the same person, but you would have to dive pretty deeply into the upside-down world of the apologists to believe that. Harmonization here, given the scant information we have about the name and the characters portrayed in the gospels, is unwarranted.

We might even suspect that Luke invented the name, given the lack of attestation to it in contemporary literature and the uncertainty surrounding its etymology. Some authorities have presented the argument, not without merit, that Kleopas is short for Kleopatros, the masculine form of Kleopatra, a name that means something like “glory of the father.” As an example, they note that the nickname of Herod Antipater was “Antipas.” On the other hand, several authors have claimed that the names Kleopas and Klopas both come from the same Aramaic source, which seems possible, but tough to prove.

Fictional Characters

Richard Carrier, in On the Historicity of Jesus, says Luke probably invented the name and then goes further, claiming that it means “Tell All.” He writes: Continue reading “The Unclear Origins and Etymology of Kleopas (Κλεόπας)”

Until recently, I had never heard of the

Until recently, I had never heard of the