As you may recall from the first part of this series, Maurice Halbwachs wrote an important and detailed treatise on social memory and its relation to memorialized places (les localisations), which he called The Legendary Topography of the Gospels in the Holy Land: A Study of Collective Memory (La topographie legendaire des evangiles en terre sainte: Etude de memoire collective). In it, he chronicled the succession of Christians who memorialized various key places in Palestine: Nazareth, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, etc. Pilgrims, as well as those who could only imagine those places, combined the shared memory of events in the gospels with the ritual observance of those events within the social framework of their religion.

O, little town of Bethlehem

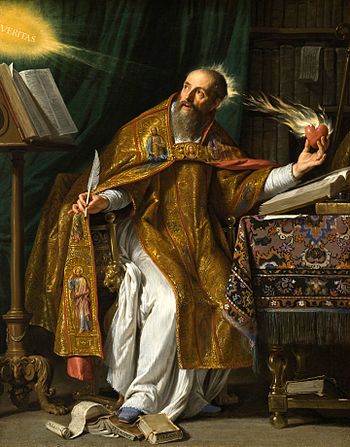

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

[Note: Edited on 20 April 2015. The earlier version erroneously said that La topographie was unfinished and published posthumously. That is incorrect. It was, rather, the work entitled La mémoire collective (1950), which was published after Halbwachs’s death in Buchenwald. We need to be careful not to confuse the English translation, The Collective Memory, with On Collective Memory. The latter is a collection, consisting of excerpts from Les Cadres Sociaux de La Memoire (The Social Frameworks of Memory) and the Conclusion (only) of The Legendary Topography of the Gospels.]

I must stress two points at the outset. First, for Halbwachs, the individual recollections of the disciples (imperfect, distorted, and incomplete as they may have been) formed the basis of the collective memory of later Christians. History, as we understand it today, is the product of critical research, and we shouldn’t confuse its results with our study of the collective memory of Christianity. Halwachs writes:

Collective memory must be distinguished from history. Historical preoccupations such as we think of them, and which each author of a work of history must be concerned with, were alien to Christians of those periods. It is in the context of a milieu comprising believers devoted to their religion that the cult of the holy sites was created. Their memories were closely tied to rites of commemoration and adoration, to ceremonies, feasts, and processions. (Halbwachs, 1992, p. 222)

How still we see thee lie

The second point we should keep in mind is that the work in French contained extensive notes by the author, with each chapter representing a different locale. The English version omits these earlier sections. Coser explains in a footnote:

The whole thesis and documentation of La topographie legendaire des evangiles en terre sainte: Etude de memoire collective is found in the conclusion, which has been translated in full. Earlier chapters are preparatory in character, discussing sources, documentation, and the like. They are primarily of interest to specialists in the area, and have not been translated here. (Halbwachs, 1992, p. 193, emphasis mine)

Anyone seeking to engage Halbwachs’s conclusions and criticize them needs to take those words to heart. It struck me after writing my first post on the Memory Mavens that I had perhaps been too harsh with Barry Schwartz. After all, according to Anthony Le Donne, he is peerless: Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 3: Bethlehem Remembered”