Explorations into why we believe and think the way we do should be shared as widely as possible and not restricted to scholarly publications. Hence these posts. (They cover ideas that we have presented before in different ways as they derive from different researchers, but slightly different perspectives on the same fundamental concepts can deepen our understanding of the matter.)

In the previous post we began with the point that we have two types of beliefs: reflective and non-reflective. Here we identify where these different types of beliefs come from. We will see in future posts how this model explains why belief in gods and spirits is in effect universal.

Where Non-Reflective Beliefs Come From

We are not taught everything we know. We are born with a brain that comes pre-packaged with a set of tools that enable us to make reliable inferences about how our world works.

These mental tools automatically and non-reflectively construct perhaps most of our beliefs about the natural and social world. Non-reflective beliefs arise directly from the operation of these mental tools on inputs from environment. The vast majority of these beliefs are never consciously evaluated or systematically verified. They just seem intuitive, and that is usually good enough. (Barrett 182)

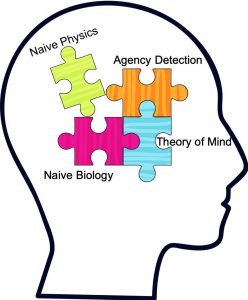

We focus on four of these mental tools.

Our Naive Physics Tool

Even as infants we “know” that physical objects:

-

- tend to move on inertial paths

- cannot pass through other solid objects

- must move through the intermediate space to get from one point to another

- must be supported or they will fall

Our Agency Detection Tool

-

- automatically tells us that self-propelled and goal directed objects are intentional agents

Our Theory of Mind Tool

Theory of mind gives us non-reflective beliefs concerning the internal states of intentional agents and their behaviors:

-

- agents act to satisfy desires

- actions are guided by beliefs

- beliefs are influenced by percepts

- satisfied desires prompt positive emotions

Our Naive Biology Tool

The Naive Biology “device” generates non-reflective beliefs about living things:

-

- animals bear young similar to themselves

- living things are composed of organic matter and not artificial substances

We do not need to be explicitly taught these things. We draw on our innate beliefs in them as part of our reasoning about the world around us.

These beliefs do not have to be “true”, either. For example, we non-reflexively “know” that rainbows display distinct colour bands but in fact they exhibit the full colour spectrum. But our innate beliefs about rainbows can lead us to forget the fact about rainbows that we learn in school. Our non-reflective biology processing system tells us that animals with similar gross morphologies and living in similar ecological niches are similar to one another, so it may be hard for us at first to grasp that possums, being marsupials, are more similar to kangaroos than they are to raccoons.

Where Reflective Beliefs Come From

Our minds are not blank slates. We cannot pour just any kind of information into an infant or child and expect them to assimilate it raw. All information that is presented to us is filtered by our non-reflective beliefs toolbox. Barrett uses the expression “reading off” our non-reflective beliefs. Our reflective beliefs largely derive from reading off our non-reflective beliefs. To take some examples of reflective beliefs from our first post:

-

- pumpkins are orange

- Michael Johnson holds the world record in the 200 meter dash

Our non-reflective beliefs about physical and living objects, inference-generating devices that we were born with, will cause us to dismiss claims that a new pumpkin has been developed to grow in sky-born clouds or that Michael Johnson can transfer 200 meters instantly. If we were asked if a raccoon is more similar to a cow or a possum we would need to resist our initial assumptions and choose instead to draw upon our reflective beliefs.

Several mental tools can work together to generate reflective beliefs. That is, we will “read off” a combination of devices together: agency detection, theory of mind, naive physics. An example:

For instance, if I observe a boy run into a room, turn right avoiding a step-stool on the floor, then turn left and collide with his brother’s carefully built model tower, I might form the belief that the boy wanted to topple his brother’s tower. Why?

Because his zig-zagging motion violates a purely mechanical (non-reflective) explanation of his action,

the Agency Detection Device registers this action as self-initiated and goal directed, and hence, intentional.

Theory of Mind tells me that intended actions arise from beliefs and desires. He wanted to do what he did.

These non-reflective beliefs converge upon the reflective belief that the boy wanted to topple his brother’s tower. In general, the more different non-reflective beliefs that converge on a particular reflective candidate belief, the more likely the reflective belief becomes held. (Barrett 184, my formatting)

Of course we can and we do often learn to over-ride our non-reflective beliefs. We lean to “consider the evidence” — but the evidence itself will always be filtered or processed by our mental tools.

Further, we never have direct access to evidence, but always to processed evidence or memories. We remember what someone told us a moment ago and we process the information through our innate filters that inform us what is reliable and “real” in this world.

Indeed, the more inferences we can bring into play from our various mental tools and apply to any proposition or idea, the more likely we are to reflexively believe that idea. That principle will become more important when we examine the origin of belief in gods in the next post.

So at what point does belief in gods enter this discussion?

Any account of why people believe in gods should start with how well such beliefs are supported by the non-reflective beliefs generated by naturally-occurring mental tools. Not all religious beliefs are anchored to non-reflective beliefs and arise because of them. For instance, that the Christian God is believed to be a trinity or non-temporal has little or no non-reflective foundation. Nevertheless, foundational religious beliefs such as the existence of gods that are intentional beings with beliefs, desires, and perceptual systems that guide their activities have a firm non-reflective foundation as I sketch below. (185)

“Below” in this case will be addressed in the next post.

Barrett, Justin L. 2007. “Gods.” In Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science, edited by Harvey Whitehouse and James Laidlaw, 179–207. Durham, N.C: Carolina Academic Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

3 thoughts on “Gods – 2 (An Anthropology of Religion Perspective)”