Who bewitched you? Paul demanded to know of the Galatians. He continued:

Before your very eyes Jesus Christ was written beforehand [προεγράφη, cf Rom. 15:4] as crucified.

Max Wilcox suggested (with some diffidence) at least the possibility of such a translation back in 1977 in an article published in the Journal of Biblical Literature. The remainder of this post draws a few key points from a mass of fascinating details in that article, “Upon the Tree”: Deut 21:22-23 in the New Testament”. It focuses on what Paul and other early “Christian” exegetes found written in the Scriptures through a midrashic type reading.

A few verses after that opening Paul “bizarrely” links Jesus Christ with the pronouncement of a curse on anyone “hanging on a tree” as per the law of Deuteronomy. Galatians 3:13:

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us. For it is written: “Cursed is everyone who is hung on a tree.”

quoting Deuteronomy 21:23

. . . anyone who is hung on a tree is under God’s curse . . .

Look at that Deuteronomy 21 passage in full and despair at trying to find any way Paul could have associated it with the crucified Jesus:

If a man has committed a sin worthy of death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his corpse shall not hang all night on the tree, but you shall surely bury him on the same day (for he who is hanged is accursed of God), so that you do not defile your land which the LORD your God gives you as an inheritance. (Deut 21:22-23)

Wilcox finds clues to the association in the verses leading up to Galatians 3:13. If we are aware of the Scriptures Paul has been alluding to in those preceding verses we can find the answer to why the Deuteronomic tree-hanging curse applied to Jesus.

Look at Galatians 3:8-9

Now Scripture, having seen beforehand that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, proclaimed the good news of this in advance to Abraham in the promise, “In you shall all the nations be blessed.”

So then, those who are ‘of faith’ are blessed with faithful/believing Abraham.

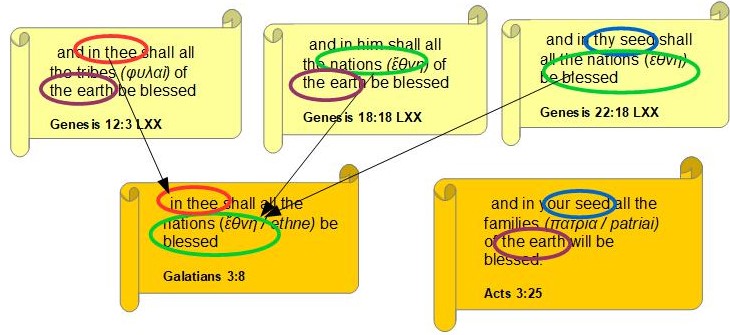

For Wilcox the above passage looks very much like a mixed quotation based on three passages in a Greek translation of Genesis (Notice that Peter is assigned a similar quotation in Acts: the major difference being that in Acts the stress is on “seed” while in Galatians it is on “you”, referring to Abraham.)

(Notice that Peter is assigned a similar quotation in Acts: the major difference being that in Acts the stress is on “seed” while in Galatians it is on “you”, referring to Abraham.)

Wilcox comments that Paul (and the author of Acts) are using a hybrid quotation to associate the promise to Abraham with the “nations”, the Gentiles.

Not only Genesis but Deuteronomy informs Paul’s thought

In Galatians 3:10 we begin to read a longer section of the cursing and blessing dichotomy. This motif comes from many passages throughout Deuteronomy. Galatians 3:10 even directly quotes Deuteronomy:

| Galatians 3:10 | Deuteronomy 27:26 |

| . . . for it is written, “Cursed be everyone who does not abide by all things written in the Book of the Law, and do them.” | Cursed be he that confirmeth not the words of this law to do them. . . . |

But why does Paul veer towards the “cursed is everyone hanging on a tree” passage when that passage is surely meant to apply to blasphemers and other sinners of the worst kind?

| Galatians 3:13 | Deuteronomy 21:22-23 |

| Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, “Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree”—” | And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is cursed by God. You shall not defile your land that the LORD your God is giving you for an inheritance. |

I need another post to address the evidence properly, but Wilcox points to a wide range of early translations or versions of this Deuteronomy passage to demonstrate that it caused quite some debate among early Jewish interpreters. Did the original Hebrew mean the victim was cursed by God or cursed in the eyes of God, or had he himself cursed God so that was why he was executed and strung up on a tree? Most of our sources further suggest, as we read in the above translation, that the criminal was executed first and then his corpse was hung on a tree. But we know from the Temple Scroll, 11QTemple 64:6-13 and possibly 4QpNah 3-4; 7-8, as well as the rabbinic Peshitta on Deuteronomy 21:22-23, that other interpreters read and wrote the passage as putting a living person on a tree; that is, to crucify him. I’ll post the details later. Further, Wilcox demonstrates in detail that Paul’s quotations of Deuteronomy and Genesis are very likely from a Greek translation of the Jewish Scriptures now lost to us. The quotes not only in Galatians but also in Acts and 1 Peter all appear to rely on a Greek translation other than the Septuagint.

But back to the Deuteronomy 21:22-23 — reading it in a version no longer extant, one which suggests that a living person was hung on a tree to die.

The last line of that section speaks of “an inheritance”. Paul uses the same word later in Galatians 3:18. That sentence alludes to Genesis and the promises God made to Abraham to inherit the land.

So Paul, with Deuteronomy in his thoughts, is reminded of the Genesis promise to Abraham at this point.

More than that, even the words “on a tree” bring to mind a vital episode in Abraham’s life and one that sealed the promise given to him because of his faith in God and righteousness in obeying the command to offer his beloved son as a sacrifice.

The Greek word for tree in Deuteronomy is the same word for wood in Genesis 22:6-9 — ξύλου (xylou)

6 And Abraham took the wood of the burnt-offering, and laid it upon Isaac his son; and he took in his hand the fire and the knife; and they went both of them together. 7 And Isaac spake unto Abraham his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I, my son. And he said, Behold, the fire and the wood: but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering? 8 And Abraham said, God will provide himself the lamb for a burnt-offering, my son: so they went both of them together.

9 And they came to the place which God had told him of; and Abraham built the altar there, and laid the wood in order, and bound Isaac his son, and laid him on the altar, upon the wood.

It’s worth quoting Wilcox at some length:

In Genesis 22 it is found in the plural ξύλα . . . for the wood of the burnt-offering and, more specifically, in 22:6 Abraham is depicted as taking the wood and loading it onto Isaac his son. Genesis Rabba comments on this, “like one who carries his cross . . . upon his shoulder.” A moment later Abraham is shown building an altar and setting out the wood upon it; he then binds Isaac and puts him “upon the altar, on top of the wood” . . . . In the NT model, in the fulness of time another comes to the place of sacrifice, carrying his “wood”/“cross” (cf. John 19:17), and is put upon it (cf. esp. 1 Pet 2:24 . . . ). We thus argue that behind the present context in Galatians 3 there is an earlier midrashic link between Gen 22:6-9 and Deut 21:22-23 by way of the common term … ξύλον …). That this has external confirmation we may see from (Ps.)-Tertullian, Adv. Iudaeos 10:6,

… Isaac, when led by his father as a victim, and himself bearing his own “wood,” was even at that period pointing to Christ’s death; conceded, as he was, as a victim by the Father; carrying, as he did, the “wood” of his own passion.

Nor is this the only place in Paul’s writings where the Isaac of Genesis 22 is identified as Jesus. We may cite, for example, Rom 8:32, which alludes to Gen 22:16 ….: “he who did not spare his own son, but handed him over for the sake of us all. . . .” May we perhaps dare to see one further reflection of Genesis 22 in Gal 4:6, “But because you are sons, God sent forth his son’s spirit into our hearts, crying out, Abba Father!” (Άββά o Πατήp; also Rom 8:15). This is not the place to go into a detailed study of this passage, but we may recall the address of the obedient Isaac of the Akedah to his father, as given in the Palestinian targums of Gen 22:6, 10, …. The spirit of God’s son cries out in our hearts — as did faithful Isaac of old — “(My) Father!” Or to put it another way: “. . . because you are sons, God sent his son’s spirit into our heart that by his spirit we too might cry out to him — like Isaac to Abraham — ‘Abba,’ i.e., ‘My Father.’”

(Wilcox, 98. Akedah is the Jewish term for the “binding of Isaac” episode in Genesis 22.)

In other words, we see a web of midrashic connections behind not only Paul’s epistle to the Galatians but in other details in the gospels, in Acts (in speeches by both Peter and Paul), in the catholic epistles of the NT. The link is not limited to a few passages in Paul’s works. In Acts 13:28-30 (also Acts 5:30; 10:39) — again Jesus is said to be crucified “on a tree” — presumably part of the same early exegetical tradition. If so, as Wilcox notes, we should find other evidence of such a tradition in the NT. We do:

1 Peter 2:24 combines Isaiah 53:12 with Deuteronomy 21:23

He Himself bore our sins in His body on the tree

Compare Isaiah 53:12 (who himself bore our sins) and Deuteronomy 21:23 (in his body upon the tree). A couple of verses earlier in the same letter we read of the emphasis on Jesus’ innocence despite his treatment. Thus 1 Peter 2:22 — “He committed no sin, and no deceit was found in his mouth” — is another passage taken from Isaiah, 53:9. But there is another connection even here with Deuteronomy 21:22 through the Septuagint or Greek translation. There the same word for “sin” is used.

Acts 13:28-30

28 And though they found no cause of death in him, yet asked they of Pilate that he should be slain. 29 And when they had fulfilled all things that were written of him, they took him down from the tree, and laid him in a tomb. 30 But God raised him from the dead:

The structure here follows that of Deuteronomy 21:22-23

| Acts 13:28-30 | Deuteronomy 21:22-23 |

| no cause worthy of death | committed a crime (sin) punishable by death |

| asked for him to be put to death (cf Acts 5:30; 10:39) | and he is put to death |

| they took him down from the tree | shall not remain all night on the tree |

| they laid him in a tomb | shall surely bury him the same day |

We find the same emphasis on the innocence of Jesus in Luke 23 and John 18 and 19. Pilate is noted as having explicitly announced that he found “no just cause of death” in Jesus.

Viewed this way we begin to see a closeness between Paul’s writings and the gospel narrative that might otherwise escape us. We have posted here at length on the Akedah, the scene of Abraham offering his son Isaac, and how that episode shaped the narratives in the gospels as well as certain ideas of Paul. See Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son (Levenson).

But if we grant Wilcox’s observations of Paul’s application of Deuteronomy 21:22-23 in a longer passage laden with motifs from Genesis and other parts of Deuteronomy, we begin to see an imagination that interpreted the Scriptures midrashically to see in their connections a picture of a Son of God, given up as was the son of Abraham, and whose death was by means of being hung from a “wood” or “tree”.

One seed = Christ

How, though, did Paul come to speak of Abraham’s seed as being found in the singular Christ? The Abraham promises in Genesis were made to Abraham’s seed in the sense of his millions of descendants.

Genesis speaks of Abraham’s seed in two ways: either as multitudes of descendants or as his son Isaac through whom the promise is to be fulfilled. (Ishmael is the “mistaken seed” — and Paul addresses that Genesis theme later in the same epistle to the Galatians.) Jewish tradition (recorded in rabbinic literature) in relation to Genesis 22:10 said

“The angels on high” refer to Abraham and Isaac here as “the only two righteous in the world.”

Isaac was the true son since Ishmael was the son of the slave. And if Isaac, the promised seed, carried the wood on which he was to be sacrificed just as Jesus carried the “tree” on which he was to be given up by his Father, — we begin to see closer conceptual links between Isaac and Jesus than we had earlier discovered in Levenson’s Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son.

Deuteronomy 21:22-23 contains more “mysteries” than I think many of us had imagined. In the minds of the shapers of the NT literature, it links to the Abrahamic promise of blessings and cursings; it links to the Abrahamic promise of possessing all nations (gentiles); it links to the righteous son’s means of death “on the wood/tree”; it contains the seeds of the narrative of Jesus carrying his cross, of him being declared innocent of any crime worthy of death by Pilate, and of being hung from the cross, and being buried that same day, and from there being resurrected.

Wilcox’s final paragraph contains some important considerations in any exploration of the origins of the Christian gospel or confessional message and one to which I expect to return in future posts:

Finally, we may note two procedural points.

First, the christological use of the OT in the NT is to be seen against the background of an active discussion of Scripture in the contemporary Jewish schools and forms part of that debate.

Secondly, in examining OT quotations and allusions in the NT we must treat all deviations from known textual traditions seriously and not be content to pass them off as due to the frailties of memory or mere casualness. Even where they do not seem to reflect a hitherto unknown textual tradition of the OT, they may well point to the existence and use of an exegetical tradition.

(Wilcox, 99)

Wilcox, Max. 1977. “‘Upon the Tree’: Deut 21:22-23 in the New Testament.” Journal of Biblical Literature 96 (1): 85–99. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3265329

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Paul’s decoder ring is the source of Christianity and he never even drank Ovaltine!

Great article. Learned so much from it and much to think about. Thanks, Neil.

“Before your very eyes Jesus Christ was written beforehand [προεγράφη, cf Rom. 15:4] as crucified.”

This is a notoriously difficult word salad from Chef Paulus. It usually says, “publicly portrayed as crucified,” giving the bizarre impression of a traveling passion play roadshow. Perhaps this would be a better translation:

“You foolish Galatians! Who has bewitched you? Before your very eyes Jesus Christ was already proclaimed as crucified.”

“Proclaimed” by Paulus himself, verbally from “the graphe” (Septuagint).

Liddell and Scott προεγράφη (“proegraphe”):

A. write before or first; write before or above; before-mentioned; write as a copy (pro- meaning “before, previous” and -graphe meaning “the scriptures”)

II. set forth as a public notice, “π. τι ἐν πινακίοις” Ar.Av.450; π. κρίσιν, δίκην τινί, give notice of a trial, D.47.42, Plu. Cam.11(Pass.); appoint or summon by public notice, “ἐκκλησίας” Aeschin. 2.60,61; χορηγοὺς π. appoint as choregi, Arist.Oec.1352a1; “π. τινὰ [κληρωθησόμενον̣ τ]ῆς φυλῆς ἣν ἂν βούληται” Supp.Epigr.4.183.15 (Halic., iii B.C.); “π. τοὺς λειτουργήσοντας” IG5(1).1390.73, cf. 74 (Pass., Andania, i B.C.); “στρατιᾶς κατάλογον” Plu.Cam.39; “φρουρᾶς ἡμῖν προγραφείσης” D.54.3; “π. ὅσα δεῖ χρηματίζειν τὴν βουλήν” Arist. Ath.43.3; ἀπὸ τίνος ἄρχοντος καὶ ἐπωνύμου μέχρι τίνων δεῖ στρατεύεσθαι ib.53.7; οἷς κατ᾽ ὀφθαλμοὺς . . Χριστὸς προεγράφη was proclaimed or set forth publicly, Ep.Gal.3.1, cf.

Youngs Lateral Translation has Gal 3:1 has ‘described before among you’ –

“O thoughtless Galatians, who did bewitch you, not to obey the truth — before whose eyes Jesus Christ was described before among you crucified?”

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Galatians+3&version=YLT

It seems like a chicken and egg riddle. Was the excitement and determination to spread the gospel a result of discovering / inferring that the Hebrew scriptures contained the embryo message of a suffering servant Messiah who had ALREADY been crucified at the start of the present age, knowledge of which provides spiritual power to those who accept the message ? Or, was there a real Jesus who had actually then recently lived and who can be discovered to fit PREDICTIONS contained in the Hebrew scriptures ? Given the supernatural events portrayed in the OT & NT which we know today are virtually impossible, I am inclined to the former view that fits with the Jewish people’s desperation to find salvation from Roman oppression and be reconstituted as a nation. I have some good friends who are Jews (Gabor, Jonathan and Peter) and I like them very much. I am not predisposed against Jews. However, what the STATE of Israel has done to the Palestinian people by stealth and deception in the last 80 years, and the false way this has been and continues to be written into history by the mass media (i.e. the origins of the exodus from the nations back to Palestine via the Balfour Declaration in 1917) strengthens my view that things are not what they seem – that the official story of the Bible is propaganda, championed by the STATE of Rome.

Interesting is that Maurice Mergui, independently from Wilcox, reached the same conclusion about the wood of the Isaac’s sacrifice and the tree/cross:

Elévation au bois.

Ruben, on l’a vu, donne un “conseil” à ses frères. Des frères qui, eux-mêmes, se “concertent”. On reconnaît ici une élaboration midrashique sur le mot ‘etsa (conseil, concertation, complot) qui ressemble beaucoup au mot ‘ets (arbre). Dans le Targum sheni sur Esther, les arbres tiennent justement conseil pour savoir sur lequel d’entre eux Haman sera pendu. Cela confirme que le choix de la mort de Jésus, la suspension au bois ou l’élévation au bois (grec stauros, un bois, devenu une crux en latin) est de nature midrashique. Ce choix du bois est en réalité surdeterminé: il provient également de l’épisode du sacrifice d’Isaac. En Gn 22, 3 il est en effet question du ‘atse ‘ola, du bois du sacrifice (ou de l’élévation, ‘ola) ainsi d’ailleurs que de l’agneau du sacrifice (ou de l’élévation, se ha’ola). De la notion de sacrifice on passe aisément (en hébreu, pas en grec) à celle d’élévation https://www.lechampdumidrash.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=177:vendeurjudas&catid=88:lecture-midrashique-des-evangiles&Itemid=486 translation:

Elevation on the tree.

Ruben, as we’ve seen, gives “advice” to his brothers. Brothers who, themselves, “concert” among themselves. We recognize here a midrashic elaboration on the word ‘etsa (advice, consultation, conspiracy) which is very similar to the word ‘ets (tree). In the Targum sheni on Esther, the trees decide about which of them Haman will be hanged on. This confirms that the choice of the death of Jesus, the hanging on the tree or the raising from the wood (Greek stauros, a wood, which has become a crux in Latin) is of a midrashic nature. This choice of wood is in fact overdetermined: it also comes from the episode of the sacrifice of Isaac. In Genesis 22:3 there is in fact reference to the ‘atse ‘ola, the wood of the sacrifice (or of the elevation, ‘ola), as well as to the lamb of the sacrifice (or of the elevation, se ha’ola). From the notion of sacrifice one easily passes from the Hebrew notion (in Hebrew, not in Greek) to that of elevation.

If I understand correctly, Mergui reaches his conclusion on the basis of a Hebrew text behind the gospels. Wilcox’s case arises from the assumption of a Greek text behind Paul and other NT texts (Acts, 1 Peter) — a Greek translation other than the Septuagint. I believe Mergui’s thesis is that Greek translators would attempt to introduce some form of wordplay in Greek if they saw it in their Hebrew source. We need some assurance that we are not diving into circularity of reasoning before going too far down these paths. Some very striking examples may be able to provide that assurance to some extent.

Ok, but it is interesting the Mergui’s view about the midrash in action between the OT story of the Brothers of Jacob who are reluctant to kill him, and the Talmudic story about the trees who are reluctant to be chosen for the hanging of Haman, contra factum that in both cases the victim will die. The only difference is that Haman is evil, while Jacob is righteous. Hence, the connection ‘crucifixion on tree’/expiatory victim was already in the air.

I have to confess that I do not automatically see the phrase “hang on a tree” as referring to crucifixion. I rather see it as a good old-fashioned lynching.

My own inclination would be to say “nailed to” rather than “hang on”, and even when the main participant is fixed to the cross with ropes rather than nails, my own inclination would be to say “tied to”.

But I don’t know whether neck-stretching was an ancient Jewish practice, or whether the various commentators have addressed this point.

Crucifixion was a very common means of execution through the Persian era, the Hellenistic and then Roman era.

According to Samuelsson (“Crucifixion in Antiquity”) we have no records of noose-hanging in the Persian era. Samuelsson further notes that Josephus uses two different words to describe hanging alive from a stake so that one dies slowly on the one hand and a quick death by hanging by the neck on the other.

Cook (“Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World”) tells us that there is no evidence that Romans ever executed criminals by hanging by the neck. Cook also describes what he called a “lynching” in late Roman times — the mob in Alexandria “lynched” their victims by crucifying them.

Of the Dead Sea Scrolls, 4QpNah speaks of “hanging men up alive” and “hang alive upon a tree” — seem to refer to Deut. 21:22-23 but primarily to change the meaning from hanging up a corpse for display to hanging up on the tree in order to have them die. Not much more can be said about that text, according to the Wilcox article.

The Temple Scroll is said to be more specific and pointed towards crucifixion, however. The point is to describe “death by hanging alive” — that sounds more like crucifixion than hanging them as a means of suffocating them by the neck or breaking the neck. It’s for the most serious of crimes so prolonged death seems to fit the context.

Lynching in our culture may bring to mind hanging someone by the neck but implement and crucifixion appear to be more common as means of judicial execution in the Second Temple era.

I have only skimmed the subject, though. It’s not cheerful reading exploring all the minutiae of judicial and extra-judicial methods of killing in the ancient world.

Thanks for that summary.

No need to fear death by water either way.