The Greek Mythicists website has posted a (Greek language) interview with Thomas L. Thompson. The interview page is Συνέντευξη με τον Thomas L. Thompson: Ο Βιβλικός Μινιμαλισμός και ο ιστορικός Ιησούς. The person responsible for the site, Minas Papageorgiou, has kindly sent me an English translation. It is very lengthy so I will only post one part of it for now. More to follow. Thanks to Minas Papageorgiou/Μηνάς Παπαγεωργίου.

The Greek Mythicists website has posted a (Greek language) interview with Thomas L. Thompson. The interview page is Συνέντευξη με τον Thomas L. Thompson: Ο Βιβλικός Μινιμαλισμός και ο ιστορικός Ιησούς. The person responsible for the site, Minas Papageorgiou, has kindly sent me an English translation. It is very lengthy so I will only post one part of it for now. More to follow. Thanks to Minas Papageorgiou/Μηνάς Παπαγεωργίου.

(For background: The Vridar blog is not a “Jesus mythicist” blog even though it is open to a critical discussion of the question of Jesus’ historicity. I do not see secure grounds for believing in the historicity of Jesus but it does not follow that I reject Jesus’ historicity. Clearly, the Jesus of the Gospels and Paul’s letters is a literary and theological construct but it does not follow that there was no “historical Jesus”. Nor do I endorse all views that I have seen associated with Greek Mythicists, though I have been included in one of their publications: see Jesus Mythicism: An Introduction by Minas Papageorgiou and To the Greeks, Vridar in a Greek publication)

Who is Thomas L. Thompson? If you only have the vaguest idea or none at all see my notes at the end of this post. His works have certainly influenced me greatly.

The English language version of the interview, part 1 . . . .

1) Υοu spent a big part of your life in Tübingen, Germany. Would you agree that you were touched by Bruno Bauer‘s aura?

Bauer was much more influential in Berlin and Bonn than Tübingen, where in New Testament studies, Ernst Käsemann drew far more in the direction of establishing and defending an historical Jesus, much in the spirit of the “Jesus Seminar” in the States. In Old Testament studies and Palestinian archaeology, which were my primary interests, the tradition rather lay in comparative literature and comparative religions. Kurt Galling, editor of the great 5 volume, German encyclopedia of religion (Religion in History and the Present 1935) was my professor. He was a student of Hugo Gressmann and Hermann Gunkel and held history and archaeology separate from literature and theology and the study of the Bible was, first of all, a literary work rather than history!

2) In Greece, it is rather impossible to see an academic theologian holding a critical stance towards the Bible. Are things different in the rest of the world?

Greek orthodoxy sees the role of theology as explanatory and Greek theology—much like Roman Catholicism is often very defensive of traditional teaching, except that Greek theology tries to idealize the theology of the early church fathers, while Catholicism looks to the theology of Aquinas and the European Middle Ages as the ideal. But they are both rapidly changing today and one finds a few sound, critical scholars in Greece today and an even greater number of them among Roman Catholic scholars. I think the most influential of conservative scholars are the fundamentalists in the US, where the Bible seems to be read as a description of actual events in which God was the primary active figure. Critical scholarship, which starts from the observation that biblical narrative is first of all literature and needs to be treated as such. It is strongest in Europe, where a strong commitment to critical humanism is the norm for most universities: especially in Germany and Denmark. Perhaps it is best to think of individual scholars and universities rather than countries. The university of Rome, Göttingen, Tübingen, Sheffield and Copenhagen insist that biblical studies be critical rather than traditional.

3) Explain to us in a few words what biblical minimalism is, who the scholars that comprised the core of its existence were and what was your part in this.

Biblical minimalism grows out of the failure of biblical archaeology’s efforts to provide a critical history of Israel. It is important to point out that “minimalism” is a term which was used by opponents of critical biblical scholarship. It was not a self-description. The development in critical biblical studies, which came to reject the use of the Biblical narrative as a historical description of past events was called “minimalism” because these scholars did not share the assumption of, for example, biblical archaeologists, that history could be written by bringing together evidence from biblical narrative and our knowledge of ancient history. Minimalists saw the Bible as allegorical literature and consequently separated their use of archaeology from the Bible to write their history of Palestine. Indeed, understanding history of the South Levant as a regional history of Palestine, rather than as an ethnocentric history of the people of Israel allowed us to understand the Bible’s literary narrative of Israel as a fictional and theological product: what I came to refer to as a “mythic past.” In contrast, our history (of Palestine) is evidence-based in archaeology and contemporary inscriptions rather than biblical narrative, as in biblical archaeology.

Among the earliest scholars committed to a “minimalist” approach to historical questions included such as

I was not aware of all of these names cited. But you can find posts referencing the names

- Van Seters,

- Niels Peter Lemche,

- William Dever, (I thought Dever opposed “minimalists”, certainly he opposed Thompson)

- Israel Finkelstein,

- Keith Whitelam,

- Philip Davies,

- Ingrid Hjelm,

- Emanuel Phoh,

- Lukasz Niesolowski,

- Lester Grabbe

in Vridar.

Bernd Diebner, Giovanni Garbini and John Van Seters, in the 1960s,

followed by Niels Peter Lemche, William Dever and myself in the 1970s

and Israel Finkelstein, Robert Coote, Keith Whitelam, Philip Davies, Gösta Ahlström and Axel Knauf in the 1980s

and 1990s and Ingrid Hjelm, Emanuel Pfoh, Lukasz Niesiolowski, Lester Grabbe, Issa Sarie, Joshua Sabih, Hamdan Taha and many others in the new millennium.

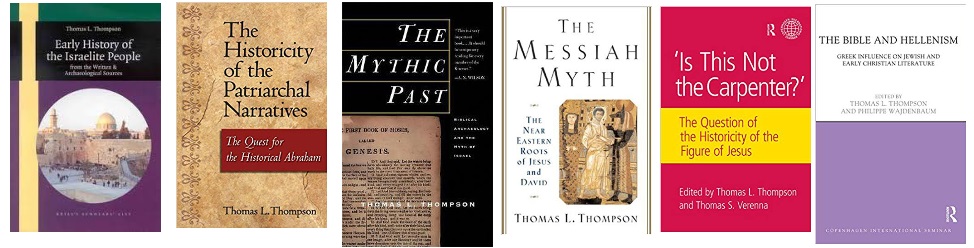

There are many others I could mention. I believe that, today, a considerable majority of critical scholars employ minimalist principles in regard to writing a regional history of Palestine. There are many facets to this thorough-going change in biblical scholarship and minimalism cannot be adequately understood if one only refers to the three or four scholars who were most self-consciously engaged in such changes. Although no shortlist of works can hardly adequately reflect the many changes, which have been most commonly cited does, illustrate minimalism’s complexity. Among some the most influential book-length monographs and collections of essays in minimalism have been my own 1974 Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives works, Van Seters’ 1975 work, Abraham in History and Tradition, John Hayes and J. Maxwell Miller’s Israelite and Judean History of 1977, Lemche’s Early Israel of 1985; R. Coote and Keith Whitelam’s The Emergence of Early Israel of 1987, Finkelstein’s The Archaeology of Israelite Settlement and Garbini’s History and Ideology in Ancient Israel from 1988, Lemche’s The Canaanites and Their Land of 1991, Davies In Search of ancient Israel and my Early History of the Israelite People of 1992, Keith Whitelam’s The Invention of Ancient Israel of 1996 and Ingrid Hjelm’s Jerusalem’s Rise to Sovereignty from 2004.

4) Could you describe to us the consensus about the biblical reliability when you began promoting the theory of biblical minimalism? What were the reactions you faced from your colleagues and how did your arguments finally manage to gain ground?

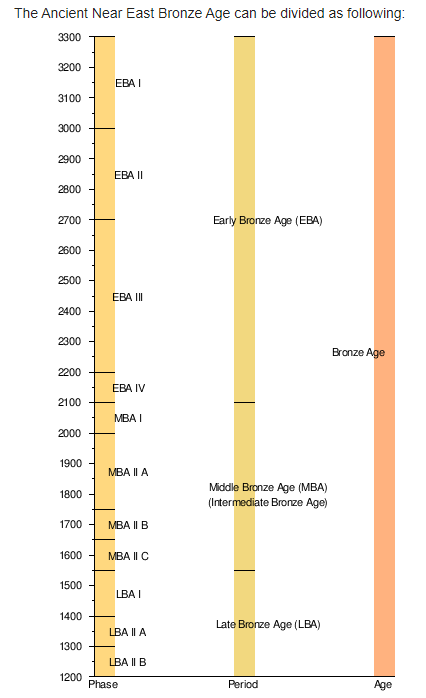

Minimalism began as a reaction to the historicism of biblical archaeology, which understood the biblical narrative as a history of Israel and the establishment of such a history through a historicizing of biblical narrative. Indeed some biblical archaeologists, such as George Ernest Wright, understood the “acts of God” as biblical archaeology’s essential data and evidenced-based foundation for this historiography! For Wright and many of his students, theology was rooted in the events of the past and, by and large, biblical narratives were understood as historical. In particular, the stories of the patriarchs were presented by the vast majority of scholars, as a narrative, which had been clearly proven to be historical, established already in the early transition period of EB IV-MB I (ca. 2000 BCE). The entire history of Israel was accepted as historical from the patriarchs through the Books of the Maccabees.

In reaction to this, minimalism separated the biblical perspective of the past from an archaeological-based history, in which archaeology was interpreted independently of the perspectives of biblical literature. The immediate reaction to the first minimalist works of the 1960s and 1970s, which, for the most part, concentrated on the stories from Genesis to Judges, was uncompromisingly harsh. The two major minimalist works involved, my 1974 Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives and John Van Seters 1975 book: Abraham in History and Tradition, though understood generally as convincing and thorough in their argument and presentation, resulted in a bitter debate which lasted nearly ten years, a period in which I was not only academically unemployed but also unemployable in the United States from 1976 to 1984. I could not find a publisher for my dissertation in the United States and both Van Seters and I were repeatedly attacked by leading scholars at meetings of the American Society or Oriental Research, the Catholic Biblical Association and the Society of Biblical Literature.

However, in 1985, I was appointed as annual guest professor for a semester at the École Biblique in Jerusalem. By this time Van Seters and my understanding of the patriarchal narratives was fully accepted. In the aftermath of the early minimalism of the 1960s and 1970s, a consensus was reached in the early 1980s about the essentially folkloric and fictional character of biblical narrative from the beginning of Genesis to the closure of the book of Judges. History, one could say, began with the United Monarchy.

In 1991 and 1992, however, the publication of new works by Lemche, Davies and me, concluding in a rejection of the historicity of the biblical narratives about the United Monarchy and the Book of Kings. A new wave of protests from American and Israeli scholars began, even more virulent than that of the 1970s. Charges of incompetence, anti-Semitism, lack of scholarly integrity and willful distortion became the norm for this criticism. These reached their most extreme perhaps with the publication of a book in 2001 by William Dever, What Did Biblical Writers Know?, which made such personal attacks on me more than 200 times! From the Catholic side, having taught for 3 years at Marquette University in Wisconsin, I was just coming up for tenure when my Early History of 1992 was first published. This resulted in a denial of tenure at the university. In a more positive response to its publication, however, I was invited to take Edward Nielsen’s chair in Old Testament studies at the University of Copenhagen and I was able to return to friendly Europe.

The growing split in Old Testament scholarship continued to spread through the 1990s and the early 2000s, though a return to civility in Europe and elsewhere, apart from in Israeli and American scholarship since then has reflected a marked acceptance of the scholarship and principles fostered by minimalism’s separation between an expansive understanding of the Bible as primarily a literary work and the understanding of Palestine’s history as evidence and rooted in paleography and archaeology.

5) Should we consider biblical figures like Moses and Abraham as historical persons? What is the reliability of various incidents, battles and miraculous events that are being described in the Bible?

Narrative expansions of genealogies and other folkloric origin stories in the Bible from the genealogy Shem (= Asia), Ham (= Africa) and Japheth (= Europe) in Genesis 10 to the story of Solomon in 1 Kings are not historiographical narratives. They form rather folkloric chain narratives. The structure of the ethnographic story of Abraham creates the patriarch of Syria, Palestine and the southern steppe and desert regions. He is their common ancestor, fictively uniting Arabs, Sabeans and Midianites, Arameans and Phoenicians (including Israelites and Judeans). The themes of this chain narrative build their narrative as illustrative of a return from exile under the protection of the just god Yahweh.

The “events” of the stories of Genesis through Judges are all fictive, imitative and comparable to the stories of Homer in both the Iliad and Odysseus. The central plot of the biblical narrative, beginning in Genesis, is probably inspired by Plato’s understanding of an ideal and just society. The stories of 1-2 Samuel and 1-2 Kings, however, use regnal lists, with the names and chronologies for the reigns of kings in the otherwise unrelated patronage kingdoms of Judah and Israel to sketch a narrative of Yahweh’s coming to understand his role of patron God, who must learn to become a god of mercy and compassion. It is primarily a philosophical story, very similar to the story of Job, which uses the figure of Job to illustrate Israel’s gradual enlightenment. However, in Samuel-Kings it is Yahweh who is the subject of enlightenment, learning how to become merciful and compassionate.

6) In your book The Messiah Myth, 2005, you claimed that the basis for the David and Jesus traditions comes from earlier Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman texts. Could you tell us a few words about that?

My interests in history writing were not limited to my expanding archaeological interests, which followed the seven years I worked on Bronze Age settlement patterns for the Tübingen Atlas of the Near East (1969-1976). I also had interests in intellectual history, which engaged me especially with Old Testament narrative literature and the manner in which such an intellectual perspective was engaged. When I start out to write my Messiah Myth of 2005, I was involved in two fascinating tropes, which were frequently reiterated in both Old Testament and ancient Near Eastern narratives. The first of these was engaged by royal inscriptions with a short first-person narrative of how the king as a young man began his career in hardship and was sent into exile in a drought-plagued region (usually in Palestine) by his patron. In his wilderness, the future king was treated with favor and rose to prominence. He fought a duel against a great warrior and at times a giant or dragon, whom he killed with a single and usually unexpectedly successful shot! He became rich with a band of soldiers at his command, was reconciled with his patron and finally invited to return and take up his throne. There are more than twenty such stories found on inscriptions from the ancient Near East. The story is also used in the story of David’s rise to power and the Old Testament’s mythic concepts of the Messiah of apocalyptic literature and is, for example, used metaphorically in the book of Job.

The second trope I was interested in were the hundreds of examples of what I came to refer to as The Poor Song which praised the care of the widow and the orphan, one who had no home, the poor and the needy and a myriad of variations. This trope is most notable in the Book of Isaiah in biblical literature but is also found on inscriptions, in Qumran’s literature, Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts. In the story of the king’s rise to power, it is often used to mark his goodness as a just king and in Messianic literature it is endemic. When I wrote The Messiah Myth, I set out particularly to show that biblical narratives, especially on the one hand the narratives of 1-2 Samuel and 1-2 Kings used both the Poor Man’s Song and the story of the king’s rise to power to construct their narrative, which, through allegory, was one of the primary, theologically motivated goals of some of the pivotal roles of the narrative. These tropes are found most emphatically in the long story of the miracle workers and prophets, Elijah and Elisha, which dominates the supposedly historical 1-2 Kings, a story in which iron floats on water! The question of this book was not about the historicity of Jesus so much as about how the stories worked as literature and were not historiographic. The Jesus of the gospel is not historical, because it is not about Jesus. It is about suffering and the poor and it is about Yahweh’s need of compassion for his widowed people! For myself, this was fulfilling what had been a long-standing interest since 1968. It is an argument for the use of comparative literature as one of the essential methods for defining the literary character of the folkloric and mythical biblical narratives.

7) For that book you received criticism from Prof. Bart Ehrman, who often attacks those who doubt Jesus’s historicity. What were his arguments and what was your rebuttal? You also participated in the “Is this not the carpenter’s son” for that reason… What is your opinion on Jesus’s historicity?

Bart Ehrman has a very poor understanding of my book. What he criticized most emphatically was not in my book. He took the book as being a study or review of whether Jesus was historical, even though I explicitly argued that I was talking about the lack of historicity and rather literary character of the gospels and their dependence on Old Testament and ancient Near Eastern tropes. These tropes are not historical and one cannot find an historical Jesus there. To argue for an historical Jesus you need something more than these stories. I do not deny that Jesus existed. I wouldn’t know! That is what I wrote.

Most irritating of his criticism is his claim that I was not qualified for writing such a book. Who is more qualified than an Old Testament scholar interested in comparative literature. I was writing about Old Testament tropes in the gospels and am perfectly qualified to do that. Can he read the gospels as anything other than a commentary on the Jewish Bible? My 1974 Historicity and my 1992 Early History are about the question of historicity and my 1987 Origin Tradition is about the structure of Old Testament narratives, which are frequently reiterated in the gospels. The tropes that I had long since identified as The Poor Man’s Song and that of the Testimony of the Just King are specifically related to my earlier studies of these tropes. Who would be a better fit to discuss them?

I don’t think it is possible without considerably different evidence than we have to judge whether Jesus was historical. However, if the gospels were judged to be unhistorical and unable to support historicity one has problems. Who is this Jesus (Joshua/ the savior) if not the Jesus of the gospels and if Jesus in not historical, where would we go for evidence. In the Book Is this Not the Carpenter’s Son? the essays collected largely judge the issue unresolved.

Continuing . . . .

Who is Thomas L. Thompson?

All Vridar posts tagged under Thomas L. Thompson are archived here.

For those catching up, there is a Wikipedia page. I have posted several times on books by Thomas L. Thompson that I have read. They have certainly been most influential on my views and approach to the “Old Testament”. Following his methods, I have also found myself raising new questions and perspectives concerning the Gospels and Acts. Thompson led me to read the Jewish Scriptures first and foremost as literature and to interpret the finds of archaeology as sources to be interpreted independently of the biblical narrative. All posts to which I have tagged Thomas L. Thompson’s name are archived here. Books and articles by Thomas L. Thompson that have kept in my personal library (with books in bold type) are

Thompson, Thomas L. 1987. The Origin Tradition of Ancient Israel: I. The Literary Formation of Genesis and Exodus 1-23. Sheffield: Sheffield.

———. 1994. Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. Brill.

———. 1995. “‘House of David’: An Eponymic Referent to Yahweh as Godfather.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 9 (1): 59–74.

———. 1999a. The Mythic Past: Biblical Archaeology and the Myth of Israel. New York: Basic Books.

———. 1999b. “Historiography in the Pentateuch: Twenty‐five Years after Historicity.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 13 (2): 258–83.———. 2002. Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives. Harrisburg, Pa: Trinity Press International.

———. 2000. “Lester Grabbe and Historiography: An <i>Apologia</I>.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 14 (1): 140–61.

———. 2001a. “On Reading the Bible for History: A Response to William G Dever.” Journal of Biblical Studies

———. 2001b. “The Messiah Epithet in the Hebrew Bible.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 15 (1): 57–82.

———. 2004. Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition. London ; New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

———. 2005a. “The Role of Faith in Historical Research.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 19 (1): 111–34.

———. 2005b. The Messiah Myth: The Near Eastern Roots of Jesus and David. New York: Basic Books.

———. 2007. “Mesha and Questions of Historicity.” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 21 (2): 241–60.Thompson, Thomas L., and Philippe

Wajdenbaum, eds. 2014. The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Routledge.

Thompson, Thomas L., and Tom Verenna, eds. 2011. “Is This Not the Carpenter?”: The Question of the Historicity of the Figure of Jesus. London ; Oakville, CT: Equinox.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Wow! How did you pull this off Neil. Wonderful! Dr. Thompson was one of my Hebrew Scriptures professors at Marquette Univ. and became a close friend and significant supporter through my Ph.D program. Many of my fellow Ph.D classmates who were fundamentalist and evangelical in nature had a hard time with him about his views but I think they should have been more open to his methodological issues and not looking to do apologetics… and they perhaps didn’t see the incredible value in his work….

Due to my work there under him and my effort to explore the areas of history and method.. I had had it up to my ears with NT apologetics and other things theological. And I ended up as a research and teaching assistant/fellow , not to Dr. Thompson himself but under another creative and incredible OT scholar..Dr. Sharon Pace Jeannsone at the time. I also had the support of Dr. Father Joseph Leinhardt.

Dr. Thompson (Tom!) Thank you for all you have meant to me, even though our contacts have been few over these many years. And by the way that pic of you makes you! Wow! Hope to connect with you soon in more depth.

And thanks Neil for putting this up.

Hi Martin, It wasn’t me who pulled it off. It was Minas. I just did a copy and paste with minimal editing.

Thanks Neil for the note. Hope all is well. Fascinating interviews. Really interesting and I have always loved the way he puts things.

Just an extra note too.

I also became friends with one of Dr. Thompson’s brilliant students. Dr. Tom Bolin. High Tom!

Really enjoyed your friendship back then and your work on Jonah! Everyone needs to check it out.

Sorry I haven’t kept up contact over the years….lots going on for many of us who are serious about history and biblical studies and related aspects and some health related issues.

Cheers

Marty

Dear Martin,

It is so good to hear from you. My e-mail address is tlt[AT]teol.ku.dk. Please write and let me know how you are doing!

Tom