Continuing a discussion of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. . . . All Litwa review posts are archived here.

Continuing a discussion of M. David Litwa’s How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. . . . All Litwa review posts are archived here.

This post covers chapters 7 and 8, “Magi and the Star” and “Child in Danger, Child of Wonder”. Even though I often disagree with Litwa’s interpretations and conclusions I do find the information he presents and questions raised to be very interesting and informative.

Litwa’s theme is that even though the authors of the canonical gospels composed narratives that to moderns are clearly mythical, by ancient standards of historiography such “mythical” episodes were part and parcel of “what happened”. Similar fabulous happenings are found in serious works by ancient historians, Litwa claims. Such types of events belonged to the “thought world” of that broad culture throughout the Mediterranean and Levant.

[I agree: ancient historical works do contain “mythical” elements but I have certain reservations about authorial intent and gullibility since, in my reading, they generally found ways to distance themselves from any suggestion that they were committed to the veracity of those sorts of stories.]

Ancient authors meant for readers to understand them as part of history, not myth, Litwa insists: the stories were indeed fabricated but their presentation was in the form of historical narrative. Ancient readers would have accepted them as historical — which is exactly what the authors intended.

So in the case of the virgin birth, Litwa points out that ancient Persians, in their Zoroastrian beliefs, had a similar myth about a future saviour figure. The Magi are Persian figures, so it is interesting that in Matthew we find a story of a virgin birth of a saviour with magi present. No, Litwa is not saying one story directly derived from the other and he notes significant differences between them. That is Litwa’s point, recall. These sorts of stories were part of the cultural backdrop in the world that produced our gospels.

Litwa refers to Mary Boyce’s study and for interest’s sake I will copy a relevant section from one of her books:

The original legend appears to have been that eventually, at the end of “limited time”, a son will be born of the seed of the prophet, which is preserved miraculously in a lake (named in the Avesta Lake Kąsaoya), where it is watched over by 99,999 fravašis of the just. When Frašō.kǝrǝti is near, a virgin will bathe in this lake and become with child by the prophet, giving birth to a son, Astvat.ǝrǝti, “he who embodies righteousness”. Astvat.ǝrǝti will be the Saošyant, the Saviour who will bring about Frašō.kǝrǝti, smiting “daēvas and men”; and his name derives from Zoroaster’s words in Y. 43.16: astvat ašǝm hyāt “may righteousness be embodied”. The legend of this great Messianic figure, the cosmic saviour, appears to stem from Zoroaster’s teaching about the one “greater than good” to come after him (Y. 43-3)21, upon which there worked the profound Iranian respect for lineage, so that the future Saviour had necessarily to be of the prophet’s own blood. This had the consequence that, despite the story of the Saošyant’s miraculous conception, there was no divinisation of him, and no betrayal therefore of Zoroaster’s teachings about the part which humanity has to play in the salvation of the world. The Saviour will be a man, born of human parents. “Zoroastrianism … attributes to man a distinguished part in the great cosmic struggle. It is above all a soteriological part, because it is man who has to win the battle and eliminate evil”.

(Boyce, 282)

Magi and births of future kings

The Greek historian Herodotus tells a tale of Magi interpreting a dream to mean a future king has been born:

Astyages had a daughter called Mandane, and he dreamed one night that she made water in such enormous quantities that it filled his city and swamped the whole of Asia. He told his dream to the Magi, whose business it was to interpret such things, and was much alarmed by what they said it meant. Consequently when Mandane was old enough to marry, he did not give her to some Mede of suitable rank, but was induced by his fear of the dream’s significance to marry her to a Persian named Cambyses, a man he knew to be of good family and quiet habits – though he considered him much below a Mede even of middle rank.

Before Mandane and Cambyses had been married a year, Astyages had another dream. This time it was that a vine grew from his daughter’s private parts and spread over Asia. As before, he told the interpreters about this dream, and then sent for his daughter, who was now pregnant. When she arrived, he kept her under strict watch, intending to make away with her child; for the fact was that the Magi had interpreted the dream to mean that his daughter’s son would usurp his throne.

(Herodotus, 1.108)

With this second dream the king is fearful enough to order the murder of the infant. The infant survives, however, and when the king learns his order has been defied he brings the magi in again for consultation. The king accordingly slew the innocent child of the servant who had disobeyed him.

Litwa identifies similar structures in the accounts of Herodotus and the Gospel of Mattew concerning

- magi who inform a king that a child is born who will replace him,

- the king ordering the child to be killed,

- the child “miraculously” escaping,

- and the king subsequently killing an innocent.

What interests Litwa, though, is that both “accounts are presented as historiography” (p. 107). Herod was known to be cruel, so even though there is no evidence that he did order the massacre of infants in Bethlehem, the tale in Matthew’s gospel “sounded enough like historiography to be accepted as true” (p. 107)

That sounds reasonable enough on its own, but what are we to make of the fact that Pilate was also known for his cruelty but all the evangelists, Matthew included, present him — most UNhistorically — as benign and soft when he meets Jesus and is cowered by the Jewish priests and mob into doing their will against his own will? Yet that story has also been accepted as true: despite what was known of Pilate’s character, it also “sounded enough like historiography”.

Litwa addresses other ancient tales involving magi (Plutarch, Quintus Curtius, in relation to Alexander the Great), informing us that those tales, too, are implausible to moderns (no persons can predict the future of an individual from dreams), so if the story of the magi in the Gospel of Matthew is likewise implausible, no matter, since that’s what the historical narratives of ancient historians looked like. There certainly are many accounts of dream interpretation in various historical works but they are “add-ons” and the overall narratives of historians are not one series of miraculous events after another, as we find in the gospels.

Magical guiding stars

Litwa finds ancient stories of guiding stars to be more useful explanations for the star of Bethlehem that led the magi to Jesus than the various extant attempts to identify astronomical observations of that period. Again, Litwa is not arguing for direct “mimesis” but a more general influence of stories and concepts that were “in the air” throughout the Mediterranean cultural world.

We read of ancient sources that speak of magi interpreting dreams of astral bodies in ways that spoke of rulership; of the historian Pompeius Trogus writing of an unusual star appearing at the birth of Mithridates, the king of Pontus who would challenge Rome, and again at his ascension to the throne. What I found of most interest in Litwa’s discussion is not his thoughts on “long-haired stars” or comets but his references to stars that were said to point to very specific places on earth — as per the star being said to stand over the house where the infant Jesus was to be found.

- A sword-shaped star hung over Jerusalem just prior to its fall to the Romans (Josephus)

- The Torch of Timoleon, a fiery “star” that led the fleet the Corinthian general Timoleon before falling down to mark the exact part of Italy to be beached (Plutarch)

- The scholar Varro interpreted Virgil’s poetic account of the goddess Venus guiding Aeneas to Italy as Aeneas being led by the planet Venus (Servius)

(Source-author links are to the relevant passages describing the events.)

Many ancient people believed in omens and yes, they found their way into “history” books. Omens were even more integral to mythical stories and other forms of fiction. That point raises questions about the strength of Litwa’s attempt to explain why the gospels were believed to be historical by certain readers but not all.

Chapter 8

Jesus is part of a crowd of famous infants in danger

Litwa sums up some of the reasons many scholars question the historical truth of the account of the newborn Jesus being carried to Egypt to save his life from a tyrant set on killing him, only to return after that king’s demise to his homeland. The basic idea of the story comes from “the mythic history of Israel”: Joseph, followed by his brothers, entered Egypt as an alternative to dying in Canaan and their Israelite descendants left Egypt as God’s “son” (Hos. 11:1). Dale Allison (The New Moses, 140 ff) adds that there are clear textual pointers to Matthew’s account being basic specifically on the biblical story of Moses though for some reason Litwa makes the Moses comparison only with Josephus, not the biblical texts.

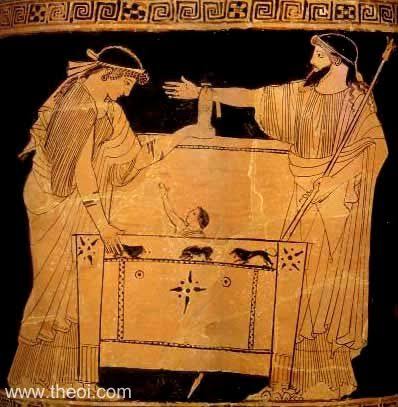

Perseus

A comparable story is the myth of Perseus, a hero who was placed in a box and cast into the waters for his own “protection” from a wrathful king, Acrisius. Acrisius is determined to kill the child whose father is none other than the god Zeus himself!

Augustus

Compare, further, the story of the historical Augustus, first emperor of Rome. The historian informs readers that before his birth a strange portent of some kind was interpreted as a prediction that a future king of Rome had been born. Since by this time the Romans had long since driven out their kings and vowed never again to be ruled by one, the Senate decreed that no newborn male child was to be allowed to live for that entire year. Here is how Suetonius tells the tale:

Julius Marathus records that a few months before Augustus was born a prodigy was generally observed at Rome, which announced that nature was bringing forth a king for the Roman people. The senate, he continues, was most alarmed and agreed that no child born in that year should be raised. However, those whose wives were pregnant ensured that the decree was not registered in the treasury, since each hoped that the prodigy referred to his own child. I read in the books of Asclepiades of Mendes, entitled ‘Theologoumena’, that Atia, attending the sacred rites of Apollo in the middle of the night, had her litter positioned in the temple and fell asleep, while the other matrons were also sleeping. All of a sudden, a serpent slid up to her, then quickly went away. On waking, she purified herself, as she would after sleeping with her husband. And at once there appeared on her body a mark in the image of a snake and she was never able to get rid of it, so that ever afterwards she avoided going to the public baths. Augustus was born ten months later and for this reason is believed to be the son of Apollo.

(Suetonius, Deified Augustus, 94)

Concerning the ten months, there is a 1987 article the Bulletin of the History of Medicine that states: “The reckoning of months of pregnancy was usually inclusive in Greco-Roman antiquity; thus, our “nine months’ child,” a pregnancy of term, was most often referred to as a “ten months’ child” by ancient writers.” (Hanson, p. 589)

Litwa comments:

Julius Marathus (and Suetonius) told this story with the apparent intention that it be understood as describing real events. There is nothing in it that is strictly speaking impossible from a modern point of view. Even if one detects some obvious propaganda for the Julian family, the ancient reader would have classified this story as a historical report. (p. 118)

True. But keep in mind that Suetonius even broke his own rules when it came to writing about Augustus.

Romulus and Remus

Many of us have heard the story. For a refresher of the myth of how they were fathered by the god Mars, and how the king, Amulius, sought to kill them to protect his throne, of how they were hidden in a basket placed in a river and eventually raised by a she-wolf, see the Wikipedia article.

Moses

For Josephus’s elaborations on the biblical story of Moses’ birth see Antiquities, Book 2, 210-232. Litwa outlines this version, noting that

Despite the dissimilarity, basic structural parallels recur in the stories of Moses and Jesus. There is a prophecy about a royal child, a wicked king, priestly (and prophetic) personnel, an attempt to kill the child (sometimes involving the deaths of other children), a father’s prophetic dream (only in Josephus and Matthew), a divinely engineered escape, and the child’s return to fulfill prophecy. (p. 120)

It is not part of Litwa’s discussion but it is interesting to try to learn the origins of Josephus’s elaborations. Here the Josephan scholar, Louis Feldman, is helpful. Interestingly, Feldman is less coy than Litwa in suggesting that Josephus borrowed directly from the non-Jewish myths. See the side-box with Feldman’s footnote #28.

28 On Josephus’ knowledge of Greek literature, see my Josephus and Modern Scholarship (Berlin, 1984), pp. 392-419, 819-822, and 935-937. On his knowledge of Latin literature, see Thackeray, Josephus, pp. 119-120; Benjamin Nadel, “Josephus Flavius and the Terminology of Roman Political Invective” [Polish], Eos 56 (1966): 256-272; and David Daube, “Three Legal Notes on Josephus after His Surrender,” Law Quarterly Review 93 (London, 1977): 191-194.

29 As to whether Josephus might have been acquainted with traditions which are found in later rabbinic literature, we may note that Josephus himself remarks on his excellent education (Life, 8-9), presumably in the legal and aggadic traditions of Judaism . . . . [There follows a discussion of the evidence that many of the rabbinic details were known long before they were set down in the rabbinic literature.]

(Feldman, p. 295 f)

There are many parallels to the predictions and wondrous events attending the birth of both the mythological and the historical hero, including the motifs of the prediction of his greatness, of his abandonment by his mother, and of his overcoming the ruler of the land. Josephus’ additions may best be appreciated when his account is compared with parallels in classical literature,28 both mythological and historical, which were undoubtedly well known to many of Josephus’ literate readers, as well as with rabbinic midrashim29 and Samaritan tradition.

As to mythological parallels, one is reminded of the story, so central in Aeschylus’ Prometheus trilogy, of the threatened overthrow of Zeus, since Thetis, whom he is courting, is destined to have a son more powerful than the father. Again, one thinks of the oracle that had declared that Danae, the daughter of Acrisius, the king of Argos, would give birth to a son [i.e. Perseus] who would kill his grandfather, and of the vain attempt of Acrisius to keep his daughter shut up in a subterranean chamber (or tower). One thinks furthermore of Oedipus, whose father Laius had been warned by an oracle that if he begat a son he would be slain by him. Here, too, the infant was exposed but was saved and eventually did slay his father. Other such parallels in Greek mythology may be cited: Achilles, Paris, Telephus, and Heracles.

From Roman mythology or history the births of Romulus and Remus may be cited; in their case King Amulius of Alba Longa not only forcibly deprived his older brother Numitor of the throne that was rightfully his, but also plotted to prevent Numitor’s de- scendants from seeking revenge by making Numitor’s daughter, Rhea Silvia, a Vestal virgin, thus precluding her from marrying; but this plot was foiled when she became the mother, by the war god Mars, of twins, who, though thrown into the Tiber River (thus paralleling Pharaoh’s orders that male children be drowned), were washed ashore, were suckled by a she-wolf, were then brought up by the royal herdsman Faustulus, and eventually overthrew Amulius and restored Numitor to the throne.

As to parallels in classical literature, we find a similar annunciation from the Pythian priestess at Delphi to the father of Pythagoras that there would be born to him a son of extraordinary beauty and wisdom (lamblichus 5.7). Again, there is a legend in connection with Plato (Diogenes Laertius 3.2) of the child who would overcome a ruler. Likewise, as Hadas has pointed out, the apocalyptic technique is seen in Dido’s prediction (Virgil, Aeneid 4.625) of the birth of one who would avenge her being jilted, namely Hannibal.

There are similar historical parallels that were conceivably well known to Josephus and his readers. Thus Herodotus (1.107), one of Josephus’ favorite authors, tells of the dream of Astyages, king of the Medes, that his daughter Mandane would have a son who would conquer Asia. When the son, Cyrus, was born, Astyages, like Pharaoh, ordered that he be killed; but a herdsman saved him and reared him. The son ultimately became king of Persia and defeated Astyages in battle. Moses would thus be equated with Cyrus, the great national hero of the Persians.

(Feldman, 295-297)

In the context of Litwa’s theme Feldman’s following comment is of interest:

Josephus, realizing that his readers would be aware of the many cases in mythology and history where the fates could not be thwarted, could editorialize (2.222):

“Then once again [presumably in addition to the cases of Perseus, Oedipus, Romulus, Cyrus, and all the other instances cited above] did God plainly show that human intelligence is worth nothing, but that all that he wills to accomplish reaches its perfect end, and that they who, to save themselves, condemn others to destruction utterly fail, whatever diligence they may employ, while those are saved by a miracle and attain success almost from the very jaws of disaster who hazard all by divine decree.“

Feldman further points out that Josephus toned down certain miraculous flourishes that we find in other Jewish writings that subsequently appear in the rabbinic tradition because that tradition

seemed much too exaggerated for credibility. . . . (Feldman, 302)

Litwa finds “strong verbal overlaps” (p. 121) between Matthew’s story of Jesus’ flight and Jeroboam’s escape to Egypt (1 Kings 11:40). The point is that such tropes could reappear in literature without denying a sense of “historical plausibility”. Even fantastical elements appeared in Greco-Roman works of history. Again, Litwa downplays the way ancient historians would frequently distance themselves from personal conviction that such tales were necessarily true (presenting them as “what was believed or told”, etc.) and the frequent records we have of ancient persons simply disbelieving such things. His point is half right, at best, I think.

Child geniuses

We know the story in the Gospel of Luke where Jesus, while only twelve years of age, astonishes the learned men in the Temple with his questions and answers (Luke 2:46-47).

We know the story in the Gospel of Luke where Jesus, while only twelve years of age, astonishes the learned men in the Temple with his questions and answers (Luke 2:46-47).

Here, too, Litwa finds a widespread cultural trope.

Cyrus

There is a problem with Litwa’s reliance upon the historian Xenophon for the description of a comparable scenario with Cyrus, however. As Litwa puts it:

Thus we have Cyrus at the same age as Jesus, admonishing his elders, asking them questions, and responding to theirs. He is not arrogant but humble; and his show of curiosity veils a great intelligence within. The author of Cyrus’s childhood saga is no poet or playwright but the famous Creek historian Xenophon (about 430-354 BCE).16

16. Yet as Cicero observed, Xenophon’s portrait of Cyrus was beneficial not because it was written according to historical truth but because it show’s the image of a just ruler (Cyrus ille a Xenophonte non ad historiae fidem scriptus est, sed ad effgiem iusti impeeu) (Letters to His Brother Quintus I.1.23). See further Tomas Hagjg, The Art of Biography in Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 51-66.

(pp. 123, 247)

The endnote #16 pulls the rug from Litwa’s stance. If we turn to Cicero’s passage we find he does not say the portrait of a precocious Cyrus “was beneficial not because it was written according to historical truth”, but something almost the opposite, at least according to the J.S. Watson translation:

The “Cyrus” of Xenophon is written not in accordance with the truth of history, but to exhibit a representation of a just government . . . .

It appears that Cicero did not read Xenophon’s account of the child prodigy Cyrus as history at all. He read it as a philosophical treatise with Cyrus as a prop to illustrate the nature of an ideal form of government. Anyone who reads just a little of Xenophon’s Education of Cyrus will quickly see that the work is indeed a philosophical treatise and not written as either history or biography. But if you don’t trust your own reading here is the judgment of Emeritus Professor of Classics at the University of Bergen (2012), Tomas Hägg:

Whatever generic label one chooses to give it – historical (or biographical or philosophical) novel, romanticized (or fictionalized) biography, mirror of princes – it is clear, right from its introduction, that its main topic is leadership and government, not the life of the historical King Cyrus the Great of Persia (died 530 BC). . . .

Much of the text of the Cyropaedia is devoted to description and discussion of military strategy, political ideology, Persian (or pseudo-Persian) customs and attitudes, and so on, formally more or less attached to Cyrus (sometimes as direct speech), but with little bearing on him as a character or (pseudo-)historical agent. . . .

Xenophon’s approach is clearly not that of a modern biographer intent on development of character, nor that of an ancient historian (like himself in the Hellenica)structuring the narrative annalistically. It is the typical and the general that occupy him throughout, and Bodil Due demonstrates how he develops a special technique of letting a particular scene turn into a general, and vice versa. He is the pedagogue who in this way imprints his ideological message on the reader’s mind, using the figure of Cyrus to actualize theory. . . .

As mentioned, the place in the narrative where Cyrus’ first eleven or twelve years might have been described is instead occupied by a rather detailed description of the Persian educational system, age class after age class (1.2.2-16), without any mention of Cyrus even as an illustrative example. This generalized account, cast in the present tense, is preceded by just a brief mention of Cyrus’ doubly royal parentage and an equally summary statement about his nature: ‘Cyrus is still described in word and song by the barbarians as most handsome (kallistos) in appearance and most humane (philanthmpotatos) of heart, most eager to learn (philomathestatos), and most ambitious {philotimotatos), so that he endured every labour and faced every risk for the sake of praise’ (1.2.1). . . .

(Hägg, pp. 51, 52, 53, 55f.)

The character of Cyrus is evidently idealistic, nothing but a demonstration of the ideal virtues Xenophon is extolling. Xenophon weaves his knowledge of Plato’s account of Socrates’ death into a new creation:

The character of Cyrus is evidently idealistic, nothing but a demonstration of the ideal virtues Xenophon is extolling. Xenophon weaves his knowledge of Plato’s account of Socrates’ death into a new creation:

The references to Socrates’ last minutes in the Phaedo are evident: the part of the body from which life begins to ebb no doubt alludes to feet and legs as specified by Plato (117e), and Cyrus covering himself echoes Socrates covering and uncovering his face (118a). Cyrus, however, asks to be spared the humiliation suffered by Socrates, to have his face uncovered to check that he is really dead. Nor has this death scene singled out anyone, family member or friend, whom we would naturally expect to play Crito, closing his mouth and eyes. The scene is monologic to the end.

Xenophon’s account of Cyrus’ death is an apt point of departure for a few concluding remarks about fact and fiction in the Cyropaedia. Herodotus had let Cyrus die a violent death on the battlefield (1.214.3- 5). Ctesias, in his Persica, also had him fatally wounded in battle, but left him time, before he died, to arrange for his succession and admonish his family. Xenophon, in contrast, has chosen to grant his hero a peaceful death at a ‘very old’ age. Whatever sources he may have had in addition, this is clearly an ideological choice. He is anxious to have Cyrus looking back at a successfully completed life-work, and have him preach about happiness, concord, and immortality. Cyrus is now the wise king, no more the conqueror, and can leave this world content with years and achievements. This free attitude to history is typical of the whole work. The family members and friends we met at the beginning of the story are partly historical figures, partly the author’s own invention. And those who are historical have shifted character and function. Xenophon has avoided the scenario of cruelty, rivalry, and revenge that filled earlier accounts, and instead created an harmonious extended family, with young Cyrus as the beloved prince moving between Persian puritanism and Median liberty, assimilating and storing for the future the best of both cultures – as Xenophon himself had participated in both Athenian and Spartan society.

How, then, are we to explain the constant deviations from known history? Perhaps, as Philip Städter suggests in a penetrating discussion of Xenophon’s ‘fictional narrative’, the question is wrongly put. Xenophon simply did not set out to write historiography this time: ‘Xenophons idealization is essentially utopian, like Plato’s Republic. It describes not what has been, but what ought to be.’ Unlike Plato, he chose narrative as his medium, because it is didactically superior to any abstract discussion. Moreover, Cyrus the Great was a stock ingredient in contemporary Greek discussion; so Xenophon used an historical figure who already had an established reputation as an empire-builder, but filled the character with his own ideals of leadership in war and peace. He may have expected that his historiographical reputation and style would make his “readers” accept Cyrus and his world as historical realities, at least long enough to be absorbed by the story; but he can have had no illusions himself as to what he was actually doing.

‘Utopian biography’, then, would be a proper definition of what Xenophon created . . .

(Hägg, pp. 64 f.)

Xenophon may have written historical works but he did not confine himself to historical works. One can imagine an evangelist doing the same sort of thing with the Jesus figure. Historicity or verisimilitude takes a back seat. Those elements are a mere setting for something far more important.

Alexander the Great, Augustus, Moses, Samuel, Josephus

Nonetheless, there is no denying that ancient accounts of historical persons, and of (ahistorical) biblical figures, demonstrating some sort of outstanding wisdom or talent at a very young age do exist.

It was a culturally diffuse trope. As Cicero points out in a letter to his brother, it was not one that was necessarily believed to have been historically true. Ancient historians wrote for several reasons and one of these near the top of their lists was public entertainment. One can imagine an audience listening to such stories being entertained by them. I have to wonder how many even bothered to ask “did it really happen that way?” Our evidence does inform us that sophisticated readers were less likely to have believed such things even if they were found in some form in historical works. They made good stories, though, and if a historian also got his moral or some other propaganda message across, he was no doubt content.

Boyce, Mary. 1996. A History of Zoroastrianism: Volume 1, The Early Period. Leiden ; New York: Brill.

Feldman, Louis H. 1992. “Josephus’ Portrait of Moses.” The Jewish Quarterly Review 82 (3/4): 285–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/1454861.

Hägg, Tomas. 2012. The Art of Biography in Antiquity. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hanson, Ann Ellis. 1987. “The Eight Months’ Child and the Etiquette of Birth: ‘Obsit Omen!’” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 61 (4): 589–602.

Litwa, M. David. 2019. How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

…

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. 1891. Oratory and Orators; with His Letters to Quintus and Brutus. Translated by J. S. (John Selby) Watson. London: George Bell. http://archive.org/details/oratoryandorato00ciceuoft.

Herodotus. 1965. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey De Sélincourt. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books.

Suetonius. 2008. Lives of the Caesars. Translated by Catharine Edwards. Reissue edition. Oxford etc.: OUP Oxford.

Xenophon. 1914. The Education of Cyrus. Translated by Henry Graham Dakyns. London: J.M. Dent. https://archive.org/details/educationofcyrus00xeno

| To order a copy of How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths at the Footprint Books Website with a 15% discount click here or visit www.footprint.com.au

Please use discount voucher code BCLUB19 at the checkout to apply the discount. |

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Neil, what are the sources (or perhaps refresh my memory of Gospels) for Pilate being “known for his cruelty”? Thanks.

I always think of John Crossan’s colourful depiction of Pilate in a section headed, “That Charming Pontius Pilate” (pp. 136-140 of Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography):

Neil, thank you for this excellent and most generous explanation. I was struck by the relative mildness of the first 2 examples above. Pilate reminds me of American right wing politicians, who prefer to address problems with shows of force, rather than understanding of other cultures. But I take the point, and see its purpose within the larger argument.

Umm… the War Scroll, and other writings from Qumran; Bar Kochba, who WAS a messiah in arms. Does Crossan think he’s the BBC and can get away with lying to our faces about what is on the screen?

I don’t follow your references or what your point is, sorry.

Neil, about the cruelty of Pilate, I am not so persuaded by the usual reasons (pro-Roman apology, real historical fact, a previous Gospel story where Pilate was a vilain).

The essential goodness of Pilate, an earthly archon who “delivered” Jesus to the Jews, reflects the essential goodness of YHWH (when he “delivered” Jesus per 1 Cor 11:23), the celestial archon. If Pilate was described as essentially evil, then the celestial equivalent, the creator, had to mirror that moral corruption: not just the case, in the intentions of “Mark”.

My older post you link to is not the “usual” argument offered, as far as I am aware. The point I was making was an exploration of an alternative interpretation of what we find in the way Mark tells the story, an interpretation that tries to avoid any presuppositions from the other gospels – of from gnostic ideas such as yours.

There were also stories of the new born king being threatened in Egyptian culture. When Set heard about the birth of Horus he tried to kill him. Isis had to hide out in the thickets to protect Horus. Kings in ancient Egypt would sometimes be given mythological stories to portray them as divine or special in some way. One of these stories was the hiding out in the thickets away from harm like Horus was.

Handbook of Egyptian Mythology(Oxford University Press, 2004), Geraldine Pinch

https://www.ancient.eu/Horus/

Adela Yarbro Collins compares these stories to the woman in Revelation 12 in her book “The combat myth in the Book of Revelation”(Wipf & Stock Pub, 1976-2001).

There’s also another Egyptian story about the birth of three kings who will overthrow the current corrupt king.

The Invention of Religion: Faith and Covenant in the Book of Exodus(Princeton University Press, 2018), Jan Assmann

Just tried to post a comment but got a message telling me it was “detected as spam” for some reason. I then tried to post it again and got a message saying something like “message was already posted”. Not sure what happened.

It did get trapped in the spam filter. I try to keep a regular eye on any mistakes like that so thanks for letting me know. (This is a different scenario from the one I posted about in my “update”, by the way.)