This post is long and technical and only for those who are serious about what we can learn from the Ascension of Isaiah about early beliefs about Jesus. Richard Carrier and before him Earl Doherty drew upon scholarship about the different manuscripts to conclude that the original text had Jesus crucified in the lower heaven by demons. Roger Parvus, however, has argued a different interpretation from what we can glean from the different manuscript traditions (in particular the Ethiopic with its lengthy account beginning with Jesus’ birth to Mary and the second Latin, L2, with its “absurdly brief” account of Jesus dwelling with men, full stop) and I have copied his argument below. For the original posts in context see parts 7 and 8 at Roger Parvus: A Simonian Origin for Christianity.

As for my own views, I am withholding judgement until I collect a few more publications, in particular the ten articles or essays that Enrico Norelli published as “addendums” to his commentary: Norelli, Enrico. 1995. Ascensio Isaiae: commentarius. Turnhout: Brepols. (If anyone can help me gain access to those ten essays – I understand they are all in Italian – please please do contact me!)

What follows are copies of one small section of A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 7: The Source of Simon/Paul’s Gospel and the full text of A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 8: The Source of Simon/Paul’s Gospel (continued) — all written by Roger Parvus, not me.

–o0o–

Where?

But where, according to the Vision, did the hanging upon a tree occur? The Son will “descend into the world” (according to 9:13, in some versions of E) and “will be in the world” (per 10:7, in L2), but in no uncontroversial section of the extant text does it explicitly say which part of the world. I am inclined to think the location was understood to be on earth, not in its sublunary heaven. For one thing, 9:13 goes on to say that the Son “will become like you [Isaiah] in form, and they will think he is flesh and a man.” Earth is the home of men of flesh and so it is presumably there that the Son could expect to fool the rulers of the world into thinking he was a man.

I realize one could object that the Son’s persecutors appear to be the spirit rulers of the world and that their home was thought to be in the firmament. But it was also commonly accepted that their rule extended to earth and below it, and that they could exercise their power through human instruments. That is what we see right in the Martyrdom of Isaiah. Beliar kills Isaiah through King Manasseh:

Because of these visions, therefore, Beliar was angry with Isaiah, and he dwelt in the heart of Manasseh, and he cut Isaiah in half with a saw… Beliar did this to Isaiah through Belkira and through Manasseh, for Sammael was very angry with Isaiah from the days of Hezekiah, king of Judah, because of the things he had seen concerning the Beloved, and because of the destruction of Sammael which he had seen through the Lord, while Hezekiah his father was king. And he did as Satan wished. (Asc. Is. 5:1 & 15-16)

True, as already mentioned, parts of the Martyrdom were written after the Vision. But it is nevertheless still a quite early writing, likely dating to the end of the first century. It does not quote or allude to any New Testament writings. But it does clearly allude to the Vision and so may provide us with an indication of how that writing was understood by at least one first century Christian community. If the Martyrdom portrays the rulers of the world attacking Isaiah through a human instrument, this may very well have been the way the prophesied attack on the Son of the Vision was understood too, for he was to become like Isaiah in form (Asc. Is. 9:13) and trick them into thinking he was flesh and a man.

Another consideration that leads me to think the Son’s death in the Vision occurred on earth is the way Irenaeus speaks of Simon of Samaria. One would think, based on what Irenaeus says, that Simon knew the Vision of Isaiah and claimed to be the Son described in it. And in his account the location of the Son’s death is specified as Judaea:

For since the angels ruled the world ill because each one of them coveted the principal power for himself, he [Simon] had come to amend matters, and had descended, transformed and made like the powers and authorities and angels, so that among men he appeared as a man, though he was not a man, and he seemed to suffer in Judaea, though he did not suffer (Against Heresies, 1, 23, my bolding).

In the Panarion of Epiphanius the reason why Simon made himself like the powers is spelled out. Simon is quoted as saying:

In each heaven I changed my form, in order that I might not be perceived by my angelic powers… (2, 2)

It seems to me that in the first passage Irenaeus is relaying an early claim made by Simon, and he is relaying it in the words that Simon or his followers used, not those of Irenaeus. The one “who suffered in Judaea” is not an expression that Irenaeus uses anywhere else to describe Christ. And the claims attributed to Simon in the passage look primitive.

- He doesn’t claim to be the Son who taught and preached in Galilee and Judaea;

- or who worked great signs and wonders among the Jews;

- or who gathered together a band of disciples.

- He doesn’t say he was the Christ who came to lay down his life to atone for the sins of mankind.

The limited claims attributed to him in the passage are reminiscent of the information about the Son in the Vision of Isaiah. Assuming that was Simon’s source, the place where the Son’s suffering was believed to have occurred is specified as Judaea.

–o0o–

.

| In the previous post of the series I proposed that the Vision of Isaiah was the source of Simon/Paul’s gospel.

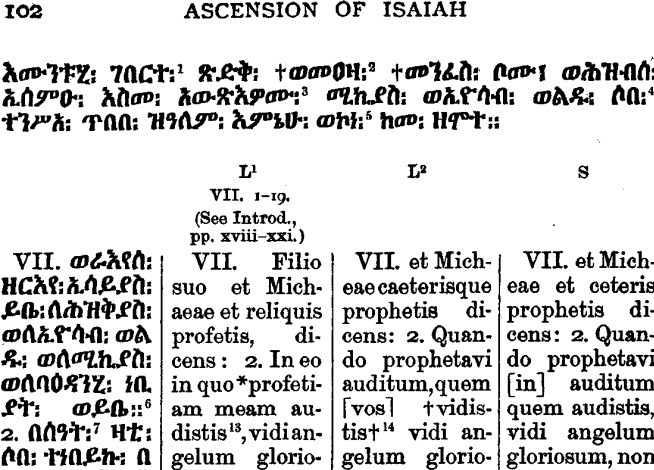

This post will look at the place in the Vision that contains the major difference between the two branches of its textual tradition. Obviously, at least one of the readings is not authentic. But, as I will show, there are good reasons to think that neither reading was part of the original.

|

.

The passages in question are located in chapter 11 of the Vision. In the L2 and S versions the Lord’s mission in the world is presented by a single sentence:

2… And I saw one like a son of man, and he dwelt with men in the world, and they did not recognize him.

In place of this the Ethiopic versions have 21 verses, 17 of which are devoted to a miraculous birth story:

2 And I saw a woman of the family of David the prophet whose name (was) Mary, and she (was) a virgin and was betrothed to a man whose name (was) Joseph, a carpenter, and he also (was) of the seed and family of the righteous David of Bethlehem in Judah. 3 And he came into his lot. And when she was betrothed, she was found to be pregnant, and Joseph the carpenter wished to divorce her. 4 But the angel of the Spirit appeared in this world, and after this Joseph did not divorce Mary; but he did not reveal this matter to anyone. 5 And he did not approach Mary, but kept her as a holy virgin, although she was pregnant. 6 And he did not live with her for two months.

7 And after two months of days, while Joseph was in his house, and Mary his wife, but both alone, 8 it came about, when they were alone, that Mary then looked with her eyes and saw a small infant, and she was astounded. 9 And after her astonishment had worn off, her womb was found as (it was) at first, before she had conceived. 10 And when her husband, Joseph, said to her, “What has made you astounded?” his eyes were opened, and he saw the infant and praised the Lord, because the Lord had come in his lot.

11 And a voice came to them, “Do not tell this vision to anyone.” 12 But the story about the infant was spread abroad in Bethlehem.

13 Some said, “The virgin Mary has given birth before she has been married two months.” 14 But many said, “She did not give birth; the midwife did not go up (to her), and we did not hear (any) cries of pain.” And they were all blinded concerning him; they all knew about him, but they did not know from where he was.

15 And they took him and went to Nazareth in Galilee. 16 And I saw, O Hezekiah and Josab my son, and say to the other prophets also who are standing by, that it was hidden from all the heavens and all the princes and every god of this world. 17 And I saw (that) in Nazareth he sucked the breast like an infant, as was customary, that he might not be recognized.

18 And when he had grown up, he performed great signs and miracles in the land of Israel and (in) Jerusalem.

19 And after this the adversary envied him and roused the children of Israel, who did not know who he was, against him. And they handed him to the ruler, and crucified him, and he descended to the angel who (is) in Sheol. 20 In Jerusalem, indeed, I saw how they crucified him on a tree, 21 and likewise (how) after the third day he and remained (many) days. 22 And the angel who led me said to me, “Understand, Isaiah.” And I saw when he sent out the twelve disciples and ascended.

(M. A. Knibb, “Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, pp. 174-75.)

One Substitution or Two?

Most scholars think the L2 and S version of the Lord’s earthly mission is far too brief to be original. The foreshadowing in the Vision “expects some emphasis on the Beloved assuming human form as well as some story of crucifixion” (p. 483, n. 56). But instead L2 and S give us what looks like some kind of Johannine-inspired one-line summary: “he dwelt with men in the world” (cf. Jn. 1:14). Those who think the Ethiopic reading represents the original see the L2 and S verse as a terse substitution inserted by someone who considered the original to be insufficiently orthodox.

But from the recognition that 11:2 of the L2/S branch is a sanitized substitute, it does not necessarily follow that 11:2-22 in the Ethiopic versions is authentic. That passage too is rejected by some (e.g., R. Laurence, F.C. Burkitt). And although most are inclined to accept it as original, they base that inclination on the primitive character of its birth narrative. Thus, for example, Knibb says “the primitive character of the narrative of the birth of Jesus suggests very strongly that the Eth[iopic version] has preserved the original form of the text” (“Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, p. 150)

It is true that the Vision’s birth narrative, when compared to those in GMatthew and GLuke, looks primitive. But there are good grounds for thinking that the original Vision did not have a birth narrative at all. A later substitution is still a later substitution even if it is a birth narrative that is inserted and its character is primitive compared to subsequent nativity stories. Robert G. Hall sensed this and in a footnote wrote:

Could the virgin birth story have been added after the composition of the Ascension of Isaiah? Even if we conclude that this virgin birth story was added later, the pattern of repetition in the Vision probably implies that the omission of 11:1-22 in L2 and Slav is secondary. The foreshadowing expects some emphasis on the Beloved assuming human form as well as some story of crucifixion. Could the story original to the text have offended both the scribe behind L2 Slav and the scribe behind the rest of the witnesses? The scribe behind the Ethiopic would then have inserted the virgin birth story and the scribe behind L2 Slav would have omitted the whole account. The virgin birth story is, however, very old and perhaps it is best not to speculate. (“Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, n. 56, p. 483, my bolding)

I agree that both the E and L2/S readings at 11:2 could be replacement passages, but I think Hall’s advice not to speculate should be disregarded, for it is his very observations about the Vision that provide some good reasons to suspect that 11:2-22 did not belong to the original text. It is he who points out that foreshadowing and repetition characterize the Vision—except when it comes to the birth story!

As a proper understanding of the goal and narrative structure of the Vision tie the work together, so do a number of stylistic and rhetorical devices. The author uses repetition to unify the work, yet introduces variations in patterns to reduce the monotony. The effect is analogous to that in the musical form known as “variations on a theme.” The variations often foreshadow later discussions. This anticipation, together with the events anticipated, contributes in turn to the author’s scheme of repetition, with the result that hardly anything of importance in the vision is not mentioned at least twice… [I]n every case what the angel announces Isaiah will see, Isaiah sees. The pattern of repetition is so complete that I think it is safe to say that there is nothing in the Vision that is not mentioned at least twice. (“Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, pp. 480 and 481, my bolding)

Except, that is, the miraculous birth story:

Although I see no major aberrations in this carefully structured work, one minor interruption in the pattern does occur. Although the angel foreshadows that the Beloved transforms “until he resembles your appearance and your likeness” (8:10; cf. 9:13), nothing prepares for the virgin birth story in 11:1-16. Given the pattern of repetition in the work, some explanation of the transformation of the Beloved into human form is necessary, but I find it surprising that virgin birth should be elaborated at such length without anticipation. (pp. 482-3, my bolding)

Hall guesses that perhaps the author wanted to emphasize the transformation “by introducing his first and only surprise” (p. 483). But that guess does not really solve the problem. For it is not just the nativity’s presence in the Vision that stands out as an anomaly; its absence from the rest of the Ascension as a whole is hard to explain. The chronologically later parts of the Ascension that allude to the Vision make no mention of it. Thus the summary of the Vision situated at the beginning of the 3:13 – 4: 22 interpolation says nothing about a miraculous birth or the Lord’s transformation into a baby:

For Beliar was very angry with Isaiah because of the vision, and because of the exposure with which he had exposed Sammael, and that through him there had been revealed the coming of the Beloved from the seventh heaven and his transformation, and his descent, and the form into which he must be transformed, (namely) the form of a man, and the persecution with which he would be persecuted, and the torments with which the children of Israel must torment him… (Asc. Is. 3: 3a, my bolding)

Nor does the birth show up in the redactional summary of the Vision at the beginning of the Ascension:

And he (Hezekiah) handed to him (Manasseh) the written words which Samnas the secretary had written out, and also those which Isaiah the son of Amoz had given to him and to the prophets also, that they might write out and store up with him what he (Isaiah) had seen in the house of the king concerning the judgment of the angels, and concerning the destruction of this world, and concerning the robes of the saints and their going out, and concerning their transformation and the persecution and ascension of the Beloved. (Asc. Is. 1:5b).

Hall puts it this way:

In composing the Ascension of Isaiah, the author alludes to doctrines behind most of the Vision of Isaiah… Lists of appropriate revelations allude to most of the elements in the vision. (“Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, p. 474).

But, notes Hall:

I can think of only two major exceptions: nowhere does the author mention the proof that what is done on earth is known in heaven (7:25-27; 9:19-23) and nowhere does the author allude to the virgin birth story (11:1-16)[n. 46, p. 474, my bolding].

The total omission of any reference to the Lord’s miraculous birth is puzzling for, as Hall points out, the birth is “elaborated at such length” (16 verses) in the Vision. How did it apparently escape the radar of the author of the Ascension when he alludes to so many other elements of the Vision? The answer, I suspect, is that the nativity wasn’t in the Vision when the Ascension incorporated it. Something else was.

A Speculative Proposal

Since a birth account is totally missing from the L2 and S branch of the textual tradition, and since the birth account that is in the Ethiopic branch constitutes both an interruption to the pattern of the Vision and an exception to the lists of revelations that appear elsewhere in the Ascension, I think it is justifiable to speculate that originally there was a different passage present at 11:2-22.

I would like to propose one whose contents

- take into account the foreshadowing and transformations in the Vision, and

- combine this with an early Basilidean teaching about a double transformation that occurred on the road to Golgotha.

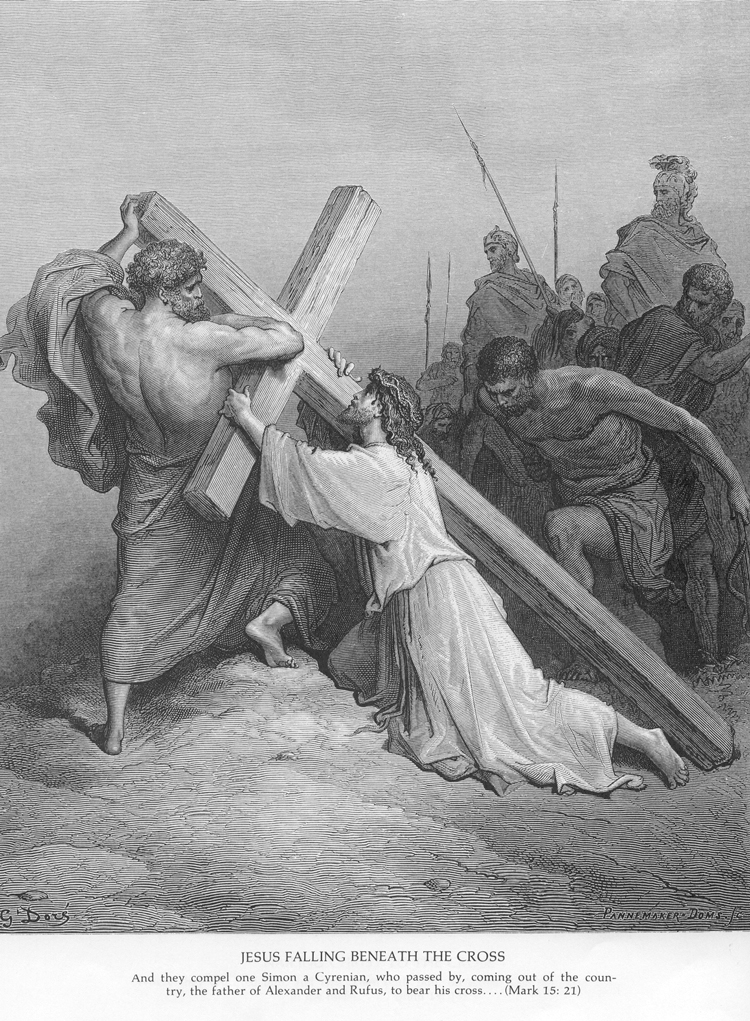

I suspect that the Vision had the Lord enter the world not as a baby at Bethlehem, but as an adult just outside the city of Jerusalem. And that via another transformation he proceeded without delay to his goal: crucifixion by the rulers of the world. The passage I envision for the 11:2-22 slot went something like this:

I saw the Lord descend into the world, transforming himself and becoming like a son of man. And the rulers of this world did not know who he was. And as he was coming into Jerusalem from the country, soldiers were leading a rebel out to crucify him. The children of Israel had risen up against the man and handed him over to the ruler. The soldiers compelled the Lord to carry the man’s cross and brought him to the place of crucifixion. And transforming himself the Lord took on the appearance of the other and, in turn, made the man look like himself. And the transformations were hidden from the rulers of this world.

Neil here, interrupting Roger Parvus’s post: I tentatively propose that the line about Jesus drinking the wine while on the cross was not part of the original Asc. Isa. but was added by the Markan evangelist as part of a larger Roman Triumph irony around which he structured the entire crucifixion scene.Then I saw that they crucified the Lord. It was the third hour on the day before the Sabbath when they crucified him. They gave him wine drugged with myrrh, but he did not take it. They crucified him and divided his garments, casting lots on them, what each should take. The inscription of the charge against him read, “The King of the Jews.” With him they crucified two robbers, one on his right and one on his left. Those passing by reviled him, shaking their heads and saying, “Save yourself, if you are the son of God, and come down from the cross.” Likewise the chief priests, with the scribes, mocked him among themselves and said, “He saved others; himself he cannot save. Let the Christ, the King of Israel, come down now from the cross that we may see and believe.” And those too who were crucified with him insulted him.

At the sixth hour darkness came over the whole land until the ninth hour. And at the ninth hour he cried out with a loud voice and breathed his last. When the centurion who stood facing him saw how he breathed his last he said, “Truly this man was a son of God!” When it was evening he was taken down from the cross and buried. And I saw him transform himself and descend to Sheol and plunder there the angel of death. On the third day he rose bringing many of the righteous with him.

The proposed passage takes into account

- that, as noted by Hall, “The foreshadowing expects some emphasis on the Beloved assuming human form as well as some story of crucifixion” (“Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, p. 483, n. 56).

The foreshadowing in the Vision also anticipates

- that the ruler of this world will fail to recognize the Lord he crucifies (9:14).

My proposal duly emphasizes these items.

It also can account for

- how the Lord came to be called “Jesus” and “Christ” in the world. The emergence of those names for him is apparently foreshadowed too in the Vision, for he is the one “who is to be called in the world Jesus” (9:5); “who is to be called Christ after he has descended” (9:13).

Although those are sometimes viewed as secondary insertions, it may be that they were part of the original Vision. The idea would be that the heavenly Lord—the true Savior and King—acquired those appellatives as the ironic result of his surreptitious switch of places with a would-be earthly savior (“Jesus”) and anointed one (“Christ”).

My proposed passage has recourse to a belief in a double transformation that, according to Irenaeus, goes back at least to Basilides, a pupil of the Simonian Menander.

My proposed passage has recourse to a belief in a double transformation that, according to Irenaeus, goes back at least to Basilides, a pupil of the Simonian Menander.

Irenaeus describes the double transformation thus:

Wherefore also he did not suffer, but a certain Simon, a Cyrenian, was compelled to carry his cross for him; and this one was crucified through ignorance and error, having been transformed by him, so that he was thought to be Jesus himself. Jesus, however, took on the form of Simon, and stood by laughing at them… Therefore those who know these things have been set free from the rulers who made the world. (Against Heresies 1, 23, 4)

Now it is true that, as Irenaeus describes it, the transformations in question resulted in the Lord’s escape from crucifixion. But Irenaeus has almost certainly mixed up the parties involved. Why would anyone think the crucifixion of a merely human passer-by would be salvific? Surely Basilides was aware that wrongful executions had happened before and will happen again. And what kind of monster would his Lord be if he was laughing while an innocent was getting crucified in his place?

No, it is much more likely that the two transformations were viewed as the means whereby the rulers of this world were tricked into crucifying the Lord. The one who “was crucified through ignorance and error” was the Lord of glory, as in 1 Corinthians 2:8. The one who escaped crucifixion was the insurgent. And if we put ourselves in Irenaeus’ shoes, we can see how it was almost inevitable that he would misunderstand the double transformation. For he was writing towards the end of the second century when all the gospels—gnostic and orthodox alike—possessed a Jesus who had engaged in a public ministry on earth. And in them the Lord, having completed his public ministry, was arrested and led out for crucifixion. So from the perspective of Irenaeus, if Basilides taught that some kind of double transformation occurred on the road to Golgotha, the Lord had to have been the escapee. I think Irenaeus was mistaken and that his mistake was induced by the development (i.e., a public ministry for the Lord) that the initial gospel had undergone about fifty years before his time.

The Markan Connection

Now scholars have noticed that there is a careless use of pronouns at the point in the Markan passion account that deals with the passer-by. As a result of the negligence, the Markan account “could be read in a way that appears to give some support for Basilides’ assertion that not Jesus but Simon of Cyrene was crucified” (Jesus, Gnosis and Dogma, Riemer Roukema, p. 109).

After Simon of Cyrene was introduced there, it is written that they brought ‘him’ to Golgotha and crucified ‘him’ there (Mark 15:21-24). Read in context, it becomes clear that ‘him’ refers to Jesus, because previously it is written, ‘Then they led him out to crucify him’ (Mark 15:20), and this is unmistakably about Jesus. In the transition from Mark 15:21 to Mark 15:22, the evangelist has neglected to indicate, however, that he did not mean Simon, but Jesus who was brought to Golgotha. In this way, this gnostic exegesis could be invented. (Jesus, Gnosis and Dogma, Riemer Roukema, pp. 109-10, my bolding).

Thus, it is argued, the context of the pronoun ‘him’ in Mk. 15:21 makes it clear that the one who was crucified was the one who is the subject of Mark’s Gospel, for “the story is mainly about Jesus, and it is clear that Jesus is the one being taken to Golgotha to be crucified” (Mark—A Commentary, Adela Yarbro Collins, p. 734). But many scholars also acknowledge that the author of GMark adapted a pre-Markan passion narrative. So the question becomes: What was the original context of that narrative? Was it the Vision of Isaiah? It may be that, as the Pauline letters seem to indicate, its crucified Lord did not spend a lifetime on earth and did not have a public ministry. If the earthly phase of the Lord’s mission in the original gospel consisted only of his incognito entry into the world for crucifixion, the double transformation on the way to Golgotha would make sense as his entry point to that goal. The loose Markan pronouns and the teaching attributed to Basilides may be surviving traces of that original entry point.

Why Replaced?

Assuming that the original Vision had the Lord enter the world in the way I have proposed, a natural question is: Why did someone later substitute an entry via miraculous birth?

My tentative thought is that in time the original passage may have come to be viewed as too sympathetic to the Jewish zealot cause. After all, in it the Lord does swap places with someone who tried, presumably by violent means, to set himself up as king of the Jews. I very much doubt that the author of the Vision condoned violent measures. If that was one of his purposes, I think it would have been reflected in the later parts of the Ascension of Isaiah, especially in the interpolation where Nero’s rule over the world is described (Asc. Is. 4:1-13). Even there the text issues no call to take up arms in resistance. Nevertheless, since the switching incident could easily be interpreted as sympathetic to Jewish rebels, it may have later been deemed unacceptable.

In my proposal for the 11:2-22 slot the Lord swaps places with a rebel who is scorned by the Jerusalem Jews, including their chief priests and scribes. They make fun of the rebel’s claims to be an anointed one (a Christ), a king, a son of God who would save them. Their lack of sympathy for their would-be savior is reminiscent of the people’s animus against the many Jews who laid claim to kingship after the death of Herod the Great in 4 BCE:

And now Judaea was full of robberies; and, as the several companies of the seditious lighted upon anyone to head them, he was created a king immediately, in order to do mischief to the public. They were in some small measure indeed, and in small matters, hurtful to the Romans, but the murders they committed upon their own people lasted a long while (Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 17, 10, 8, my bolding).

The parallel in The Wars of the Jews reads:

At this time there were great disturbances in the country, and that in many places; and the opportunity that now offered itself induced a great many to set up the kings… (Wars 2, 4, 1, my bolding)

When Varus came from Syria and lifted the rebel siege of Jerusalem, the citizens of the city made clear that they “were on the side of the Romans” (Antiquities 17, 11, 9) and were themselves very much victims of the rebels. Varus agreed and sent his army out into the country to apprehend those behind the rebellion. Great numbers of them were caught. Varus put the least culpable in custody, but the most guilty he crucified, “in number about 2000” (Wars 2, 5, 2), with the apparent approval of the citizens of Jerusalem.

To me it seems plausible that the Vision of Isaiah was written in the aftermath of that tumultuous period. The author had no particular would-be king in mind, and no particular love for any of them. The situation merely provided him with a mechanism for getting the Lord crucified by the rulers of this world. But in time that mechanism may have become an embarrassment to some. It is one thing to have the Lord falsely accused of being a lestes (as in the later canonical gospels) and another to have him actually trade places with a guerilla leader, getting the would-be king off the hook in the process.

In the account that is currently lodged in the Ethiopic versions there is little trace of rebellion. The Lord enters the world as a baby. And when the time comes for his crucifixion it is simply said that: “after this the adversary envied him and roused the children of Israel, who did not know who he was, against him” (11:19). There are no taunts that he claimed to be a king of the Jews or to save them. Neither the Romans in general, nor any Roman in particular is mentioned. No particular grounds for the crucifixion are provided.

Transformation and Crucifixion

In the references that the Pauline letters make to the earthly phase of the Lord’s mission the stress, as acknowledged by all, is clearly on the crucifixion. Apart from that, attention is given in the Philippians hymn to the Lord’s change of form, but there too the transformation is brought into immediate connection with his death: “And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself, becoming obedient unto death, even death on the cross” (Phil. 2:8). The hymn apparently has the Lord take on the form of a man, not to teach, work miracles, or gather disciples, but to die. And it is apparently the same transformation that is behind the failure of the rulers of this world, as related by 1 Cor. 2:8, to recognize the Lord of glory when they crucified him. Transformation and crucifixion, then, are almost exclusively the elements of the Lord’s visit to earth that can be found in the uncontroversial parts of the Pauline letters.

And it is not just that there is no public ministry. As Earl Doherty pointed out in Jesus: Neither God Nor Man, pretty much the rest of the passion narrative as found in the canonical gospels is missing too. No scourging or crowning with thorns, no betrayal by Judas, or denials by Peter, or abandonment by the disciples, or preference of Barabbas over Jesus. Besides the crucifixion, arguably the only other reference to a passion incident is the mention of “insults” in Rom. 15:3.

My speculative proposal can explain this situation. Those in Rom. 15:3 who insulted him (oneidizō) are the same who insulted him on the cross: “Those who were crucified with him also insulted (oneidizō) him” (Mk. 15:32). The names Christ and Jesus—which have practically become personal names by the time the first Pauline letters were written—were originally ascribed to the Lord because of his surreptitious swapping of appearance with a would-be Christ and Jesus (Savior) who was being led out of Jerusalem for crucifixion. That transformation was immediately followed by the Lord’s crucifixion. The reason that transformation and crucifixion are practically the only elements of the Lord’s visit to earth that can be found in Paul’s letters is because one immediately followed the other in the source of his gospel: the Vision of Isaiah.

I have left out of my speculative proposal parts of GMark that are arguably later redactional additions, including the cast of named characters: Simon the Cyrenian who is the father of Alexander and Rufus, Mary the Magdalene, Salome, Mary the mother of Joses and James the Small. In a subsequent post I will argue that these were Simonian additions to the original passion narrative. They Simonized it. And I will also argue that the incidents that immediately precede the passer-by in GMark—the Last Supper, betrayal by Judas, denials by Peter, abandonment by the disciples, and preference of Barabbas over Jesus—are allegorical portrayals of events from the last trip of Simon/Paul to Jerusalem. The release of Jesus Barabbas—the son of the father— by Pilate is an allegorical portrayal of the release of Simon/Paul by Felix. The release of Barabbas would function as the seam that separated the allegory about Simon/Paul from the earlier story of the Son’s crucifixion. If this is correct, the only transitional verses that join the allegory to the crucifixion are Mk. 15:16-20 i.e., the crowning with thorns of the king of the Jews and the mockery of him by the soldiers. This transitional material may have been taken from Philo’s account of the mockery of Carabbas (In Flaccum, 6, 36-9).

But before coming to Mark’s Gospel I will devote one more post to the Vision of Isaiah.

–o0o–

To see that “one more post” go to A Simonian Origin for Christianity, Part 9: The Source of Simon/Paul’s Gospel (conclusion)

–o0o–

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I am very impressed with and grateful to Neil for his diligent work in this area which is key in the study of the origins of Christianity, accounting for the disconnect between the Gospels + Acts and the rest of the New Testament. I am looking forward to reading further scholarly input.

Not have which add on it what is being Peter Grullemans already would say: I am very impressed with and grateful to Neil for his diligent work in this area which is key in the study of the origins of Christianity,…This is only another in a row extraordinary Neil’s texts which me especially has interested, and all they read regularly . Greeting for Neil and for all increasing escorts and readers.

Zdenko Pajnić, Belgrade

Please understand that the above post is a copy of earlier guest posts by Roger Parvus. We can be thankful to Roger Parvus for his series of posts on this blog:

https://vridar.org/other-authors/roger-parvus-a-simonian-origins-for-christianity/

https://vridar.org/other-authors/roger-parvus-letters-supposedly-written-by-ignatius/

But from the recognition that 11:2 of the L2/S branch is a sanitized substitute, it does not necessarily follow that 11:2-22 in the Ethiopic versions is authentic. That passage too is rejected by some (e.g., R. Laurence, F.C. Burkitt).

• 11:2-22 in the Ethiopic versions is also rejected by Dillmann, Harnack, Schürer, Deane and Beer.

per “1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Isaiah, Ascension of“. Wikisource. Retrieved 31 October 2018. [now bolded]:

Though some scholars more recently have accepted 2-22 as original there have long been reasons for rejecting it as a later addition: stylistic, contextual, thematic.

Again I am so glad you guys are doing the spade work on all this, while I can only comment. I am interested in how the epistles, not the Gospels, relate to the Asc. Is. and I may have more to say about this later. The angelology in Asc. Isa. as well as in the Book of Enoch seem to me consistent with the Jesus Myth theory. Paul’s reference to a man having been transported to the third heaven in 2 Cor.12:2 seems to be a relic of the Asc. Is. and Enochian experiences. The book of Revelation also seems to echo the themes of the spiritual beings doing battle. I wonder how Christianity can even be relevant today in Western societies that do not empathise with or appreciate similar swirling tides of the political and religious systems of first century Palestine.

There are indeed studies that draw attention to the links joining all of those writings that you mention.

Per “Ascension of Isaiah | pseudepigraphal work“. Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 July 1998.

If we are going to let the wild horses run, then perhaps I will have a turn:

The original crucifixion content was no doubt highly embarrassing if not outright heretical to later Christians. I think there is a narrative theme that underpins the Asc. and that is the martyrdom of Isaiah, it is the central premise.

Having received the vision, Hezekiah offers to have his son killed, but Isaiah rejects this solution. So Isaiah’s suffering has to be important.

If Asc. is Paul’s gospel, then perhaps we can reproduce some of its content from Paul’s letters. Jesus must be handed over, and his body is broken. Paul seems to reference the ‘suffering servant’ in Philippians ‘by taking the very nature of a servant’. The Ethiopian eunuch asks if the suffering servant is “…about himself or about someone else?”.

Finally, Asc. spells out in plain words:

“In Jerusalem indeed I was Him being crucified on a tree:”

So accordingly, I surmise that Christ descended into the body of Isaiah just before he is sawn asunder and that was the actual crucifixion scene. If there is some form of switcheroo here, it is the Christ spirit taking over the body when Isaiah describes his eyes being open but not seeing. But this is not the fully developed switcheroo, and I don’t think Paul’s letters suggest a literal body switch, (which may have developed later).

Note also that Isaiah is accused of blaspheming by contradicting the law of Moses in saying he has seen the face of God and lived – which would seem to denigrate the law of Moses in this context.

So if this wild horse is allowed to run free, we have a possible crucifixion occurring on Earth during the reign of Manasseh, in which Jesus takes over Isaiah’s body at his martyrdom. Or, we still have a crucifixion occurring in the firmament which parallels Isaiah’s martyrdom on Earth. I think the former more likely here, as simultaneous events in both realms is well, overkill!

So if Isaiah is interpreted to be the ‘suffering servant’ which gave birth to the Christ myth, then we also have the other story about a stream of water emerging from the place of his death. This seems to be a common motif about Jesus also (streams of living water), and interestingly Yeshu was buried in a stream.

The problem with this theory is that it would elevate Isaiah from prophet to god-man, and if this were the case, we don’t see many clues in other Christian writings. We don’t have Iraneous mentioning any such heresy! Is it possible the missing crucifixion content was never part of the document – it was kept separately? but then why did ‘I was Him’ get inserted with the pocket gospel?

OK – time to reign this wild horse in!