[A]ll we need for the case for the historicity of Jesus to be solid is some evidence that weighs strongly in favor of his historicity. And we have it, and so in theory, mythicism should simply vanish. But as with all forms of denialism, it will persist regardless of the evidence.

— McGrath, Jesus Mythicism: Two Truths and a Lie

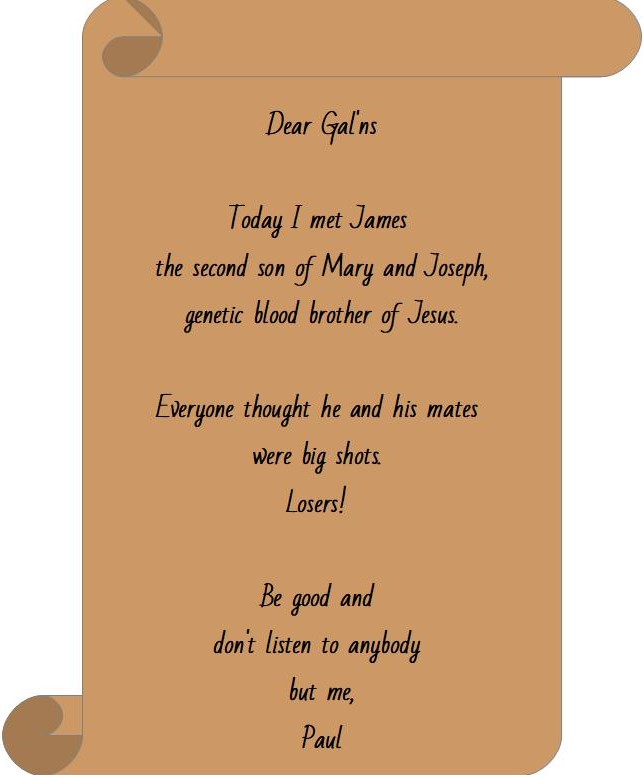

There was some question in the comments of my initial response as to what that solid evidence was that James McGrath had in mind. I responded as if he were addressing Paul’s claim to have met James “the brother of the Lord” — both here and again here.

McGrath has since made it clear:

But the point remains: if we have an authentic letter from someone who met an individual’s brother, and we judge that individual’s historicity probable on that basis, the addition of spurious information does not diminish the likelihood that the letter-writer met the brother of that individual and thus was in a position to know whether they were historical or not. If everything else they learned about that individual was pure fabrication, it would diminish the historical accuracy of their portrait of him, but it would not diminish the likelihood of the individual’s historicity.

I’m not going to repeat the points I have made before about the problems with detail after detail in Carrier’s argument (such as when he treats the common name Joshua/Jesus as though it were a too-convenient name for a savior god – begging the question by casting Jesus as a god and not a human being as Davidic anointed ones were expected to be). Let ms simply conclude by quoting what Carrier says on p.337 of his book that I supposedly have not read: “Obviously, if Jesus Christ had a brother, then Jesus Christ existed.”

— McGrath, Mythicist Math

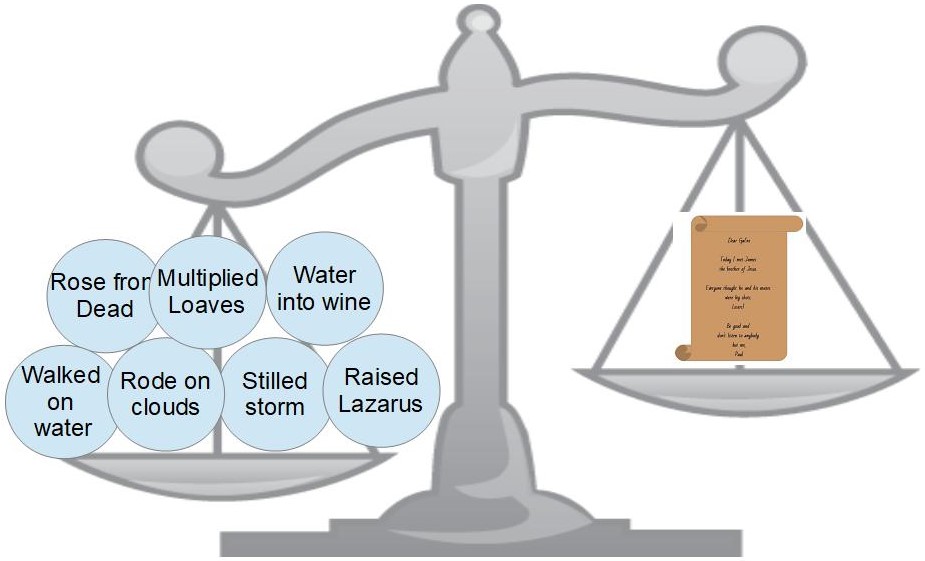

That would indeed be strong evidence if in fact Paul did meet “James the brother of the Lord” and it would end any debate over mythicism.

But even Philip R. Davies recognized the evidence is not so simple:

I don’t think, however, that in another 20 years there will be a consensus that Jesus did not exist, or even possibly didn’t exist, but a recognition that his existence is not entirely certain would nudge Jesus scholarship towards academic respectability. In the first place, what does it mean to affirm that ‘Jesus existed’, anyway, when so many different Jesuses are displayed for us by the ancient sources and modern NT scholars? Logically, some of these Jesuses cannot have existed. So in asserting historicity, it is necessary to define which ones (rabbi, prophet, sage, shaman, revolutionary leader, etc.) are being affirmed—and thus which ones deemed unhistorical. In fact, as things stand, what is being affirmed as the Jesus of history is a cipher, not a rounded personality (the same is true of the King David of the Hebrew Bible, as a number of recent ‘biographies’ show).

So is it sheer “denialism” that prevents some of us from accepting the “solid evidence” of Paul’s encounter?

There have been attempts to use the full Bayesian formula to evaluate hypotheses about the past, for example, whether miracles happened or not (Earman, 2000, pp. 53–9). Despite Earman’s correct criticism of Hume (1988), both ask the same full Bayesian question: “What is the probability that a certain miracle happened, given the testimonies to that effect and our scientific background knowledge?” But this is not the kind of question biblical critics and historians ask. They ask, “What is the best explanation of this set of documents that tells of a miracle of a certain kind?” The center of research is the explanation of the evidence, not whether or not a literal interpretation of the evidence corresponds with what took place.

Tucker, Our Knowledge of the Past, p. 99

And it goes exactly the same way for the testimony that we read in Galatians 1:19. No, it is not simply dismissing uncomfortable passages as interpolations. It is about exercising responsible historical criticism and testing of the evidence as all sound historical method requires. The alternative is naive apologetics or uncritically furthering tradition. There are indeed reasonable grounds for doubting that that verse was known to anyone before the third century. There are also reasons to doubt that anyone had any idea that James, a brother of the Lord, was indeed a leader of the Jerusalem church until the third century. There are good reasons to suspect the passage was introduced to serve the interests of an emerging “orthodoxy” against certain “heresies”. See the posts in the Brother of the Lord archive for more detail.