Ever since the early 1960s biblical scholars and even psychologists have been told something very critical about the apostle Paul’s teachings that had the potential to spare the mental sufferings of so many Western Christians. Paul did not teach that one had to go through self-loathing or guilt-torment in order in order to be saved by faith in Christ’s forgiveness. That guilt-focused teaching came to us primarily via Augustine and Luther. It was a teaching that can nowhere be found in reference to Paul in the first 350 years of Christianity.

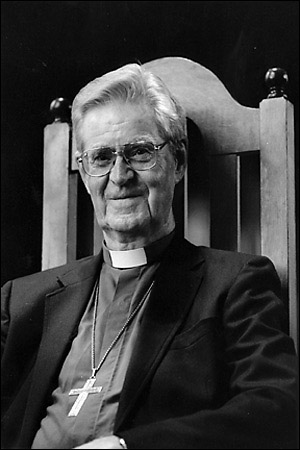

That is the argument of Krister Stendahl in a paper, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West” (The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jul., 1963), pp. 199-215) said to be a watershed in Pauline studies. But the real-world relevance of the paper is indicated by the fact that it was first delivered two years earlier “as the invited Address at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, September 3, I961.”

I’ve had the paper sitting in my files waiting to be read for some time now, and only dug it out after seeing it cited by James W. Thompson in The Church According to Paul: Rediscovering the Community Conformed to Christ (2014).

Paul, Thompson claimed, never addressed personal struggles with tormented conscience that could only be resolved by desperately throwing oneself upon the mercy of Christ:

The first-person singular pronoun is a consistent feature of church music in the evangelical tradition.

Amazing grace, how sweet the sound

that saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now, found,

Was blind but now I see.

Like countless other songs in this tradition, “Amazing Grace” tells of the individual who was lost in sin, unable to meet God’s demands until Jesus paid it all at the cross. These songs echo Pauline themes of sin, grace, and justification. Indeed, Paul’s legacy is the good news that we have been “justified by faith’ (Rom 5:11. not by our own works (cf. Rom. 3:20, 28; 4:2). In the cross God demonstrated righteousness for all who believe (Rom. 3:21-26). The death of Christ “while we were yet sinners” (Rom 5:8 KJV) was the expression of God’s love.

Interpreters have maintained that this narrative mirrors Paul’s own experience. According to this view, Paul struggled with a guilty conscience, having attempted in vain to keep the law perfectly. The “wretched man”(Rom. 7:24) who could not do the good or keep the law was Paul himself, who lived within the context of a form of Judaism that had degenerated into a legalistic and hypocritical religion that no longer recognized the mercy of God and instead emphasized meritorious works. Paul then found the answer in the grace of God and recognized that God justifies the ungodly. Paul has often been regarded as paradigmatic for those who discovered God’s grace when they could not keep God’s commands. When he met Christ on the Damascus road, he experienced God’s grace. Out of this experience, he became the example of the path of conversion for all subsequent generations and the major theme of his writings is justification by faith. This view has been emphasized in Protestant theology, becoming the popular theme of revivalists and Christian song writers.

Krister Stendahl observed that the Pauline doctrine of justification by faith did not emerge as the center of Paul’s theology until Augustine, who himself turned to Paul after struggling with a guilty conscience. Augustine found the solution to his own personal struggle in the grace of God! Luther also discovered the grace of God as the solution to his own desire to find a merciful God. Beginning with Luther, the Reformers maintained that Paul’s doctrine of the righteousness of God was the center of the gospel. This doctrine has been conceived in individualist terms. . . . For numerous Protestant theologians, justification was the salvation of the individual. . . . The good news is the righteousness of God that rescues individuals from their lost condition. (Thompson, pp. 127-128)

That’s exactly what I have understood all these years. I had to set aside Thompson and get back to the Stendahl article he cited as my first step in addressing immediate questions that come to mind. Didn’t Paul cry out in desperation in Romans 7 that he struggled helplessly against his body of sin? No, he didn’t — as Stendahl pointed out. Paul spoke of a body of “death” but not “sin”. But, but …. Okay, I’ll try to hit the highlights of the article. Many readers are no doubt already well familiar with it. A web search will point to many discussions about the article online. So I will try to focus on the points that I found salient.

It’s all Augustine’s and Luther’s fault

The quotes are from Stendahl’s article in the HTR and all highlighting and some formatting is my own:

Especially in Protestant Christianity – which, however, at this point has its roots in Augustine and in the piety of the Middle Ages – the Pauline awareness of sin has been interpreted in the light of Luther’s struggle with his conscience. (Stendahl, p. 200)