I grew up in a small city in eastern Ohio, right on the border with Pennsylvania, a tiny place called East Palestine. The story goes that back in the 19th century to escape higher taxes in their home states, a number of industrialists set up shop in the first town on the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad (later called the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago Railway). That’s how my little town became a base for the pottery industry from 1880 on into the 1960s. Border towns like Steubenville and East Liverpool also attracted the pottery manufacturers. Those cities used the Ohio River to move goods, while our little town relied on the Pennsylvania Railroad to take our wares to Chicago or Pittsburgh (and beyond).

A view to a kiln

My mother worked in one of those potteries. Many women did. As I recall, my dad’s mother and at least one of his sisters worked there too. On that side of the family, they still called it the pott’ry, following their English forebears. My mother didn’t. She grew up on a farm, and all her folk called it the pottery.

Once when I was very young, I visited my mom at work, and watched her as she affixed handles to cups. They were still soft and pale gray. She would quickly wipe them down with a damp sponge to remove any excess clay and to smooth out the surface.

“I’m getting them ready for the kiln,” she said. She pronounced it KILL, and so I was taken aback. They were going to be killed? She noticed my confusion and explained that it was a huge oven that baked the clay. And even though we spell it “k-i-l-n,” everyone there pronounced it kill.

Not only did everyone in the pottery call it the kill, but they used it as a marker. Only an outsider would get it wrong. Everyone on the inside knew the “right” way to pronounce it.

I worked in The Building

Many years later, I had a similar experience while working in the intelligence field. In those days, we were reluctant even to utter the words “National Security Agency” or even the letters “NSA.” We’d sometimes refer to it in public as “No Such Agency.” When my wife and I lived on Ft. Meade, we’d often use the euphemism The Building, as in the sentence: “I’m headed over to The Building.”

When we did speak of NSA, we never used the definite article. For example, we would send tapes “to NSA,” never “to the NSA.” So when James Bamford’s The Puzzle Palace came out in 1982, and he appeared on TV saying things about “the NSA,” I immediately doubted his credibility. I know it sounds silly, but it’s one of those clear linguistic markers that insiders know and take to heart.

Historical names

While pursuing my degree in history, I discovered some similar markers. For example, I noticed that professors of medieval history tend to pronounce Augustine’s name as uh-GUST-in, not AW-gus-teen. The unsure student adapts quickly — I found that saying it with the stress on the first syllable made me feel like a country bumpkin.

Similarly in Roman history, professors and their graduate assistants pronounced the Anglicized name of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) as POM-pee. As Merriam Webster says, it rhymes with swampy. If you pronounced it with the stress on the second syllable — pom-PAY — somebody would eventually tell you that you were confusing it with Pompeii, the city that Vesuvius destroyed in 79 CE.

Outright mistakes

You could argue that the above variations aren’t actually mistakes; they’re simply matters of preference. Just because the majority of people today pronounce the word “era” as if it rhymes with “terra,” I still cling to the old pronunciation, EER-a, as if it rhymes with “Indira.”

But some pronunciations are just plain wrong.

I recall in middle school barely paying attention to an oral book report in which a classmate kept talking about these terrible people I’d never heard of. Something about a girl being hidden in an attic. And there was this kind and heroic Dutch family, hiding Jews from the NAZZ-eyes. Whenever these NAZZ-eyes would show up, the Jewish family would run and hide. Then one day those NAZZ-eyes . . . Suddenly, I shouted out: “Nazis! She’s talkin’ about Nazis!” I can still remember the dirty looks I got that day.

Several years later, one of my ancient history professors told us that one easy way to tell whether somebody is a phony is if he or she mispronounces the name of the kingdom where Sumerians lived. Anyone who mispronounces Sumer as Sumeria, he explained, is a charlatan. “Sumeria” is a modern mistake that comes from the back-formation of the word Sumerian, or perhaps through confusion about the land of Samaria. Sumeria is just as wrong-headed and laughable as Egyptia (back-formed out of Egyptian).

He told us the Akkadians said “Šumer” (SHOO-mer). And while you can find the word Sumeria in popular literature, especially in books about ancient astronauts and alien abductions, real scholars don’t use it.

Unfortunately, I see that Sumeria has lately become more commonplace. In fact, I was recently listening to one of The Great Courses — Ancient Empires before Alexander — by Dr. Robert L. Dise Jr., when I heard this:

A thousand years after the dawn of civilization . . .

I nearly fell over. Has Sumeria gone mainstream?

Having fun with it

Naturally, we sometimes mispronounce words on purpose. A buddy of mine once told me that he used to joke around in restaurants. “How is the KWITCH-ee?” he once earnestly asked his waitress, while pointing to the quiche listed on the menu. Horrified, she bent down and whispered hoarsely in his ear, “It’s pronounced ‘KEESH’!” He smiled at her and whispered, “I know!”

Around our house, we always refer to I, Claudius as I, CLAV-divs, in honor of a friend who many years ago saw the cover of the Penguin novel I was reading and didn’t realize Roman U’s on monuments look like V’s.

“I, Clavdivs?” he asked.

I can’t tell you how happy it makes me to see that AbeBooks.com has a listing for I, Clavdivs and that somebody on iOffer is selling a copy of Clavdivs the God.

This sort of tomfoolery can backfire, of course, if you think somebody in a position of authority is making a joke, but isn’t. Before laughing uproariously, make sure whether your professor or your boss is really joking when he says POIG-nant. This kind of thing can get you in hot water . . . or so I’m told.

Five scrolls

Biblical studies has more than its fair share of obscure words from various ancient and modern languages, and if you haven’t had the luxury of taking courses at the university level, you many have never heard them pronounced. I once heard someone on a podcast pronounce Pentateuch as PEN-ta-toik, which I suppose isn’t too strange, if you were trying to pronounce a Greek word with German pronunciation rules. The host corrected the person right away, which is rather unusual, but welcome.

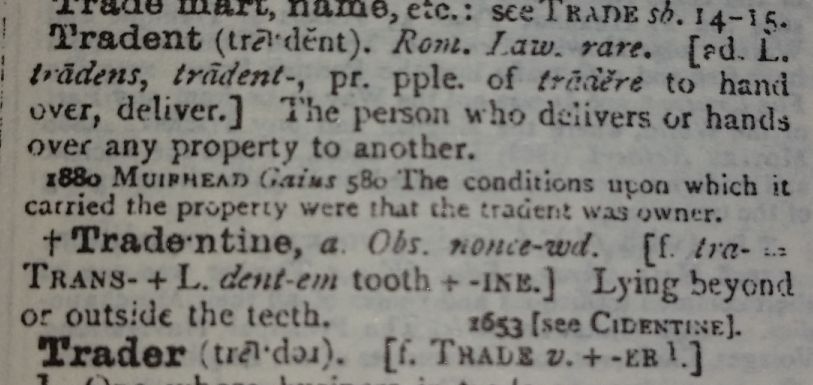

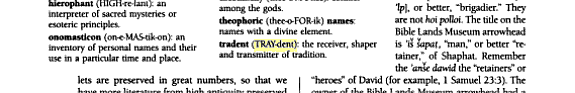

Sometimes the obscure words are merely rare, but still quite English, words. For example, I couldn’t find the word tradent in Merriam Webster’s Third New International Dictionary. I did, however, find it in my copy of the Oxford English Dictionary. Recently, while listing to a recorded book, the author/reader said TRA-dent with the “A” sound found in “cat.” Now, every professor I’d ever heard say this word pronounced it TRAY-dent, but I began to doubt myself. Bless the Brits for their wonderful OED.

Here you can plainly see that the “ei” diphthong found in word tradent is exactly the same as the one in the word trader. The word has a more specialized meaning in the study of oral history and oral tradition, but it has the same pronunciation. The Biblical Archaeology Society agrees. Here’s a snippet from Bible Review, Volumes 8-9, 1992 (snippet from Google Books).

In that same audio book, the author/reader pronounced the word recension as re-KEN-shun, which wouldn’t have been so painful if it hadn’t occurred four times in the same paragraph. For our purposes here, it doesn’t matter who the reader is. I don’t question the author/reader’s intelligence, nor does it directly affect his argument. But I can’t help but ask myself, “Doesn’t he ever talk to anyone who knows how to pronounce ‘recension’?” And: “Didn’t he ever take a class in which the professor said the word ‘recension’?”

The book is full of eccentric pronunciations, but, as I said, I don’t question his intelligence. However, I do suspect on some subjects he is book-learnt, and that can be worrisome, since it calls into question breadth of experience. By book-learnt, I mean that he appears to have read an impressive amount, but may have missed out on interaction with faculty and other students. You can try to make up for these shortfalls by listening to recorded lectures and interviews, but it isn’t easy.

The Erhman train wreck

One reader whose intelligence is completely out of the question is the person who read Bart Ehrman’s Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics. Here’s how the book starts:

Forgery and Counterforgery (Ehrman)

Yes, he really said puh-LEE-miks. It starts badly and spirals downward from there.

I won’t mention the reader’s name here, because in cases like this we really have to blame the director and the publishing house. No one this incompetent should be permitted near a microphone. Ehrman himself has probably never listened to it, or else it would have been pulled from the shelves. The book is riddled with bizarre inflections and flagrant mispronunciations. Even common Biblical names aren’t safe from this guy.

We can’t help but ask how a person reaches adulthood without knowing how to pronounce the word “mischievous.” But what’s most vexing is the unconscionable act of selecting a person who clearly has no interest in ancient history and saddling him with the job of reading such an important and well-written book. Where in the world did they find someone who cannot pronounce famous personal names like Herod or Josephus, or place names like Arimathea (which he pronounces a-rih-MATH-ee-uh)? Or whose vocabulary is so limited that he thinks the word bier (BIR) rhymes with fire (BYRE)?

Does it really matter?

I fully accept the notion that living languages evolve and that spoken language determines correct usage. On the other hand, I lament the change in some words because it impedes comprehension. For example, in one recent book I was listening to, the reader did not know the difference between the noun, prophecy (PROF-eh-see), and the verb, to prophesy (PROF-eh-sye), which surely must confuse listeners. I hope this is just a random aberration and not a trend in English.

On the other hand I’ve recently heard one reader use an eccentric pronunciation of Elisha. Instead of ee-LYE-shuh he said eh-LISH-uh. At first it sounds ugly, but it’s actually kind of useful to contrast it with Elijah (ee-LYE-juh), so there’s no ambiguity. Perhaps this variation, although likely borne of ignorance, may prove useful in the long run.

East Palestine rhymes with “East Palace-Teen”

I mentioned above that I grew up in a tiny Ohio town called East Palestine. For unknown reasons, everyone who lives there calls it “Pales-teen,” not “Pales-tine.” To be pedantic about it, most people there tend to pronounce “L” sounds in the middle of a word as “wuh,” so it sounds more like “POW-wes-teen.” But no matter what they call it, it’s correct. It’s a privilege of residency. If the majority of the inhabitants of Norfolk, Virginia, say “NAWR-fick,” then that’s what it is.

Of course, no Sumerians survive today to remind everyone that the name of their country was not “Sumeria,” so I guess it’s up to you and me.

“Pardon me. It’s . . . [ahem] . . . Sumer.”

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Why not. “Bayzhing” has.

Can’t help but mention here two instances that have the effect of a fingernail scratching on a blackboard (surely an antediluvian analogy) for me — “Revelations” for the Book of Revelation: seems to be quite common among even biblical scholars; is it really legit? & “prophesize” for the “prophesy”.

I can never forget a minister delivering a sermon on the origins and early history of the Passover (we were a Passover, not Easter, keeping church) with all his bombastic confidence making an utter fool of himself every time and several times he happened to referred to PolyCRATES. No scholar or public speaker should be allowed to utter a Greek name in public without a prior seal of approval from an undergraduate in ancient history.

At the same time I worry about some of my own head-pronunciations of a few regular names and technical terms that I have read so often — but only read. We can discuss questions with scholars online nowadays, but it’s still all reading. I had always pronounced Marcion in my head with a k (Μαρκίων) but not very long ago learned everyone else was apparently using a soft c or even referring to him as a Martian: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3_CyUnEadl4

I have just discovered that by typing in a name followed by “pronounce” or “pronunciation” in Google one gets a handy youtube guide. e.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nQ6UJHGcY8 for Irenaeus — another one that can mislead the book-learned and on-line discourser.

Earl Doherty must be commended for making pronunciations clear in his books.

It’s only by luck that I heard the name “Marcion” before I read it. I blame the Brits for transliterating it oddly to begin with.

LSeveral years later, one of my ancient history professors told us that one easy way to tell whether somebody is a phony is if he or she mispronounces the name of the kingdom where Sumerians lived. Anyone who mispronounces Sumer as Sumeria, he explained, is a charlatan.”

-At what point was Sumer ever a kingdom?

Also, mispronouncing “Lachish” is really easy.

E. asked, “At what point was Sumer ever a kingdom?”

You could start by asking Harriet Crawford, Senior Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, and Reader Emerita at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, UK.

Also, protip: nobody in the region pronounces it “Kraiymeeya”.

Isn’t it odd how for certain parts of the globe Americans often trip over ourselves trying to sound like natives — like, “Nicaragua” (nee-kuh-RAH-gwah) — while other places never get the same treatment — like “Moscow” (musk-VAH)?

It isn’t “MOSS cow?”

For the Anglicized version of Москва, I do prefer “MOSS-cow,” although some U.S. news outlets have started saying “MOSS-coh.”

http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1998/11/09/250856/index.htm

There’s another Ohio town near Athens named Chauncey but it is pronounced Chancy. I’m told that back in the Prohibition days, if it was mispronounced, it was assumed the person was a revenuer and given misinformation.

That brings back memories. When I attended Ohio U., I recall the announcers on local radio talking about “Chauncey and The Plains.”

Great post, Though it has made me feel dumb…lol

It is one thing to read these words but like a different world to hear some of them pronounced.

Two additions to the list:

Byzantine

Aegean

Some Brits say bih-ZAN-tyne, which sounds really odd to me.

http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/byzantine

I challenge any American not in the know to pronounce “Featherstonehaugh” correctly.

I’m pretty sure it’s pronounced “Smith.”

Nearly right – in the same sense that Ken Ham and Kent Hovind are nearly right about science.

Milan, New York is pronounced MIE-lun. Lima, Ohio is pronounced LIE-muh. There seems to have been a vogue for this sort of thing.

Funny how Palestine went the other way. There’s a North Lima, Ohio, near where I grew up, also with a long “i,” as in “lima beans.”

By the way, the citizens of Wooster, Ohio, never have to worry that newbies will call it “wor-CES-ter-shire.”

Tim, you forgot to mention my pronunciation of vorlage in a Bible Geek Listeners hangout you were in, which, as we all know, means “the position of a skier leaning forward from the ankles usually without lifting the heels from the skis”. That’s a classic example of “Book Learning Onlyism.”

Oh, and there are so many more. Your Vorlage reminds me of the Alan Alda character in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors who pronounces foliage as “foilage.”