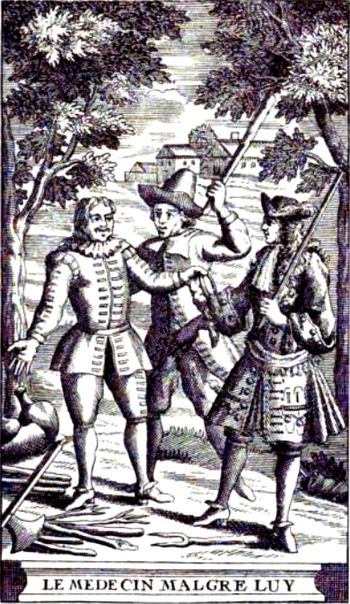

Today’s text comes from Molière’s play, Le Médecin malgré lui (The Doctor in Spite of Himself). We join in as Sganarelle, a poor, drunken woodcutter, posing as an eccentric but brilliant physician, pretends to diagnose Lucinde, the daughter of a wealthy couple. Her parents, Géronte and Jacqueline, along with their servant, Lucas, watch and comment as Sganarelle bamboozles them with a stream of nonsense. Sganarelle seeks to explain why Lucinde has lost the ability to speak.

Sganarelle: . . . But to come back to our reasoning. I hold that that interference with the action of the tongue is caused by certain humors, that, among ourselves we scientists call humors peccantes. Peccantes, it should be said — humors peccantes. Moreover, as the vapors formed by the exhalations of the influences which originate in the region of the affected area come, — that is to say — ah — do you understand Latin?

Géronte: Not a word.

Sga.: You don’t understand the Latin?

Ge.: No.

Sga.: Cabricias arci thuram catalamus singulariter nominative heac musa “la Muse” bonus, bonum, Deus Sanctus, estne oration latinas? Etiam “oui” Quare, “pourquoi?” Quia substantivo et adjectivum concordat in generi, numerum, et casus E —

Ge.: Ah, why didn’t I study Latin?

Lucas: Yes, it is so beautiful that I do not understand a word of it.

Sga.: Now, these vapors of which I talked, as they come to pass from the left side, where the liver is, to the right side where the heart is, find themselves at the lungs as we call it in Latin, armyan, having communication with the neck that we name in Greek by means of the venicava, that we call in Hebrew cubile, encounter in their way the aforesaid vapors, which fill the ventricles of the shoulder blades, and because the aforesaid vapors — pay close attention to my reasoning, I beg of you, — and because the aforesaid vapors have a certain malignity — listen carefully to that I conjure you —

Ge.: Yes.

Sga.: Have a certain malignity which is caused — attention, if you please —

Ge.: I am attending.

Sga.: Which is caused by the accretion of humors engendered in the concavity of the diaphragm, it comes about that these vapors. . . . ossidbandus nequeys, nequer, potarinum, quipsa, milus. Behold, this is exactly the cause of your daughter’s speechlessness.

Jac.: Ah, that’s well said, my man.

Ge.: No one could reason better, but there is one thing that has shocked me. It is the place of the liver and of the heart. It seems to me that you have placed them otherwise than as they are, that the heart is on the left side, and the liver on the right.

Sga.: Yes, certainly it used to be that way; but we have changed all that, and we now practice medicine by an entirely new method.

Ge.: That’s what I didn’t know, and I beg pardon for my ignorance.

Sga.: No harm done. You are not obliged to be as learned as we.

Sganarelle utters a line near the end which many of us learned in the French: “Nous avons changé tout cela.” It has become a sort of cliché for anyone sweeping away the old ways of doing things, replacing it with something new — anything new, often radically new, occasionally nonsensically new. Sometimes this new thing is so beautiful that we, like Lucas, don’t understand a word of it. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 8: Chris Keith, Post-Criteria Scholar? (2)”