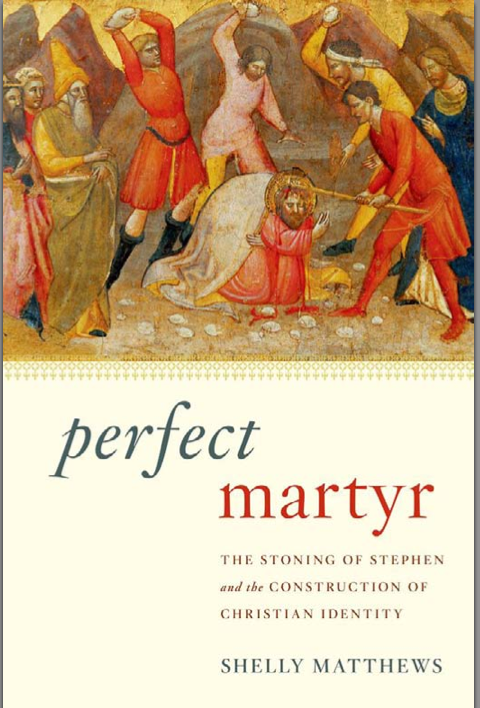

I was introduced to the work of Shelly Matthews through the Acts Seminar Report. She is one of the Seminar Fellows. I have since read — and enjoyed very much — her historical study Perfect Martyr: The Stoning of Stephen and the Construction of Christian Identity.

I was introduced to the work of Shelly Matthews through the Acts Seminar Report. She is one of the Seminar Fellows. I have since read — and enjoyed very much — her historical study Perfect Martyr: The Stoning of Stephen and the Construction of Christian Identity.

Shelly Matthews is one of the few theologians I have encountered who demonstrably understands the nature of history and how it works and how to apply historical-critical questions to the evidence. She is a postmodernist (and I’m not) but I won’t hold that against her. At least she understands and applies postmodernist principles correctly — unlike some other theologians who miss the point entirely and resort to trying to uncover “approximations” of “what really happened” behind the fictional (and ideological) narratives in the Gospels and Acts.

Matthews is critical of the way scholars have with near unanimity assumed that the story of Stephen’s martyrdom in Acts is based on some form of bedrock historical event:

- How else to explain the sudden propulsion of Jesus followers beyond the limits of Palestine?

- (Recall that the Acts story tells us it was the death of Stephen that instigated the wider persecution of the “church”, and persecution led to the scattering of the believers, and that scattering led to the proclamation of the message beyond Judea.)

- How else to explain the conversion of Paul?

- (Recall that Paul — originally “Saul” — was one of those persecutors and it was his “Damascus Road” experience that brought him to heel and turned him from persecutor to missionary.)

Those are the twin (prima facie) arguments that have assured scholars that the Stephen event is historical ever since they were made explicit in the nineteenth century by Eduard Zeller (son-in-law of F. Baur).

But let’s save the discussion of method and criteria of historicity till last this time (or maybe a follow up post). To begin with we will set out the grounds for questioning whether the Stephen narrative in Acts owes anything to some historical “core” event. The question of the historicity of Stephen’s martyrdom is not the primary theme or interest of Shelly Matthew’s study (as its title indicates) but she does address it as part of her larger discussion on historical-critical inquiry and the way scholars have culturally fallen under the spell of the fundamental narrative outline and ideology of Acts. (Her discussion could equally well apply to the question of the historicity of Jesus but I think we need to wait for scholars to come to grips more generally with critical and methodological questions about Stephen before taking that step.)

External evidence

Outside of Acts there is not a whisper of awareness of the martyrdom of Stephen until Irenaeus talks about it around 180 CE. And Irenaeus is clearly using Acts itself as his source. (Recall, too, that the Acts Seminar has concluded that Acts itself was written in the second century.)

Paul mentions in his letters several persons who were part of his life and that appear in Acts but he nowhere indicates that he ever owed his conversion to the events initiated by the martyrdom of Stephen — a martyrdom that he reportedly witnessed as an accomplice.

Clement of Rome and Polycarp wrote of Christian martyrs but appear to have never heard of Stephen.

If Stephen’s martyrdom had indeed been the first, and if indeed it had been the spark that initiated such a significant train of events as the expansion of Christianity and the conversion of an accessory to Stephen’s lynch mob, Paul, this silence is indeed unexpected and does cry out for an explanation.

Further, the later account of the martyrdom of James in Hegesippus (known from Josephus) is almost the same story as the martyrdom of Stephen. (Robert Price similarly refers to other scholars who have also noted the way the Stephen story is a variant of the martyrdom of James the Just.) So what is going on here? Matthews comments:

[T]his companion story suggests that while the motifs concerning the way the first martyr dies are crucial to the construction of group identity for early Christians, the precise identity of the first martyr is fungible. (p. 18)

Internal clues

Time for a little redaction criticism. The idea is that if we peel away what Luke added to his source then we are left with nothing but the source and the source is for some uncertain reason understood to be an account of “the historical event”. After outlining what scholars generally take to be “core” data sifted from Luke’s supposed “redactions”, Matthews alerts us to the arbitrary nature of the entire exercise:

Part of the difficulty with this barebones sketch of what happened (martyrdom) to whom (Stephen), by whom (a mob of riotous Jews) for a certain reason (religious disagreement centering around temple and torah), as has been quite persuasively argued by Todd Penner, lies in the fact that upon careful scrutiny each decision about what is kernel and what is chaff seems in the end arbitrary. This is not to deny the existence of sources for Luke but to suggest the impossibility of pinpointing them. (p. 19)

We also have the most happy coincidence that the name of the first martyr, Stephen, means “Crown” — the very reward for those who die for Christ. Given Luke’s love of symbolic names we may well be suspicious that this character is another construction of his — the paradigm of the Christian martyr. Or suppose Luke saw the name, Stephen, in a source. How could we know if Luke was not inspired to write a story of martyrdom as a result of his being attracted by the potential meaning of the name?

Ancient historians (and novelists) prided themselves on their ability to convey stories with touches of verisimilitude. Accordingly there can be no real way for us to sift such a narrative of theirs between “core historical events” on one side and “creative embellishments” on the other.

There are other internal clues that are not directly addressed by Shelly Matthews as such.

One of these is an absurdity singled out by Robert M. Price:

Luke’s reduction of the Jewish Sanhedrin to a howling lynch mob is not to be dignified with learned discussion. (The Amazing Colossal Apostle, p. 2)

Verisimilitude indeed for an anti-Semitic author and audience — a bigotry more typically found in the second century than the first.

Another detail commonly noticed is the contradiction found following Stephen’s stoning: the church as a whole being is so severely persecuted that it must scatter beyond to new territory, yet the twelve leaders remain curiously untouched and able to continue unmolested in Jerusalem. We may well ask, Did Stephen’s death really spark a wider persecution and scattering of the church or didn’t it?

If Luke did create Stephen and his martyrdom, why did he do so? How does Stephen function rhetorically in the narrative of Acts?

Here we edge closer to Shelly Matthew’s special interest. She spells out in detail the various ways in which Stephen is such a perfect rhetorical fit in the larger narrative. I am sure many readers will have sensed some of these points for themselves as they have pondered on the text.

Stephen’s “Rhetorical Fit”

Stephen stands as a pivot or gateway between the time of Jesus and the Jerusalem apostles and the broader mission of the church to the Gentiles led by Paul.

- He emerges in the midst of a conflict between two Jewish groups, Hebrews and Hellenists; compare Paul being at the centre of conflict between Jewish and Gentile believers.

- Just as the Jerusalem apostles were confronted by the temple leaders and as Paul faced hostile synagogues, Stephen first faces controversy in the synagogue and is subsequently tried by the Sanhedrin and high priest.

- The seven names in the list in which he first appears (Acts 6:5) conform to the larger plot-line of Acts: beginning with Stephen to the Greek speaking Jews and concluding with the evangelization of Gentiles at Antioch.

- The opponents of Stephen come from far and wide: Cyrenians, Alexandrians, and of those of Cilicia and Asia. The first in this list can be either Libyans or “Libertines”. Either this extends the geographic extent of his opponents or signifies that it crossed class boundaries as well. Compare Paul facing the opposition of peoples as far as “the ends of the earth”.

- Before the death of Stephen the history of the church centred upon Jerusalem; following his death we follow the action into Judea, Samaria and the “ends of the earth”.

- His death marked the beginning of the fulfilment of Jesus’ prophecy (1:8) that the disciples were to spread out through Samaria and the rest of the world; as a direct consequence of his death persecution fanned to the rest of the church; and that led to the scattering of the believers; and that in turn led to the wider proclamation of the gospel. After Stephen we move out from Jerusalem and find Philip preaching in Samaria, Paul being converted, Peter on a mission into Lydda, Joppa and Caesarea, and unnamed disciples converting people in Antioch — where the term Christian was coined to describe them.

- One vital function of the Stephen episode is the way it serves to establish the clear distinction between Jews and Christians.

- After the death of Stephen, the use of hoi Ioudaioi increases dramatically, becoming Acts’ preferred term of vilification for those who persecute and/or desire the persecution of Jesus followers (e.g., 9.23, 12.3, 12.11, 13.50, 14.5, 14.19, 18.12, 20.3, 20.19, 23.12, 25.24, 26.21). Concurrent with the increase in negative employment of the phrase hoi Ioudaioi in Acts after the Stephen episode is the abrupt cessation of sympathetic depictions of Jews as ho laos —the people of God. In the Jerusalem chapters, ho laos is portrayed positively, as open to the messengers of the Way. The people are convinced by the apostles and serve to protect them from a malicious leadership (e.g., 4.17, 4.21, 5.13, 5.26). However, once they are stirred up against Stephen in 6.12, “the people” lose their receptivity and act only with hostility toward the apostles. Thus, as Augustin George notes, after the death of Stephen, “the Jews,” are no longer “the people” of God. Their agency in the death of Stephen is integral to the making of hoi Ioudaioi . (pp. 67-68, my bolding)

- Stephen is in the same line of persecuted prophets as was Jesus, and as began with the martyrdom of Zechariah. In Luke 11 Jesus made Zechariah’s role (the one killed between the altar and the temple) paradigmatic.

- Stephen also fulfills the Deuteronomic pattern — that is, Israel kills the prophets and then suffers as a consequence — just as do Jesus before him and Paul after him.

- Like Jesus when facing his own execution, Stephen, modeling Jesus’ own death:

- speaks before the Sanhedrin

- speaks of the eschatological Son of Man at the right hand of God

- commends his spirit to the Lord at the moment of his death

- Moreover, just as Jesus prefigures Stephen, so Stephen prefigures Paul:

- note how Paul is explicitly linked to Stephen twice, once at his martyrdom and again in his speech from the temple steps.

- Stephen also functions to undermine the Jewish juridical process, an important theme for Luke who more generally seeks to show respect for Roman authorities while denigrating the Jewish ones as barbaric by contrast.

Forgive them, Father . . .

Absent from the above list is the notice that Stephen repeated Jesus’ famous words calling for forgiveness upon the Jews. Shelly Matthews chooses to devote the final chapter to a discussion of this detail. It is not as innocent or noble a prayer as the author wants us to believe.

Matthew’s interprets the prayer as ultimately serving a most pernicious function. It sets Christians apart as the ultimate in godly perfection, all-merciful and gracious even towards enemies. That is, it sets them apart from the Jews who are depicted as hard-hearted, implacable, without excuse any more (they had since learned that Jesus was resurrected and seen the signs of the miracles, so they were really without excuse by now), and incapable of being forgiven. Forgiveness of the Jews requires the repentance of the Jews. That message has been made clear up till now in Acts. While Luke places such a perfect prayer for a perfect saint in the mouth of the ideal Christian martyr, in his narrative presentation he leaves no room for forgiveness (or repentance) of the Jews. They have closed their ears to Stephen and want him dead when he proclaims his vision of Jesus Christ in heaven. There is a clear disconnect between the way the merciful prayer epitomizes Christians as saintly and the way the Jews are portrayed as wicked killers who even hate the very thought of what is required to be forgiven.

The prayer has served to entrench respective stereotypes of Christians and Jews, or more specifically, it has served to draw a sharp distinction between morally superior Christians and degenerate, murderous Jews.

So Stephen’s prayer does serve one of Luke’s core ideological agendas, though not a particularly noble one by our standards.

Is this conclusion justified?

So we have good reasons for questioning whether Luke based his narrative on a real event. We certainly see very good reasons why he might have wanted to create the scene just the way it appears. It very happily fulfills several rhetorical and ideological agendas of the author.

Was it coincidentally historical, too?

In a follow up post I’ll discuss Shelly Matthew’s postmodernist historiographical approach and historical critical method more generally. We will see how both open up entirely new insights into the nature of what biblical scholars have long considered their “primary evidence” for Christian origins and also into how genuine historical criticism, consistently applied, can expose the ideological and cultural assumptions that currently control their interpretations and assumptions.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Small biblioblogging world. Shelly Matthews worked at Furman for many years. I had a brief discussion or two with her in the lunch room, and was at one of her Christmas partiesyears ago. I’ve skimmed her book, but you summed it up neatly and concisely..

Another clue-in that the Martyrdom of St Stephen is fictitious is that Luke has Stephen start a speech that Paul completes in Pisidian Antioch, as Kenneth Humphries has noted over at Jesus Never Existed, concerning Paul’s sermon to the assembled synagogue in Pisidian Antioch:

The same comment is found in Richard Pervo’s “Dating Acts”:

To avoid oversimplification it is interesting to see how the two speeches do compare:

Stephen: Acts 7

Paul: Acts 13

3and said unto him, Get thee out of thy land, and from thy kindred, and come into the land which I shall show thee.

4 Then came he out of the land of the Chaldaeans, and dwelt in Haran: and from thence, when his father was dead, God removed him into this land, wherein ye now dwell:

5 and he gave him none inheritance in it, no, not so much as to set his foot on: and he promised that he would give it to him in possession, and to his seed after him, when as yet he had no child.

6 And God spake on this wise, that his seed should sojourn in a strange land, and that they should bring them into bondage, and treat them ill, four hundred years.

7 And the nation to which they shall be in bondage will I judge, said God: and after that shall they come forth, and serve me in this place.

8 And he gave him the covenant of circumcision: and so Abraham begat Isaac, and circumcised him the eighth day; and Isaac begat Jacob, and Jacob the twelve patriarchs.

9 And the patriarchs, moved with jealousy against Joseph, sold him into Egypt: and God was with him,

10 and delivered him out of all his afflictions, and gave him favor and wisdom before Pharaoh king of Egypt; and he made him governor over Egypt and all his house.

11 Now there came a famine over all Egypt and Canaan, and great affliction: and our fathers found no sustenance.

12 But when Jacob heard that there was grain in Egypt, he sent forth our fathers the first time.

13 And at the second time Joseph was made known to his brethren; and Joseph’s race became manifest unto Pharaoh.

14 And Joseph sent, and called to him Jacob his father, and all his kindred, threescore and fifteen souls.

15 And Jacob went down into Egypt; and he died, himself and our fathers;

16 and they were carried over unto Shechem, and laid in the tomb that Abraham bought for a price in silver of the sons of Hamor in Shechem.

17 But as the time of the promise drew nigh which God vouchsafed unto Abraham, the people grew and multiplied in Egypt,

18 till there arose another king over Egypt, who knew not Joseph.

19 The same dealt craftily with our race, and ill-treated our fathers, that they should cast out their babes to the end they might not live.

20 At which season Moses was born, and was exceeding fair; and he was nourished three months in his father’s house.

21 and when he was cast out, Pharaoh’s daughter took him up, and nourished him for her own son.

22 And Moses was instructed in all the wisdom of the Egyptians; and he was mighty in his words and works.

23 But when he was well-nigh forty years old, it came into his heart to visit his brethren the children of Israel.

24 And seeing one of them suffer wrong, he defended him, and avenged him that was oppressed, smiting the Egyptian:

25 and he supposed that his brethren understood that God by his hand was giving them deliverance; but they understood not.

26 And the day following he appeared unto them as they strove, and would have set them at one again, saying, Sirs, ye are brethren; why do ye wrong one to another?

27 But he that did his neighbor wrong thrust him away, saying, Who made thee a ruler and a judge over us?

28 Wouldest thou kill me, as thou killedst the Egyptian yesterday?

29 And Moses fled at this saying, and became a sojourner in the land of Midian, where he begat two sons.

30 And when forty years were fulfilled, an angel appeared to him in the wilderness of Mount Sinai, in a flame of fire in a bush.

31 And when Moses saw it, he wondered at the sight: and as he drew near to behold, there came a voice of the Lord,

32 I am the God of thy fathers, the God of Abraham, and of Isaac, and of Jacob. And Moses trembled, and durst not behold.

33 And the Lord said unto him, Loose the shoes from thy feet: for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground.

34 I have surely seen the affliction of my people that is in Egypt, and have heard their groaning, and I am come down to deliver them: and now come, I will send thee into Egypt.

35 This Moses whom they refused, saying, Who made thee a ruler and a judge? him hath God sent to be both a ruler and a deliverer with the hand of the angel that appeared to him in the bush.

37 “This is that Moses who said to the children of Israel, ‘The Lord your God will raise up for you a Prophet like me from your brethren. Him you shall hear.’

38 “This is he who was in the congregation in the wilderness with the Angel who spoke to him on Mount Sinai, and with our fathers, the one who received the living oracles to give to us, 39 whom our fathers would not obey, but rejected. And in their hearts they turned back to Egypt, 40 saying to Aaron, ‘Make us gods to go before us; as for this Moses who brought us out of the land of Egypt, we do not know what has become of him.’ 41 And they made a calf in those days, offered sacrifices to the idol, and rejoiced in the works of their own hands. 42 Then God turned and gave them up to worship the host of heaven, as it is written in the book of the Prophets:

‘Did you offer Me slaughtered animals and sacrifices during forty years in the wilderness,

O house of Israel?

43 You also took up the tabernacle of Moloch,

And the star of your god Remphan,

Images which you made to worship;

And I will carry you away beyond Babylon.’

44 “Our fathers had the tabernacle of witness in the wilderness, as He appointed, instructing Moses to make it according to the pattern that he had seen,

46 who found favor in the sight of God, and asked to find a habitation for the God of Jacob.

47 But Solomon built him a house.

48 Howbeit the Most High dwelleth not in houses made with hands; as saith the prophet,

49 The heaven is my throne, And the earth the footstool of my feet: What manner of house will ye build me? saith the Lord: Or what is the place of my rest?

50 Did not my hand make all these things?He raised up for them David as king, to whom also He gave testimony and said, ‘I have found David[c] the son of Jesse, a man after My own heart, who will do all My will.’

24 after John had first preached, before His coming, the baptism of repentance to all the people of Israel. 25 And as John was finishing his course, he said, ‘Who do you think I am? I am not He. But behold, there comes One after me, the sandals of whose feet I am not worthy to loose.’

26 “Men and brethren, sons of the family of Abraham, and those among you who fear God, to you the word of this salvation has been sent. 27 For those who dwell in Jerusalem, and their rulers, because they did not know Him, nor even the voices of the Prophets which are read every Sabbath, have fulfilled them in condemning Him

.28 And though they found no cause for death in Him, they asked Pilate that He should be put to death.

29 Now when they had fulfilled all that was written concerning Him, they took Him down from the tree and laid Him in a tomb.

30 But God raised Him from the dead.

31 He was seen for many days by those who came up with Him from Galilee to Jerusalem, who are His witnesses to the people. 32 And we declare to you glad tidings—that promise which was made to the fathers. 33 God has fulfilled this for us their children, in that He has raised up Jesus. As it is also written in the second Psalm:

‘You are My Son,Today I have begotten You.’

34 And that He raised Him from the dead, no more to return to corruption, He has spoken thus:

‘I will give you the sure mercies of David.’

35 Therefore He also says in another Psalm:

‘You will not allow Your Holy One to see corruption.’

36 “For David, after he had served his own generation by the will of God, fell asleep, was buried with his fathers, and saw corruption; 37 but He whom God raised up saw no corruption. 38 Therefore let it be known to you, brethren, that through this Man is preached to you the forgiveness of sins; 39 and by Him everyone who believes is justified from all things from which you could not be justified by the law of Moses.

52 Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? and they killed them that showed before of the coming of the Righteous One; of whom ye have now become betrayers and murderers; . .

Yes, thank you! I’m glad it’s not just an armchair scholar who’s made a name for himself has figured this out. Seeing the two anti-Judaic lectures side-by-side really does demonstrate, to me at least, that the two came from the original common speech. Just exactly who that speech was originally attributed to is quite the mystery, and Luke hasn’t told us.

“If Luke did create Stephen and his martyrdom, why did he do so? How does Stephen function rhetorically in the narrative of Acts?… note how Paul is explicitly linked to Stephen twice, once at his martyrdom and again in his speech from the temple steps.”

I sometimes wonder whether the materials from which the author of Acts created his story were the various versions of Paul that were circulating among mid-second century Christians. In this scenario the John who is repeatedly paired with Peter early in Acts (3:1; 3:11; 4:13; 4:18; 8:14) would be a sanitized nod to the Johannine(/Apellean?) version of Paul (see my post Was Paul the Beloved Disciple?). And if so, the martyrdom of Stephen, the “crowned one,” could reflect how Johannine/Apellean Christians believed their Beloved Disciple had ended his days. I am just speculating, of course, for the extant record doesn’t give us information about that part of their belief. But the promise to “Nathanael” in Jn. 1:51 (that he will “see the heavens opened and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man”) never gets fulfilled in the Fourth Gospel. So I have wondered whether the portrayal of the crowned one in Acts 7:56 who, as he dies, sees “the heavens opened and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God” could reflect Johannine belief about its fulfillment.

It is generally held that Paul really only comes into the Acts story in chapter 9 (though he get a fleeting reference as Saul in 8:1) and that he is the central character only from that point on. But various characters in the early chapters (Peter’s companion John, Stephen, and Simon of Samaria) may be reworked and sanitized Pauline material. If so, the whole of Acts in effect is about one man. My vote for who the original figure was goes to Simon.

The more complex and fluent the “rhetorical fittingness” of the Stephen episode within the larger narrative the less likely, I would think, do its details owe anything to a reality that fortuitously lent itself to such a literary and thematic fluency and the more likely they originate in the creative mind of the author.

Yes, for the reasons you mention the Stephen episode could have been the creation in toto of the author of Acts. But since there is a good chance that for most of his work he creatively used sources (the Pauline letters), he may have used a source too for the crowned one’s martyrdom. And many scholars are even more convinced that is the case for the crowned one’s speech. It is just too unlike the typical speeches the author puts in the mouths of Peter and Paul throughout Acts.

Just to be clear, I don’t think the episode reflects a particular historical martyrdom. I think it may reflect (and rework) the belief of a particular second century community about a purported martyrdom.

Another possible provenance for the account of the crowned one’s martyrdom could be the second century Helenians. Celsus said the Helenians reverenced as their teacher Helen—the Helen who, according to Simon, was the Wisdom of God and his Holy Spirit. In the Acts of the Apostles the crowned one is selected when “the HELLENISTS complained against the Hebrews because their widows were being neglected in the daily distribution” (6:1, my caps). He was selected from among those “filled with wisdom and the Spirit” (6:3) and his opponents “could not withstand the wisdom and the Spirit with which he spoke” (6:10). He reproaches the Jews with: “You always oppose the Holy Spirit.” And when he sees the heavens opened he is “filled with the Holy Spirit.” These may be clues to the provenance .