Well I really blew it in the eyes of some readers when I posted on Scott Atran’s response to Sam Harris’s public statements about Islam and its relationship to terrorism. Let’s see if I can learn anything and do better with my presentation of Atran’s response to similar claims by Richard Dawkins.

Well I really blew it in the eyes of some readers when I posted on Scott Atran’s response to Sam Harris’s public statements about Islam and its relationship to terrorism. Let’s see if I can learn anything and do better with my presentation of Atran’s response to similar claims by Richard Dawkins.

Maybe if I begin by quoting the following words of Scott Atran I will be off to a better start:

I certainly don’t criticize [Harris and Dawkins] and other scientifically minded new atheists for wanting to rid the world of dogmatically held beliefs that are vapid, barbarous, anachronistic, and wrong. I object to their manner of combat, which is often shrill, scientifically baseless, psychologically uninformed, politically naïve, and counterproductive for goals we share. (Talking to the Enemy, p. 427, my bolded emphasis as throughout)

Now I really have liked and gained so much from Richard Dawkins’ writings. Some of his ideas I have had reservations about, and a few I cannot agree with at all given my other studies and experiences on the topics. But I like his efforts to promote rationality in public discourse. And I especially like his educational works on evolution. For all of that, though it is a hard to accept, the cruel fact is that not many of us are perfect in every way.

Sometimes a prominent public figure speaks about a field that is outside his or her area of expertise. Those who pull this off the most successfully are comedians. The light-heartedness of their grasp of issues pays off. No-one studies their jokes in order to educate themselves about the fundamental realities of how the world really works. (I know, many jokes are “funny because they’re true” but we don’t learn what’s true from them.)

But when a public figure whom I admire in many ways says something publicly, as if it were fact, that I know is contradicted by the publicly available research data itself, and that is even dangerous because it can fan a wider ignorance and lend support to mischief and harmful actions, then it hurts. What’s more, because there are a few areas where I do have more knowledge, being more widely read in the relevant areas, I do feel some sense of responsibility to try to speak up in some way when I hear a prominent person influencing others with misinformation. What I would like to achieve if at all possible is that a few others might for themselves explore the works, the information, the research, that belies many of the claims of Dawkins and Harris about the link between Islam and terrorism.

The first of the “new atheist” publications about religion that I read was Dan Dennett’s Breaking the Spell. It was quite different in approach from Harris’s, Hitchens’ and Dawkins’s contributions, so I was interested to see that Atran likewise does not have the same criticism of Dan Dennett as he has of Harris’s and Dawkins’s books:

Dan Dennett treats the science of religion in a serious way. Dan believes that universal education should include instruction in the history of religion and a survey of contemporary religious beliefs. Once out in the open for everyone to examine, science can better beat religion in open competition. My own guess is that it won’t work out that way, any more than logic winning out over passion or perfume in the competition for a mate. (p. 525)

So I hope no-one thinks I’m “Dawkins bashing”. It is possible to have a high regard for someone yet disagree with them profoundly on particular viewpoints and endeavour to appeal to verifiable facts to make one’s point rather than accusing others of dishonesty.

Here is a passage from Dawkins’ The God Delusion that Atran finds problematic — he actually describes it as “fantasy”. So let’s read Dawkins’ words and then calmly and rationally consider Atran’s disagreement with them:

Suicide bombers do what they do because they really believe what they were taught in their religious schools; that duty to God exceeds all other priorities, and that martyrdom in his service will be rewarded in the gardens of Paradise. And they were taught that lesson not necessarily by extremist fanatics but by decent, gentle, mainstream religious instructors, who lined them up in their madrasahs, sitting in rows, rhythmically nodding their innocent little heads up and down while they learned every word of the holy book like demented parrots.

Dawkins is expressing here a common view. Many people believe that Islam is to blame for terrorist attacks because it teaches both violence and the necessity of submission to teachings and holy texts encouraging acts of violence. On the surface of it I would have thought this to be a very superficial “analysis” that would be rejected by most informed readers after a moment’s reflection. But I am slowly and painfully being made aware that not everyone is well or reliably informed about

- how religion works, that is, from advances in research in recent years (even ex-religi0us people — I know I have learned a lot from professional studies about my own past experiences);

- the nature and history of Islam (I am astonished at the number of times I hear people say they understand the religion because they have read the Koran!);

- the geo-political, social, cultural, ethnic, economic and historical backgrounds to the countries and peoples producing most terrorists;

- the historic social and communications revolution we are entering now in the twenty-first century, accompanied by mass relocations of peoples, and the impacts these are already having on the breakdown of community cultural forces and especially youth culture.

But the fallacy of Richard Dawkins’ claim here is so fundamental that it requires no knowledge in any of these areas. If there is really any truth to Dawkins’ explanation for suicide terrorism then it is truly most astonishing that so few Muslims who have been taught in religious schools apparently “really believe” what they were taught there. If killing innocent civilians is an indicator that they really believe their teaching then it is clear that so very few practice what they supposedly learned or even approve of others doing so.

Now Atran’s book, Talking to the Enemy, discusses in depth his personal encounters and the current scholarly research into suicide bombers and would-be suicide terrorists. This research is undertaken by anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists and political scientists — that is, by professionals with the relevant training and skills who publish their findings in the peer-reviewed scholarly journals and other media. One would expect someone from outside these fields to take some notice of what they have learned about suicide bombers. Other scholars who concentrate their studies on modern terrorism and that I have read — Riaz Hassan and John Esposito — have presented research data that is consistent with the research of Atran and draw similar conclusions about the nature of the links between Islam and terrorism. (I have more scholarly works beside me to read on this topic so I am open to learning more.)

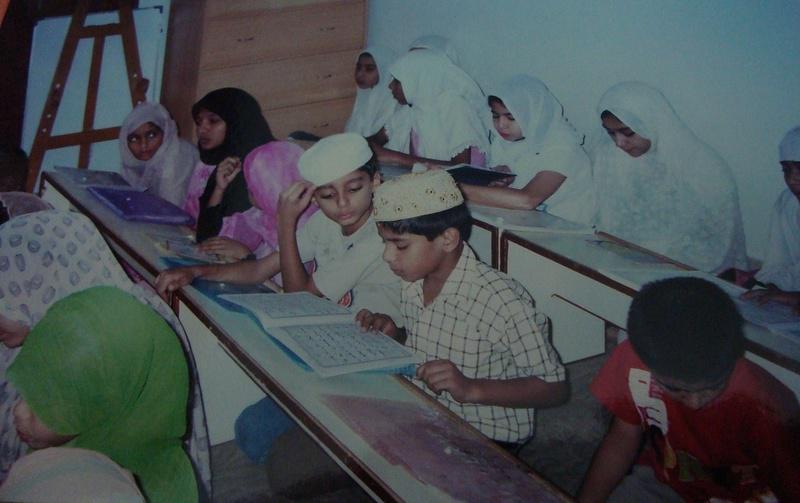

The role of religious schools

![]()

Atran writes towards the end of his book (after discussing earlier in depth interviews with and data about suicide bombers and would-be suicide bombers):

Atran writes towards the end of his book (after discussing earlier in depth interviews with and data about suicide bombers and would-be suicide bombers):

In fact, none of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers or thirty-odd Madrid train-bomb conspirators attended a madrassah, and the one July 2005 London Underground suicide bomber, Shehzad Tanweer, who did attend a madrassah in Pakistan, did so very briefly. Only a relatively small minority even had a boyhood religious education, including the 9/11 plotters.

“Decent, gentle” mainstream religious instructors generally do not teach the duty to suicide bomb, and even the overwhelming majority of Salafi (Muslim “fundamentalist”) instructors vehemently oppose it, as do most Wahabis, who generally profess loyalty to the state. (p. 418)

Yes, there are madrassahs that shun secular education and encourage rote learning as Dawkins portrays, But . . .

terrorist groups rarely draw from their students because these lack the needed social, linguistic, and technical skills to successfully carry out operations in hostile territory.

Pakistan and Indonesia have both the greatest numbers of madrassahs and jihadi groups. But less than 1% of those madrassahs are associated with jihadi groups. And those that are so associated with terrorist organizations (Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Tayibah and Indonesia’s Jemaah Islamiyah) also offer science and technical education. The only ones in those schools who might be trained in activities useful for terrorism are those who are the brightest and top of their classes.

As people who have gone through these schools have made clear to me, just parroting the Koran is not the kind of linguistic skill that gets you a top role in the jihad. (p. 418)

This post is not a diatribe against Dawkins; it is an attempt to say that there is information and facts on this topic that are being bypassed in much of the public discourse. This information deserves to be noticed.

Praising scientific works then chucking their main findings

Dawkins cites and even praises a number of serious scientific works on the cognitive and evolutionary origins of religious belief, but simply chucks their main findings when he claims, for reasons only Freud would know, that grown people seek religion because they miss their fathers.

Earlier in life, children allegedly believe because “natural selection builds child’s brains with a tendency to believe whatever their parents and tribal leaders tell them.” Children, like “computers, do what they are told: they slavishly obey any instructions given them in their own programming language.“

Atran finds this section (from pages 172 to 190 of The God Delusion) likewise problematic, especially since Dawkins also has argued that jihadis are also essentially “robotic learners” (see the earlier quotation above).

What’s the scientific evidence presented for Dawkins’s own science fiction that children or jihadis are robotic learners? None.

Now, it’s almost the sworn duty of any scientist to cite any serious counterevidence to one’s own claims. In this case, counterevidence is overwhelming.* (p. 419)

* See, for example, Race in the Making.

The slavish mind

Just as Dawkins is repeating pop fiction when making statements about how children learn, so he is repeating uninformed wives tales or urban myths about jihadi terrorists being somehow brainwashed by religion to become killers.

According to Atran, Dawkins’ statement about how children learn contradicts what child psychologists know; and I myself can concur: I once majored in child educational psychology and have taught young children and I know that if Dawkins’ summary had an ounce of validity to it there would not need to be any courses in child educational psychology. And I know that so much has been discovered since my days of formal study.

Dawkin’s implication is that this is how we learn religion, and that we somehow never outgrow our childish ways of thinking. Religious belief is thought to be some sort of childlike way of thinking. In reality, however, abundant research shows that that is not how people do take on or cling to religious beliefs.

And it is certainly not how terrorists become committed to acts of murder. That is a much more complex process. (If we misunderstand human nature and how people come to do the things they do we risk effecting policies that will only worsen the problems we are trying to solve.)

Dawkins is so convinced of the “robotic mind” model of how children learn that, like Plato, he expresses some concern about the benefits of fairy tales being told to children. Atran wryly comments that Dawkins’ own childhood readings of frogs turning into princes appear not to have damaged his scientific mind. Indeed, children do know the difference between fantasy tales and the real world. Atran quotes C. S. Lewis:

I never expected the real world to be like fairy tales. I think that I did expect to be like the school stories. The fantasies did not deceive me; the school stories did.

The fairy tale meme

The same naive view of how people learn may lie at the basis of his view that ideas are like “memes”:

Even a superficial examination of studies and experiments in human cognition and reasoning demonstrates unequivocally that ideas do not “invade” and occupy minds, or spread from mind to mind like self-replicating viruses or genes, as Dawkins and company maintain. However simple and appealing may be the notion of an ideology as a self-replicating high-fidelity “meme,” psychologically that’s pretty baseless and unrelated to how the mind actually works — almost as distant from reality as the claim that religion itself is the greater cause of human group violence. (p. 476)

Moving on from Dawkins now

Let’s leave Dawkins’ views of how people learn and become obsessed with crazy and destructive ideas. A full discussion is beyond the possibility of a blog post. But here’s another thought from Talking to the Enemy worth keeping in mind:

Mundane beliefs can be undermined by reasoned argument and empirical evidence. Not so religious beliefs, which are rationally inscrutable and immune to falsification: You can’t possibly disprove that God is all-seeing or show why he’s not more likely to see just 537 things at once.

Experiments suggest that once people sincerely commit to religious belief, attempts to undermine those beliefs through reason and evidence can stimulate believers to actually strengthen their beliefs.

For the believer, a failed prophecy may just mean there is more learning to do and commitment to make. (p. 448, my bolding)

But this is not a reason to give up.

Reason’s greatest challenge — in politics, ethics, or everyday life — is to gain knowledge and leverage over unreason: to cope with it, compete with it, and perhaps channel it; not to fruitlessly try to annihilate it by reasoning it away. (p. 426)

So what does make a terrorist?

So if funneling Islamic teaching into a sponge-like brain does not cause people to become terrorists, what does? I do not plan to outline all the research here, but I will cite a few conclusions from three scholars who do specialize in this field about the link between Islam and terrorism.

John Esposito & Dalia Mogahed: (John Esposito has produced a new book I have not yet read, title Islamophobia. Here is an interview in which he responds to the question: “In your latest book, Islamophobia, you mention Western media as the biggest cause for the misunderstanding of Islam and equating it to terrorism, but what role did Arab media and dictatorships play in maintaining that misconception?”. The following is from his earlier work:

The religious language and symbolism that terrorists use tend to place religion at center stage. . . .

What do the data say? Does personal piety correlate with radical views? The answer is no. Large majorities of those with radical views and moderate views (94% and 90% respectively) say that religion is an important part of their daily lives. And no significant difference exists between radicals and moderates in mosque attendance.

Gallup probed respondents further and actually asked those who condone and condemn extremist acts why they said what they did. The responses fly in the face of conventional wisdom. For example, in Indonesia, the largest Muslim country in the world, many of those who condemn terrorism cite humanitarian or religious justifications to support their response. For example, one woman says, “Killing one life is as sinful as killing the whole world,” paraphrasing verse 5:32 in the Quran.

On the other hand, not a single respondent in Indonesia who condones the attacks of 9/11 cites the Quran for justification. Instead, this group’s responses are markedly secular and worldly. For example, one Indonesian respondent says, “The U.S. government is too controlling towards other countries, seems like colonizing.”

The real difference between those who condone terrorist acts and all others is about politics, not piety.

How do we explain extremists’ religious rhetoric? As our data clearly demonstrate, religion is the dominant ideology in today’s Arab and Muslim world, just as secular Arab nationalism was in the days of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Palestinian Liberation Organization — from its inception, a staunchly secular group — used secular Palestinian nationalism in its rhetoric to justify acts of violence and to recruit. Just as Arab nationalism was used in the 1960s, today religion is used to justify extremism and terrorism.

Examining the link between religion and terrorism requires a larger and more complex context. Throughout history, close ties have existed among religion, politics, and societies. Leaders have used and hijacked religion to recruit members, to justify their actions, and to glorify fighting and dying in a sacred struggle. (Who Speaks for Islam: What a Billion Muslims Really Think, pp. 72-74)

.

Robert Pape, in Dying to Win produced masses of research data (I have posted some of it here in several posts, including “terrorism facts” #2 and #3), and a wealth of interview material with suicide terrorists and their families and friends, and writes in his concluding chapter:

Understanding that suicide terrorism is mainly a response to foreign occupation rather than the product of Islamic fundamentalism has important implications . . . . Since the root cause of suicide terrorism does not lie in an ideology, even among Muslims, spreading democracy across the Persian Gulf is not likely to be a panacea . . . .(Dying to Win, p. 237)

(Some readers have scoffed at the idea of Western “occupation” of Middle Eastern countries. Pape’s definition of “occupation” was explained in Terrorism Facts #3.)

.

Riaz Hassan has authored several books and many articles. The two books of his that I have read are Inside Muslim Minds and Life as a Weapon. The latter is the more in depth study into the causes of suicide attacks. It is impossible here to cover the full depth of Hassan’s research and conclusions, so I will select a few lines from his second chapter in which he disputes the view that such terrorists are psychopathic or sociopathic deviants and that their suicides have what in technical jargon is called an “altruistic” motive. That is, the motive is viewed as a sacrifice for the benefit of a community with which the terrorist strongly identifies.

In short, altruistic motives are significant in explaining the moral logic of suicide missions. By their very nature, suicide missions involve collective motives and are sponsored by organisations that go to great lengths to embed themselves in the surrounding communities and pursue socially acceptable political objectives. Through their political and social activities these organisations create altruistic conditions and opportunities for their members to volunteer to sacrifice for the community if they wish to do so. The individual may be driven to self-sacrifice by the social and psychological traumas arising from the conditions of the war zone and/or teh absence of recourse to solutions to perceived injustices. Under such conditions the feelings of rage and revenge act as the means to set the scales of justice right. The individuals who wish to sacrifice for their community can be confident that the act is understood as such. . . .

Studies of the role, function and nature of terrorist organisations and altruistic motives as the driving force behind suicide bombings provide holistic and rounded explanations. In general they show that suicide bombings are a weapon of the weaker non-state entity engaged in asymmetrical conflicts with well-armed state armies. The conflict invariably involves liberation of the homeland. . . . The ultimate goals are political and not religious, but religion can mobilise both support and participation because of its emphasis on redemption and martyrdom. Individuals may be driven to self-sacrifice by a cocktail of emotions including pride, honour, anger, rage, humiliation, shame, powerlessness and hopelessness. . . . (Life as a Weapon, pp. 48-49)

.

Scott Atran emphasizes the importance of group dynamics for understanding how personal identity and behaviour are determined. His views derive from (1) his own fieldwork and psychological studies with terrorists and would-be terrorists and their friends and families, and from (2) his reading of evolutionary biology and human history:

Where do these two lines of evidence come together? In the fact that jihad flights with the most primitive and elementary forms of human cooperation, tribal kinship and friendship, in the cause of the most advanced and sophisticated form of cultural cooperation ever created: the moral salvation of humanity. To understand the path to violent jihad is to understand how universal and elementary processes of human group formation have played out in history and have come to this point. . . .

In August 1996 . . . Bin Laden issued a fatwa declaring war on the United States.

The fatwa clearly articulated the new goals of this movement, which were to force America out of the Middle East so that the movement would then be free to overthrow the Saudi monarchy or the Egyptian regime and establish a Salafi state. . . .

But the jihadi movement today is no longer under the control of the Al Qaeda terrorist organization and is no longer primarily aimed at freeing Muslim homelands from perceived occupiers. It has become the speckled fight of small, self-organizing groups of mostly young men who dream of belonging to a revolutionary global Islamic movement that would dispense Islamic justice. . . .

As the social movement has spread to the diaspora, it has become increasingly global in scope and apocalyptic in vision. That’s the bad news. But as it washes through the margins of societies, it has also become more scattered and disjointed — materially, psychologically, and philosophically. And that’s probably the good news. . . .

Jihad is a team and blood sport for morally outraged and glory-seeking young men. . . .

Islam and religious ideology per se aren’t the principal causes of suicide bombing and terror in today’s world — at least no more than are soccer, friendship, or faith for a better future. What is the cause of the current global wave of terrorism, then? Nothing so abstract or broad as any of these things, but bits of all of them, embedded and acting together in the peculiar sorts of small- and large-scale social networks that are emerging in this time in history.

Throughout human history, it is commitment to a religious or transcendental dream that ultimately sustains cooperation and competition between large groups, including the motivation for people to kill and die for others who aren’t genetic kin. We’ve also seen that the connection of the jihadi nightmare with Islam across the world and the centuries is only fragmentary and diffuse. . . . (Talking to the Enemy, p. 35, 103, 328, 425-26. )

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

While three of the horsemen, Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens, have lost their heads regarding Islam, I certainly respect their right to be as strident as they want in their advocacy. I can’t stand the tone trolls and you’re not helping types.

I would like to see more info and discussion of the reason your way out of faith argument. Certainly Atran is right that religion can be impervious to reason, but it’s clear that some people have cast off religion from reading books. Is there more rigorous evidence on this question out there?

I’m currently reading “In Gods We Trust” which is Atran’s analysis of the nature of religion. That was the source of my “Fantasy and Religion” post. The only material I have read on deconversion is older material addressing responses to cult members. Putting that together along with my own personal reflections I don’t think I will be saying anything new by suggesting people ‘deconvert’ when the ‘time’ is right for them — that is, when experiences come together in a certain way to make them rethink things.

The most useless way of trying to deconvert anyone is by arguing with their religious or doctrinal beliefs. I think it’s real-life life-changing things that open many minds to new ways of thinking/re-evaluating their beliefs.

Many people are tied up in religions because of peer pressure, too — or for any sort of social reasons. I can imagine such people not being very committed believers in the first place and being more open to “rational argument” against their beliefs. I am also sure there are atheists who mix with their religious friends and families on a regular basis in all faiths — and never bring themselves to let on to anyone.

Deconversion from cults might require confronting members with undeniable and overwhelming evidence that their organization or leaders are not what they present themselves as being. But I don’t know of any comparable method when it comes to filtering people out of mainstream religions.

I’m sure there are other studies out there that have looked into this. I’d be interested to read them.

One thing is for sure. People don’t become religious believers because of the rational arguments that persuade them of propositional truths — despite what they say and believe at the time. Such arguments are usually rationalizations. The proof of that is that rational argument is useless against the circularity and unfalsifiability of their beliefs.

Well, what do you know. Following Harris can provide some light and not just heat. This right on topic. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=orW1AstN7AI

I would have liked Paul Boghossian to have dwelt on a few more successful case studies. I kept thinking back on my own believing days and the way we were regularly questioning how we knew what we believed. A few nonbelievers did indeed ask me what it would take for me to lose faith in my beliefs, to come to accept my beliefs were wrong — just as PB suggests near the end of this video, with the assurance that such a question creates a “cognitive space” in the believer. There was no “cognitive space” of the sort he describes that was created in my mind by such a question. In fact, in time, the very thing I had said would overthrow my faith did happen.

Did it overthrow my faith as I predicted it would? Of course not. It simply meant, in my own mind, that I had more to learn and understand about my faith. My experience here was exactly as Scott Atran describes the nature of religious belief in “In Gods We Trust”.

The Bible itself assures the faithful that their faith is a gift from God. If a sceptic asked me a question that pulled me up and made me think about a particular angle for the first time, it did not mean — as PB says it means in one of the examples he gives — that a doubt was being planted in my mind for the first time and that I was a tiny step closer to the next stage of questioning my belief system. Not at all. It only meant that there was another question I needed to think through, usually later with fellow-believers, as we grew in our own understanding of our faith. We would think of ourselves as having “deepened” our faith for the experience.

I am not saying it is wrong to try to raise questions with believers. Doing so may really lead people out of faith if they were already candidates for leaving on other grounds. But as for a “method” to undermine faith more generally I would need more evidence that this strategy worked before I am convinced.

For the record, I make a distinction between online and in person. The atheist movement as a whole needs some people to push the boundaries and be strident or even mocking. In person, a single person should approach a believer completely differently. While I never try to dis-evangelize in real life, if I did I wouldn’t be a dick.

I think most of us love Dawkins’ famous line

Witty mocking of religion is very often good for a laugh. I have no problem with that. I also agree with your point about the difference between trying to argue with one personally over their faith and publishing propositional arguments against religion as part of a public discussion. Atran’s point, I think, is that such arguments are not likely to get us very far unless they are made with consideration of a good understanding of the nature of religion itself. It is not necessarily “weak-mindedness” or infantile naivety that makes the religious mind. People who have studied or experienced religious cults know this well. It’s not surprising to find them excluding the weak-willed from their membership. Any of these who do join rarely last long. Strong idealism is critical factor.

The flip side of this interests me – Christian apologists. They surely came to faith emotionally like almost everybody else. But as opposed to almost everybody else, their driving force is to rationally justify their faith. Why? Prove to other people they are really smart? (More like good rationalizers) Bolster emotional faith by rational means, if that is possible? Do they think they can bring atheists or nones to Jesus?

I have a personal connection to these questions. My brother-in-law is a really smart guy, academic scholarship and good grades in Russian literature at Dartmouth. After graduation, he probably was on his way to a PhD when he found Jesus in remote Siberia – all of sudden he felt “God/Jesus is love”. A pure emotional moment. Now he is a good preacher in a conservative Lutheran church (part of a group that broke away from the ELCA). His dream is to be like Ravi Zacharias (who somehow floats below the atheist radar but is very popular). I can’t fathom why. I’ve never been a believer, so we are coming from different planets. We’ve had some religious discussions, but only see each other once or twice a year, so mostly we keep it real and play with our kids. I wonder if he even has the self-awareness or words to explain it to me.

Anyone have any insight on this?

In Gods We Trust cites dozens of studies that have linked “spirit possession, sudden conversion and mystical experience” with a range of negative psychological conditions.

And

One explanation is that stress disrupts existing patterns of thought and behaviour which then become dysfunctional. (e.g. prolonged bereavement). This brings the opportunity for new or suppressed patterns to assert themselves. A life crisis, dissatisfaction, a feeling of being ill at ease with oneself . . . .

I’d like to understand more about how such feelings trigger either a sudden conversion (or deconversion).