Continuing from the Jesus and Dionysus (2): Comparison of John’s Gospel and Euripides’ Play . . . .

It would be a mistake to confine our comparison of the Gospel of John’s Jesus with Euripides’ play. Bacchae has no reference to the Dionysian miracle of turning water into wine (see the first post in this series for details) yet numerous commentators on the Gospel’s Cana Wedding miracle of turning water into wine have pointed to resonances with the Greek counterpart.

Further, it would be shortsighted to dismiss any comparison of the Gospel’s Jesus with Dionysus on the grounds that there is no obvious link between Jesus’ crucifixion and the dismemberment (the sparagmos) of the enemy of Dionysus.

Suffering and Power

In fact, when the god’s enemy undergoes humiliation and dismemberment he is really sharing in or identifying with the sufferings of the god. His name is, after all, Pentheus, with verbal resonances with “pathos” (suffering); and we have seen that the purpose of the god is to come to relieve the suffering of humanity through his gift of wine, and the play itself speaks constantly of the suffering that Pentheus must undergo as punishment for his attempt to thwart the purpose of the god. It is through the suffering of Pentheus (identifying with the sufferings of the god) that the god who comes in apparent weakness, as an effeminate mortal, is exalted — his victorious and divine power is displayed for all!

The “discovery of Dionysiac echoes in John’s story as a whole” (Stibbe, p. 2) — in particular with the miracle of Cana, (the identification, one might add, of Jesus with the vine itself), the binding of Jesus, the dialogue with Pilate and the pathos of Jesus’ crucifixion — requires us to look beyond the tragedy itself and to look at all that the myth conveyed.

Indeed, there are other myths where Dionysus inflicted the same punishment upon others apart from Pentheus. King Lycurgus of Thrace also opposed the worship of Dionysus. Dionysus punished him by sending him into a mad frenzy during which he dismembered his own son; subsequently his citizens pulled him apart limb by limb in order to remove the curse of Dionysus from their land.

An early form of the myth is that Dionysus was originally born to Persephone, queen of the underworld (Hades). (It is not insignificant, for our purposes, that some of the myths tell us Zeus intended this new child to be his heir.) The jealous wife of Zeus (Hera) who had fathered the child persuaded the evil Titans to destroy the infant. Attempting to avoid capture by the pursuing Titans Dionysus changed himself into a bull, but was caught in this form and pulled limb from limb. The Titans then devoured these dismembered pieces of flesh. Zeus punished them by destroying them with thunderbolts, and from the ashes humankind was created, a mixture of the evil of Titans and the divinity of Dionysus.

Twice Born, from Below and Above

Through all of that chaos one piece of Dionysus was rescued, his heart, which was returned to Zeus. Zeus used the heart (the myths and means by which he did this vary) to give Dionysus a second birth, so he became known as the “twice-born” god.

A later version of the myth, the one that lies behind the play by Euripides, is that Zeus had fathered Dionysus with the mortal woman, Semele. Again Hera sought to kill the child, this time before it was born, by challenging Semele to see Zeus in all his glory. When Zeus showed himself in all his godliness Semele, of course, was struck dead. But Zeus rescued the child from her womb and sewed it into his thigh until it was ready to be born a second time, from the god himself.

Anyone familiar with the Gospel of John does not need to be reminded of Jesus explaining the mystery of being born a second time from above.

So we are beginning to see that the water into wine miracle in the Gospel of John, the one detail that strikes many commentators as redolent of Dionysian associations, is not the only such Dionysian echo in the Gospel.

Like Dionysus, Jesus was “twice-born”, once from below and once from above, both human and divine in nature; like Dionysus, Jesus was exalted when mortals entered into his own sufferings; like Dionysus, Jesus came to remove suffering from mankind; like Dionysus, the Jesus in John’s Gospel is symbolized by the wine and the true vine itself, and his body is vicariously broken and eaten; like Dionysus, Jesus teaches true wisdom that the princes of the world cannot see or understand and that they necessarily oppose; like Dionysus, Jesus comes as an unrecognized stranger into the world and his few followers are persecuted; and readers will probably notice others I have overlooked here.

What possible connection could there be, however, between such a crude pagan myth and the sublime theology of the New Testament?

Symbolic Mystery

In wondering about that it is useful to notice that Plato did not accept the literal meaning of the myths, and is thought to be alluding to the separation of limb from limb in the Dionysus myth when he wrote:

But the virtue which is made up of these goods, when they are severed from wisdom and exchanged with one another, is a shadow of virtue only, nor is there any freedom or health or truth in her; but in the true exchange there is a purging away of all these things, and temperance, and justice, and courage, and wisdom herself are a purgation of them.

And I conceive that the founders of the mysteries had a real meaning and were not mere triflers when they intimated in a figure long ago that he who passes unsanctified and uninitiated into the world below will live in a slough, but that he who arrives there after initiation and purification will dwell with the gods. For “many,” as they say in the mysteries, “are the thyrsus bearers, but few are the mystics,” — meaning, as I interpret the words, the true philosophers. (Phaedo)

Myths were being interpreted symbolically or allegorically to point to higher spiritual truths.

Will Draw All Humanity To Me

The Gospel of John uniquely speaks of Jesus drawing all mankind to himself. This is also one of the key messages attributed to Dionysus. He wore the Phrygian cap of Asia but his home was in Greece; he was born male but had to dress in female clothing to hide from Hera. He broke down the barriers between the races and the sexes in his own person. He was originally intended to be the heir of the old deity, Zeus.

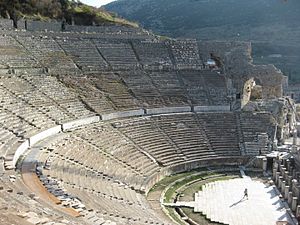

It is very difficult not to wonder in this context what was going through the evangelist’s mind when he, living probably in the Greek world of Asia Minor (Ephesus?), chose to portray Jesus the way he did . . . .

Continuing . . . . .

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Preposterous. You create literary comparisons and suggest historical connections where they do not exist. It is such a burden to go through material as you’ve included in the above post, dig out its groundless suggestions and demonstrate the lack of regard you have for your literary texts and cultural contexts.

I’ll not take time to go through details of your Jesus-Dionysus theory, but below is an analysis another such game you play that demonstrates how superficial your methods are when you go into one of these sophomoric diatribes.

____________________________________________________________________

“The Feeding of the 5,000 and the Feeding of the Sons of the Prophets:

A Comparison and Contrast Between 2 Kings 4:38-44 and Mark 6:30-44”

[To appreciate and evaluate this presentation, you need to have, open before you, the texts of both the story in 2 Kings 4 and the story in Mark 6, because direct references are made to the phrasing in each.]

Neil Godfrey claims to have evidence that the story of Jesus and the Feeding of the 5,000 in Mark 6:30-44 is derived from the story of Elijah and the Feeding of the Sons of the Prophets in 2 Kings 4:38-44. (http://vridar.info/xorigins/sources/mark/5000.htm)

Below is a numbered sequence of suggested parallels in the stories that Godfrey offers as evidence for his claim. Then in bulleted points, I respond to his suggestions.

1. Godfrey: Elisha went to a place where there was a famine in the land. / Jesus went with his disciples to a deserted place where there was no food.

• But Elisha, by himself, returned to a specific place, Gilgal. (Others were already there. It was a populated town and was not deserted as was the destination in Mark’s story.) / Jesus took his disciples with him to an unnamed place where lots of people did not usually go.

• There was a famine in Gilgal as Godfrey indicates – a fact that is strongly emphasized in 2 Kings. / But there was no famine where Jesus and the disciples went. Moreover, counter to Godfrey’s claim, no scarcity of food is indicated, to any degree, in Mark’s story. Instead: (1) Part of the reason Jesus took his disciples to the deserted place was to have time for quiet meals – time which they did not have in the midst of ministry. (2) The only reason the disciples gave for not feeding the multitude that arrived and interrupted their plan was the high cost of buying that much food from farmers and villagers that were nearby.

2. Godfrey: The followers (‘sons’) of the prophets were sitting before Elisha. / All who recognized Jesus went out to him, and in the course of the story he had them all sit down.

• But the sons of the prophets voluntarily adopted the sitting posture of students before a teacher. / In Mark 2: (1) The crowds sat down, because Jesus told his disciples to have them be seated. (2) Unlike the sons of the prophets, the multitude was seated in order in order to eat.

3. Godfrey: Elisha wishes to feed them. / Jesus commands that his servants feed them.

• But it is stated explicitly that Elijah told his servant (singular) to prepare a meal for the sons of the prophets (also called “men” and “people”) that eventually would need a miracle to get rid of its poisonous effect – a part of the story that Godfrey ignores in his analysis. Later the servant is instructed to expand the meal after a gift of bread and grain is brought to Elisha. / In Mark, the disciples who eventually helped serve a meal – without preparing it as Elijah’s servant did – are never called “servants” as Godfrey suggests. (The common use of “servant” in each story would seem to be a minimal evidential requirement for an actual linguistic parallel of the kind Godfrey suggests.)

• In 2 Kings, Elijah initiates the task of providing a meal. / In Mark’s story, the disciples – not Jesus – brought up the idea of the crowd going somewhere to get food to eat.

4. Godfrey: They have small quantities of 2 types of food: 20 barley loaves and newly ripened grain. / They have small quantities of 2 types of food: 5 loaves and 2 fish.

• But as already stated Godfrey ignores the most dramatic feature of the story in 2 Kings, the poisoning of the pot of stew and Elijah’s remedy that provided the larger part of a meal shared by the sons of the prophets – an event that occurs before the arrival of the barley loaves and newly ripened grain. / Nothing in Mark’s story parallels this outstanding feature of the story in 2 Kings, which is the most likely explanation for Godfrey’s omission of it and the most obvious indication that the two stories have no strong linguistic and literary connection.

• What is the parallel between “20” (in 2 Kings) and “5” (in Mark); and an unnamed quantity (in 2 Kings) and “2” (in Mark)? And what is the parallel between newly ripened grain (in 2 Kings) and fish (in Mark)? Furthermore, what is the parallel between: (1) a gift offered to Elisha (the man of God) in a time of local famine – from the firstfruits of a harvest outside of the locality – and (2) the five loaves and two fish that the disciples happen to have in their possession? / It is obvious that Godfrey’s parallels are forced. There is no wording in Mark that suggests he has copied 2 Kings on either the amounts or types of food that appear in his story. And there is no correspondence between the firstfruits of harvest in the earlier story and a small quantity of bread and fish in the latter story. Furthermore if Godfrey had kept in view the pot of stew, with its various ingredients, he would have to say that the sons of the prophets (the men, the people) were fed with – more than – two types of food.

5. Godfrey: His servants protest that they have too little food. / His disciples protest that they must send them away to find food for themselves.

• But Godfrey’s explanation, on this point, is inaccurate and is wholly out of sequence, regarding what we read in Mark 6. In 2 Kings, as Godfrey states, Elijah’s servant (singular, however, not plural as Godfrey puts it) protests his suggestion of feeding 100 with so little food. / However, in Mark, Jesus’ disciples first suggest having the multitude go get their own food and feed themselves. This suggestion is not a protest or response of any kind to something Jesus said or did. Later, they protest having to spend an enormous amount of money to feed so many – money they may not have had – after Jesus initially told them to feed everyone. But later, when they discover the 5 loaves and 2 fish, they do not protest that the amount is insufficient – when Jesus instructs them to have the multitude be seated in order to be fed. Godfrey’s sequencing is wrong. Apparently his desire to find literary parallels got ahead of a simple reading of obvious contrasts in the two stories.

6. Godfrey: Elisha overrides their objections and orders his servants to feed the crowd with the little they have. / Jesus overrides their objections and has his disciples feed the crowd with the little they have.

• Note that Godfrey continues to use plurals where singulars appear in 2 Kings 4. In this way, he seems to have convinced himself that Elisha’s non-existent servants parallel Jesus’ servants (his disciples, who are never called servants in Mark’s story).

• It is true, however, that Elisha’s servant (singular) does question the reasonableness of the prophet’s belief that his somewhat small gift from the man from Baal-shalishah was enough to be shared with everyone. And Elisha “overrides” him by proceeding. / However, as already indicated, there is no protest from Jesus’ disciples as he moves forward, using a few loaves and fish to feed the multitude.

7. Godfrey: Elisha said God had promised there would be more than enough. / Jesus prayed to God to bless the food.

• But a promise from God, with the advance statement that some food would be left after the meal is not a parallel to: “And He took the five loaves and the two fish, and looking up toward heaven, He blessed the food and broke the loaves and He kept giving them to the disciples to set before them.” / If Elisha had prayed, and his prayer was expressed in similar language; or if Jesus had stated a promise from God about how abundant this meal would be, then – and only under one condition or the other – could a serious parallel be suggested.

8. Godfrey: They all ate. / They all ate.

• Definitely, this is a parallel; but it is not sufficient to suggest a strong literary tie between the stories in light of all the data discussed above and below.

9. Godfrey: And there was some left over. / And there was much left over.

• 2 Kings does indicate, specifically, “there was some left over,” but the story indicates no cleanup afterwards and no quantities of how much excess food there was. / However, the story in Mark does – not – include the words, “there was much left over.” Instead, it is asserted, “they picked up twelve full baskets of the broken pieces, and also of the fish.” Godfrey’s contrasting statements of “some” and “much” – had the latter been included in Mark – would have provided a possible linguistic parallel.

10. Godfrey: 100 men were fed. / 5000 men were fed.

• But 100 has no obvious or symbolic correspondence to 5000. Likewise, there is no linguistic parallel in the sentences where the numbers appear. “What, will I set this before a hundred men?” (2 Kings) is wholly unlike “There were five thousand men who ate the loaves.” (Mark). So in actual wording, 2 Kings does not say 100 men ate, while Mark does say 5000 men did. / Again other possible expressions come to mind that would suggest parallels – if they were found in both stories – but none of these are in the actual texts.

Conclusion:

Godfrey works on the assumption that a story told about Jesus could not include actual memories of him if the story is modeled after some traditional story of a hero of Israel.

His assumption is invalid in the first place.

But aside from that general error, his treatment of the Feeding of the Five Thousand in Mark in comparison with the story of the Feeding of the Sons of the Prophets in 2 Kings is an unsound example of literary dependence that does not help his case.

Actually where I do refer to literary comparisons at all in the case of Dionysus and Jesus I am relying entirely on the work of the pastor and (I would even say conservative) theologian who does not at all believe the Gospel was directly copying the play, and who appears quite disposed to believe in a miracle-working real historical Jesus. This is the source of my literary parallels — as you should know if you read my posts.

But you are wrong to say I assume that a story about Jesus could not actually include memories of him if the story is modelled after some traditional story. I have never argued that. I don’t believe that. That is not my assumption. I know of many ancient and modern stories based on eyewitnesses and actual memories that are still modelled after traditional heroes.

So you are mistaken when you say that is how I am arguing.

So I invite you to try once again to tell me what my assumptions and basis of my arguments actually are. I have explained them often enough. If you really don’t know and give up then I’ll tell you.

When you wrote the original post to which I was responding (Elisha-Jesus), you were very clear about what you were — not just assuming — but actually stating concerning your lack of confidence in Mark as a resource of memories about Jesus. There you gave your readers a clear choice: either eye-witnesses were back of the story of the Feeding of the Five Thousand (via Richard Bauckham) or Mark “adapted his story from [a] literary source.”

So it is not accurate for you to say that you “have never argued that…a story about Jesus could not actually include memories of him if the story is modeled after some traditional story.”

I took the time to analyze your Elisha-Jesus parallels and sent you the results. They are very specific. So rather than run afield discussing what you assume and why you send out such posts as the Jesus-Dionysus parallels, you should respond to objections raised about what you did with the stories from 2 Kings and Mark.

You are quite correct to say that I have argued there is no evidence for some stories being based on eye-witness testimony but much evidence they are based on other literature.

But you are quite incorrect to say that I have ever argued or assumed or believed that a story about Jesus “COULD not actually include memories of him if the story is modeled after some traditional story.”

Of course many stories based on biographical facts are modeled after traditional stories. The point is that if we have evidence that a story is based upon another text and no evidence that it derives from historical memories then we have no grounds for believing that the story was historical or anything but literary. That’s simply a matter of accepting the evidence and lack of evidence.

So far the only “evidence” anyone has produced that at least one of the miraculous feeding stories of Mark was based on eye-witness memory is the story’s detail that the grass was green.

Now of course there may be evidence that is now lost and maybe one day we will uncover more things to change our minds. That’s why all our knowledge is always tentative. But tentativeness is not excuse to be perverse and argue a faith position contrary to the available evidence of available to us now.

On the other hand, there is evidence that the gospels’ stories were not based on oral tradition — which is what your model assumes. I am still to do posts on Henaut but have posted a few on Brodie and their analysis of the evidence for oral tradition in the gospels. I have also exposed at least one biblical scholar’s claims for support of a highly respected oral historian as less than professional “quote mining” contrary to the whole theme and thrust of that historian’s arguments. If you know of any arguments that support orality that are not based on mere assumption — or that are not contradicted by the evidence within the texts themselves — I’d like to know.

I have addressed the sorts of arguments you have made about the parallels many times in posts here. Suffice it to say that your same approach could prove that the Aeneid owed nothing to Homer’s epics and that all the ancient literary testimony to the methods, importance, practices and purposes of “mimesis” is entirely fraudulent.

Your criticisms are, moreover, entirely overlooking the facts of the way literary texts were copied — and the ways in which writers themselves said they copied and adapted them — in the literary culture from which the Gospels emerge.

But you seem to have misread the post here — I am not arguing here for intertextuality at all. Quite something else.

Besides, I do hope you don’t see my posts as an attack on the Bible or anything like that. I really love learning about the Bible and what we can discover when we step outside our assumptions and faith positions and investigate the tangible evidence for its origins.

You give a clear option in your post that compares a story in Mark and an earlier story in 2 Kings. And the option is:

EITHER historical event OR narrative based on a similar story. You don’t state or suggest a third possibility (The third option would be: BOTH historical event AND adaptation of a similar story).

The beginning of your post offers nothing but ten points that you claim are shared by both the story in 2 Kings and Mark. So you cannot now state that you had other evidences in mind — as you suggest in your last comment. (There can be no unstated evidence in a compact, simple-to-understand presentation such as you gave in the beginning of your post.)

You ask: “Is this story [in Mark] a unique historical event that was related by eyewitnesses or do we have evidence that the author was basing this narrative on a similar story or stories well known to him?”

If you had had in view, a third option (BOTH based on an actual event AND based on a similar story), then demonstrating that Mark had adapted a story in 2 Kings would not lead to the either-or options you originally posit.

So now, to be consistent, you would have to say, in fact, there is a third option; and your comparison of the stories does not demonstrate a lack of possible eyewitness testimony.

Then early on in your post on Jesus and Dionysus, you state, “…the Christ we read of in the Gospels is a myth. These posts are merely attempting to identify one source of one of those mythical portrayals.”

You stated, in a comment to me, that you are citing the work of a “conservative” pastor, who does not think the Jesus of the Gospels is a myth. Yet purely and simply, you are citing his work in order to demonstrate that the Gospel of John is mythical.

You assume, from the outset, that any similarities to myths in John’s Gospel — no matter how strained and removed from the actual texts the similarities may be — indicate nothing but myth in John. (As with the Mark-2 Kings analysis, you suggest no third option.)

But let’s stop talking about all this.

I asserted that your comparison of the story of the feeding of the sons of prophets with the story of the feeding of the five thousand in Mark is far-fetched and ludicrous. And I gave specific reasons for the assertion. (I see the same problem with a quick read of the Jesus-Dionysus comparison.)

Your last comment meanders and sets out about a dozen, separate broad assertions that have little or nothing to do with a close analysis of my original comment. (It would take about a dozen separate, wide-ranging responses to handle all your assertions.)

I’ve noticed that this is a consistent tactic of yours. Rather than settling in on a single item of discussion and working on the pros and cons, you try to overwhelm your critics with a barrage of claims and references. And then, quite often, you dismiss your critic by stating that you’ve dealt with all this before.

So how about a close study of the problems I suggested in my original post. (Neil, this the THIRD time I’ve asked for this.)

Are you just wanting to pick a fight or would you like to try to understand what I’m saying? If there is no evidence for a story being based on historical memory and if there is evidence it is a mutation of an earlier story, then we are only left with one valid option.

If I tell you what I mean and and what my argument is and what it is not then you might try to understand my words in that light instead of insinuating I am somehow lying. Or do you think because I’m an atheist that I have no moral compass so you are given the authority of the Bible to judge me as you do?

You write: “Yet purely and simply, you are citing his work in order to demonstrate that the Gospel of John is mythical.”

Nonsense. You are exhausting yourself by jumping to conclusions. Read my posts and I explain exactly what I am trying to do. I don’t have to demonstrate that the Jesus of the Gospels is a myth. Everyone knows that. Well, most critical scholars of whom I am aware acknowledge that. That’s why the quest for the historical Jesus is such a quandary.

My “meandering and broad assertions” were my deliberate response to your reply. I am not the least interested in going through your points one by one because that would be a waste of time. I am not going to persuade you any differently.

What I am trying to say to you in my “meandering and broad assertions” is WHY I am not interested in engaging with your points one by one. We are coming from the question with completely different understandings that have no ability to talk to each other on that question. Besides, if you say my position is “ludicrous” and “preposterous” at the outset, then it is clearly going to be a waste of time trying to discuss the topic reasonably with you. You don’t exactly indicate you have an open mind to the question.

Let me tell you again: my literary analysis is based upon the norms of literary analysis and literary practices of the Hellenistic/early Roman imperial era. It is based on the way scholars have taught me — through the evidence — how the ancients wrote and how they used other texts.

I could approach the Aeneid in the same critical way you have approached the Gospel narrative and I would be able to demonstrate to you how ludicrous and preposterous it is to suggest Virgil was imitating Homer’s epics. Now if you really believe that your approach is valid and that we have no grounds for believing that Virgil imitated Homer then that’s fine. I would presume you have an informed argument.

If I were to go through each of your points one by one I would only do so if I knew you were acquainted with the way ancients practised literary mimesis. Then we would have some common ground from which to discuss the question.

P.S. Are you looking for new sermon material? Lesson this week: “How I confronted an atheist blogger who illogically is trying to argue Jesus is a myth!”

If you ever pick up an interest in understanding how ancient authors imitated older literary works you might look at: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2012/10/19/old-testament-based-on-herodotus-acts-on-the-myth-we-read-in-virgil/

That post will explain to you why the sorts of criticisms you make against what many scholars acknowledge is a literary borrowing in the Gospels miss the point. By demanding everything to be the same — no differences — then we would not have adaptation at all, but only a transcribed copy.

But if you’d rather go back to your church and tell them how you confronted this atheist with all the arguments against something he wrote and he couldn’t answer any of them but ducked and weaved and ran away then you might feel more comfortable just ignoring that post.

^This bullet-point list just seems like trying a differences-outweigh-similarities appeal. The trouble with that approach is that it can be done with just about ANY comparison between Old & New Testament stories, even the ones that the New Testament explicitly admits it deliberately borrowed from. For example, Jesus himself appealing to Jonah in the whale as analogous to his death & resurrection. Differences galore between those two things. The ONLY apparent similarity they have is leaving and returning after three days. Yet Jesus still pointed out the parallel, and expected other to see the parallel as well when he called it a sign. Jesus also likened his own crucifixion to Moses putting the bronze serpent on a pole- even though the differences outweigh the similarities. Same with him likening his crucifixion to the slating of the Passover lamb, or Paul likening it to posthumously hanging stoned criminals, or the author of Matthew likening the virgin birth to the birth of Immanuel in Isaiah 7 & 8, or likening the flight to Egypt to the Exodus reference in Hosea, etc., etc., etc.

Mr. Godfrey:

It is a waste of time to try to communicate with you.

You are good at ad hominem evasion and poor at a balanced discussion.

My background — if I were an accomplished scholar or an ordinary reader — is irrelevant. And the broad context of your posts and assertions are just as irrelevant.

I’ve asked you to discuss a simple point-by-point issue. It is obvious that you will never do so. You gave ten points of correspondence between 2 Kings and Mark 6; and I pointed out that your analysis was faulty throughout. But you don’t want to talk about it. Fine.

As I have been forced to do before, this will be my last post on another topic.

You finally got my point! 😉

By the way, have you read the Aeneid and the Odyssey by any chance? Or was I talking past you then? (And do take a valium. It’s not really an important enough question to get upset over.)

Neil began with a ten-point list of correspondence between a story in 2 Kings and Mark 6. He claimed that his list demonstrated that the story of the feeding of the five thousand in Mark was fabricated and had no witness value to an actual event.

It was HIS list that I was responding to.

As for your examples, there’s a lot of difference between, on one hand, using references from the book of Jonah, Exodus, or another Old Testament book to draw an analogy — even a prophetic or typological analogy — and, on the other hand, to take the major features of a complete story and re-work it into another.

Neil claimed he had specific, point-by-point comparisons between stories that showed the one was based on the other. I claimed he did not, because some of his comparisons were forced and others were non-existent.

Anna Nimus — And trying to balance differences against similarities actually misses the point and nature of literary imitation. Your note about the symbolism of Jonah, the bronze serpent, etc is significant — it reminds us just how arcane were the methods by which the OT was scoured for new meanings.

Absolutely the best articles out here showing the similarities between Dionysus and Jesus, and their respective sources!! Anyone disputing otherwise is simply in denial. I found your site while searching for a source that mentioned Dionysus turning water into wine before Jesus was said to have done it.. but I’m yet to find one dated from around 30 AD or before.. Christians say Dionysus did it after Jesus but I can’t find the definitive proof to refute. Other than context clues to support my position, is their an actual source in existence?? Please tell me there is! Thank you for your contribution and work in this field, it is very much appreciated!

Have a look at Wendy Cotter’s Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity — available to the public at https://archive.org/details/miraclesingrecor0000cott/page/164/mode/2up

Manu,

Neil is correct about the parallels between Dionysus and Jesus. Dionysus was associated with wine miracles long before Jesus. There’s a lot more similarities between Dionysus and Jesus besides wine miracles. Scholars have pointed this out.

On Marvellous Things Heard 842A, pseudo-Aristotle(4th century BCE):

>”In Elis they say there is a building about eight stades from the city into which at the Dionysia they place three empty bronze cauldrons. When they have done this they call upon any of the visiting Greeks who wishes to examine the vessels, and seal up the doors of the house. When they are going to open it, they show the seals to citizens and strangers, and then open it. Those that go in find the cauldrons full of wine, but the ceiling and walls intact, so that there is no suspicion that they effect it by any artifice.

Library of history 3.66, Diodorus Siculus (1st century BCE):

>”The Teans advance as proof that the god [Dionysus] was born among them the fact that, even to this day, at fixed times in their city a fountain of wine, of unusually sweet fragrance, flows of its own accord from the earth.”

The Natural History 31.13, Pliny the Elder (first century CE):

>”According to Mucianus, there is a fountain at Andros, consecrated to Father Liber [Dionysus], from which wine flows during the seven days appointed for the yearly festival of that god, the taste of which becomes like that of water the moment it is taken out of sight of the temple.”

Reading Dionysus: Euripides’ Bacchae and the Cultural Contestations of Greeks, Jews, Romans, and Christians (Mohr Siebeck, 2015), Courtney Friesen:

>”A juxtaposition of Jesus and Dionysus is also invited in the New Testament Gospel of John, in which the former is credited with a distinctively Dionysiac miracle in the wedding at Cana: the transformation of water into wine (2:1-11). In the Hellenistic world, there were many myths of Dionysus’ miraculous production of wine, and thus, for a polytheistic Greek audience, a Dionysiac resonance in Jesus’ wine miracle would have been unmistakable. To be sure, scholars are divided as to whether John’s account is inspired by a polytheistic legend; some emphasize rather it’s affinity with the Jewish biblical tradition. In view of the pervasiveness of Hellenism, however, such a distinction is likely not sustainable. Moreover, John’s Gospel employs further Dionysiac imagery when Jesus later declares, “I am the true vine”. John’s Jesus, thus, presents himself not merely as a “New Dionysus,” but one who supplants and replaces him… Like Judaism, Christianity was at times variously conflated with the religion of Dionysus. Indeed, the numerous similarities between Christianity and Dionysiac myth and ritual make thematic comparison particularly fitting: both Jesus and Dionysus are the offspring of a divine father and human mother (which was subsequently suspected as a cover-up for illegitimacy); both are from the east and transfer their cult into Greece as part of its universal expansion; both bestow wine to their devotees and have wine as a sacred element in their ritual observances; both had private cults; both were known for close association with women devotees; and both were subjected to violent deaths and subsequently came back to life…”

Dining with John: Communal Meals and Identity Formation in the Fourth Gospel and Its Historical and Cultural Context (Brill, 2011), Esther Kobel:

>”The Fourth Gospel alludes to the traditions of Dionysus in a number of other ways, as will be discussed in what follows… The earliest certain evidence of Dionysus’ association with wine is in the oldest surviving Greek poetry, dating from the eighth and seventh centuries bce. The most abundant evidence of Dionysus as the god of wine is found in Athenian vase-painting. Dionysus is associated with the production and consumption of wine and, as early as the fifth century bce, he is even identified with wine… This source—along with others—also indicates that Dionysus is envisioned as inhabiting the wine… The idea that this god inhabits the wine and gets poured out in libations is obviously widespread…Grapes and wine are the means of Dionysus’ epiphany to mortals. The idea of vine, wine and grapes representing Dionysus is clearly not simply a metaphor, but rather a way in which humans experienced this god. Dionysus is believed to theomorphize into the substances that he invented. Wine is frequently associated with blood. The notion of calling the juice of grapes blood is well known in many traditions, Jewish and pagan alike (for example: Gen 49:11; Dtn 32:14; Rev 17:6; Achilles Tatius 2.2.4). Unsurprisingly, wine also appears as the blood of Dionysus (Timotheos Fragment 4). The idea of Dionysus being torn apart and pressed into wine appears in songs that are sung when grapes are pressed…

>”The Johannine notion of a god appearing on earth and interacting with humans is not new at all, as has been demonstrated from the Dionysian traditions. Even the idea of a divine figure that dies and comes back to life is not peculiar to the Gospels. Jesus and Dionysus share the intermingled correlation of “murder victim” and “immortal mortal.” Just as Dionysus is an immortal mortal who has experienced human death and whose life is restored by the power of the gods, Jesus is killed and resurrected through the power of God. Through this resurrection, the “ultimate immortality confirms his divine status.” Furthermore, both Jesus and Dionysus have a divine father and a human mother… Dionysus and Jesus share other commonalities which support the suggestion that Dionysian traditions may have been on the radar of the Gospel’s earliest audience. Among all other deities in the Greek pantheon, Dionysus was the god who is said to manifest himself most often among humans. He was the one who appeared on earth in human disguise, but even in his human disguise he remained a god in the full sense. Dionysus and Jesus share the complicated and intermingled relationship of being divine or of divine descent, and of appearing human among humans. Both of them die and come back to life: they share the notions of being “murder victims” and “immortal mortals.” Eschatological hopes are vivid among the followers of Jesus, just as they are among followers of Dionysus. Followers of Dionysus turn to him and get initiated into his cults in hope of a better lot after death. The followers of Dionysus were originally rejected by their surroundings. Over the centuries, however, and certainly by the time of the Gospel’s origins, the cults had established themselves on a large scale, and Dionysian followers no longer feared persecution on the part of the Roman authorities.”

Instructions for the Netherworld: The Orphic Gold Tablets (Brill, 2008), Alberto Bernabé Pajares, Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal:

>”In the Gurob Papyrus there is an explicit mention of the fact that the initiate drinks to ease his thirst during the ritual, and wine is even mentioned, also in a context of liberation in which Dionysus appears as a savior god… In support of the interpretation of seeing in our text an echo of initiatory practices, we may mention several texts and figurative representations that inform us on the use of wine in this type of rite. Here, wine drinking was no simple pastime or pleasure, but a solemn sacrament, in the course which the wine was converted into a liquor of immortality… In a sense, drinking wine entails drinking the god: thus, Cicero (Nat. deor., 3, 41) does not consider it an exaggeration that some should believe they were drinking the god when they brought the cup to their lips, given that the wine was called Liber. Among figurative representations, we may cite an Italic vase in which Dionysus is carrying out a miracle: without human intervention, the wine pours from the grapes to the cups… Wine, a drink related par excellence to the mysteries of Dionysus, must have formed an essential part of the initiatory ceremonies that the deceased carried out during his life…”

Dionysos (Routledge, 2006), Richard Seaford:

>”Dionysos, like Jesus, was the son of the divine ruler of the world and a mortal mother, appeared in human form among mortals, was killed and restored to life… a secret of the mystery-cult was that dismemberment is in fact to be followed by restoration to life, and this transition was projected onto the immortal Dionysos, who is accordingly in the myth himself dismembered and then restored to life… this power of Dionysos over death, his positive role in the ritual, makes him into a saviour of his initiates in the next world… Dionysos could be called ‘Initiate’ and even shares the name Bakchos with his initates, but his successful transition to immortality – his restoration to life and his circulation between the next world and this one- allows him also to be their divine saviour. Plutarch (Moralia 364) compares Dionysos to the Egyptian Osiris, stating that ‘the story about the Titans and the Night-festivals agree with what is related of Osiris- dismemberments and returns to life and rebirths’…The restoration of Dionysos to life was (like the return of Kore [Persephone] from Hades at Eleusis) presumably connected with the immortality obtained by the initiates…”

Here’s one more source that goes into more parallels between the wine miracle in John and Dionysus. Not only was Dionysus known for wine miracles, but he was also known for “sacred” weddings (and triumphal entries but that’s another topic) and was referred to as being the bridegroom of his followers/initiates. Jesus’s wine miracle is performed at a wedding and he is referred to as the bridegroom.

‘Jesus und Dionysos. Göttliche Konkurrenz bei der Hochzeit zu Kana (John 2,1–11)’, Wilfried Eisele in Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft Volume 100 Issue 1 (2009):

>”When in the libation, which is common throughout antiquity, people donate wine before the gods, the god Dionysus himself is offered as a sacrifice to the other gods, then this means nothing other than that Dionysus is identified with the wine of the libation. These ideas are so widespread in antiquity that they can and must be assumed to be known and accepted by any Dionysus worshiper… With the evangelist the story in all probability acquires an even deeper meaning, namely a Eucharistic meaning. Just as Dionysus not only gives the wine but is the wine himself, so in the case of the miracle of Cana the gift of wine is identical with its giver Jesus. This eucharistic dimension does not follow directly from the story of Cana itself; but it gains plausibility if you look at it analogously to the bread multiplication and bread speech of Jesus in John 6:18 where the gift of the bread is expressly identified with the giver Jesus… The competition for the unsurpassable gift of wine is by no means the only motive that connects the story of Cana with the demonstrable worship of Dionysus… Panel 7 of the Dionysus Mosaic in Sepphoris depicts the marriage of Dionysus to Ariadne. The god is seated as the second figure from the left, leaning on his left elbow, and holds a shepherd’s staff loosely in his left hand… He directs his gaze to the right at his bride Ariadne, who in turn looks at him while holding a basket on her lap with both hands. Reinhold Merkelbach summarizes the associated myth as follows: ‘When Theseus had left Ariadne, who had been kidnapped by him from Crete, on Naxos, the unfortunate woman fell into a deep sleep. But the greatest happiness approached her. […] Dionysus appeared with the nymphs; these danced around the sleeping beauty. Then Dionysus raised Ariadne as his bride, and the marriage was celebrated at once. […] This wedding, with its rapture of the bridal couple into the heaven of happiness, was the mythical model for all weddings of the Dionysus mystics’. Again and again Jesus himself has been seen as the true bridegroom at the wedding in Cana… Anyone who makes the transformation of water into wine the only relevant motif in the whole story of Cana and only hears Dionysian echoes in it ignores a whole series of other important narrative features through which the story of the wedding at Cana is closely linked to the local Dionysus worship… On the other hand, if one takes the whole scenery seriously in its background meaning, starting with the wedding as the background story, through the wine, the mother of Jesus and his disciples to the question of the origin of Jesus, which is connected with all of this and already through John 1:19-51 is prepared, then one recognizes who is the unnamed and yet present in every narrative competitor of Jesus at the wedding in Cana – namely Dionysus.”

nightshadetwine,

Thank You much sir! Between you and Mr Neil, I definitely have the ammo to intelligently discuss in detail this topic when the situation necessitates. To me, it was always common sense that as popular as these myths were that they undoubtedly influenced the many myths that followed, especially that of Jesus. The evidence that you provided are like nails in the coffin. Which is how I like to finish a topic of this caliber. Curious, when researching the Solar Mythology of Jesus and how his story is an allegory of the sun’s path across the sky.. everything matches up so perfectly.. a question that some one might have is that « if the names of the characters and places like Pontius and Galilee and Bethlehem are allegories, how do they fit so perfectly and still be real places and people » I did find where location of Bible places were fabricated but I’m just wondering what your opinions are.. thank you!

https://www.solarmythology.com/

http://www.jesusneverexisted.com/galilee.html