Continuing from Part 1 of this series. . . .

The traditional use of the Bible

The central point of the previous post was that the Bible came to be viewed as having a singular message that buttressed a comprehensive an entire world view. That is, one’s larger view of the world was believed to rest on biblical authority.

Nineham gives “an example of how such a feeling arose”:

If the Bible spoke of angels, and these were interpreted in what then seemed the only way possible, as a group of hypostases, or entities, then it could easily seem as if the existence of the chain itself was a part of the biblical revelation, or at any rate an indisputable deduction from it. (p. 62)

The challenges of the natural sciences

As we all know, Copernicus and Galileo were the first to challenge seriously the Biblical view of the place of earth amidst the heavens. In the nineteenth century geology and evolutionary biology struck blows at the Bible’s creation narrative. The church’s reactions we also know well:

[I]t is instructive to notice the extent to which, both in the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, the immediate and passionate reaction of the Church was to try to defend the statements of the Bible in every sphere. (p. 63)

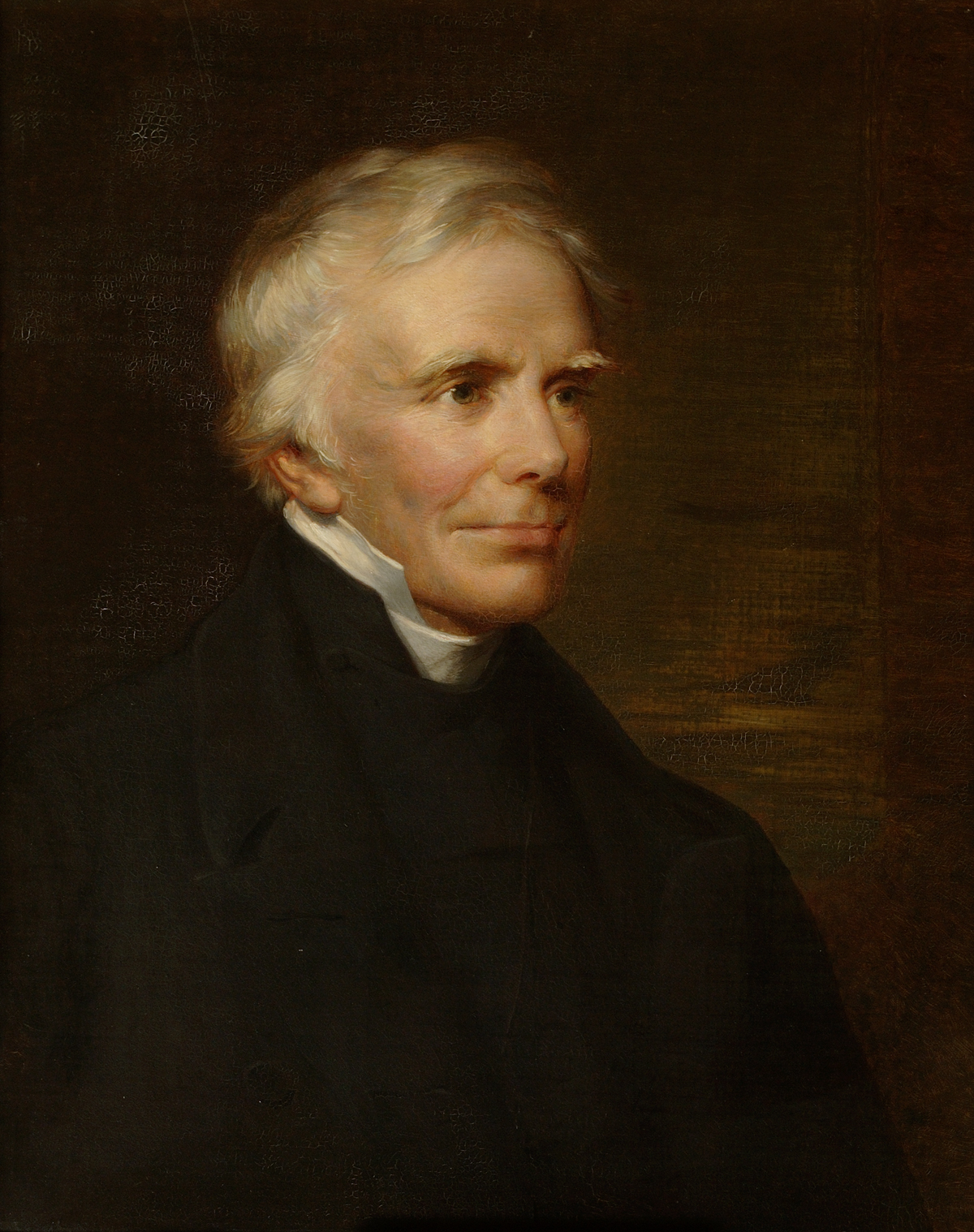

John Keble of the nineteenth century has left a useful trivia quote:

When God made the stones he made the fossils in them. (Presumably in order to test the faith of nineteenth century scientists!)

But the Bishop Wilberforces and Philip Henry Grosses could not win. It became increasingly clear, however slowly in some quarters, that flat denial of what the natural sciences had to come to understand was not going to prevail.

The early chapters of Genesis were at stake. The Bible was supposed to be authored by God and incapable of untruths.