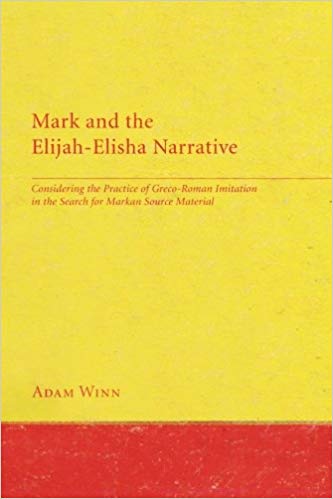

A lengthy interview with Emeritus Professor Robert Eisenman has been posted on the JesusMysteries Discussion Forum. Anyone not familiar with the name can bring themselves up to speed on Robert Eisenman’s Wikipedia page.

Dennis Walker writes by way of introduction:

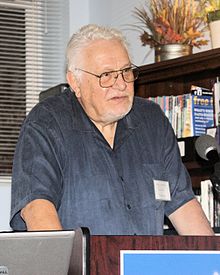

Clarice and I decided to ask Dead Sea Scroll scholar Robert Eisenman a few questions for the forum, and he generously responded. This is a long post, but I hope some who are familiar with his work over the years find it interesting. Eisenman isn’t quite a “mythicist,” but his work definitely put me on the road to questioning the existence of a historical Jesus, though ‘Jesus’ really hasn’t been his focus at all. Eisenman is now Emeritus Professor of Middle East Religions and Archaeology and Islamic Law at California State University, Long Beach.

I particularly liked Eisenman’s closing remarks:

Thank you for the opportunity of contributing to and participating in your web discussions. Keep up the good work, as they say, and don’t allow yourselves to be defeated or discouraged by any hostile ‘academicians’ or reputed ‘scholars’. These, in the end will always be the hardest either to influence or bring over to the kind of thinking you represent since they have the most to lose by either acknowledging or entertaining it, largely because they would be seen as somewhat ridiculous by their peers if they were to deny the whole thrust of their previous academic work and training.

We must leave them like this, but should not expect any different from them or be discouraged in any way by them. You are the final judge of these things and you have sufficient information and data at your fingertips to make your own final, intelligent, and incisive judgments which will hopefully be full of insight.

(My own highlighting in both quotations.)

It appears that Professor Eisenman will be available in the coming weeks to respond to any feedback and questions any of us may like to raise with him.

This looks like a very rare opportunity not to be let go. (And you don’t have to pay to enter a private forum, either.)

Physicist

Physicist