Continuing the series archived at Couchoud: The Creation of Christ – – – (Couchoud argues that our “editor” – Clement? – compiled 28 books, one more than our current 27 that make up our New Testament and this post concludes the section where Couchoud discusses the origin of our New Testament books.)

The perfect balance of the New Testament still stood in need of a counterweight. Just as the tale of Peter counter-balanced that of Paul in Acts, so the letters of Paul required as counterpoise letters from the Twelve. There were already in existence a letter by James and three by John. To make up seven, our editor produced two letters by Peter and one by Jude, John’s brother. (p. 305)

I don’t know if Couchoud here means to suggest “the editor” wrote these epistles himself. I find it difficult to accept the two letters attributed to Peter are by the same hand given what I have come to understand of their strikingly different styles, but let’s leave that question aside for now and cover what Couchoud’s views were as published in English 1939.

1 Peter

This epistle is said to have been a warrant for the Gospel of Mark. (Maybe, but some have suggested the name of Mark for the gospel was taken from this epistle. If it were a warrant for Mark one might be led to call to mind the unusual character of that Gospel. Its reputation had been tinged with “heretical” associations.) In the epistle Peter calls Mark “my son” and is supposed to be in his company in Rome, biblically called “Babylon”. The inference this leads to is that Mark wrote of the life and death of Jesus as learned from the eyewitness Peter. This coheres with Justin’s own naming of the Gospel “Recollections of Peter” in his Dialogue, section 106.

The letter is “a homily addressed to baptized heathen of Asia Minor at the time of a persecution.” Its teachings can be seen to be of the same category as those addressed in the earlier discussions by Couchoud – typical of Clement and anti-Marcionite . . .

- the Jewish prophecies were meant solely for Christians

- imperial authorities needed to be greatly respected — (Couchoud says that the epistle refers to Pilate as one who judges righteously in 1 Peter 2:23, but I always took that phrase as a reference to God.)

- the answer is given to the question of the fate of those pagans who had died before having a chance to be saved by the Blood of the Lamb: Marcion had taught that all the sinners of old were saved by Jesus when he went down to hell; this epistle was not to be outdone by Marcion’s teaching.

- Women should not plait their hair: 1 Peter 3:3. This links with the Pastoral prohibition of the same: 1 Timothy 2:9. “This plaiting of the hair was the fashion in the time of the Antonine dynasty — that is second century.

- Charity covers a multitude of sins, found in 1 Peter 4:8, is also found in 1 Clement 49:5

Jude

The brief Epistle of Jude is an affirmation that the Christian faith has been given “once for all” by the Apostles, and a violent condemnation of all who “in their dreamings defile the flesh and set at nought dominion and rail at dignities,” and those who would classify people into psychics and spirituals and have not themselves the Spirit. We can recognize in these the Alexandrian Gnostics, Basilides, Carpocrates, who sought the way of salvation in the freedom of the flesh, and Valentinus in particular. The latter came to Rome shortly before Marcion and attempted to force himself into the Roman episcopacy. His astonishing Gospel of Truth and his sacrilegious and disorderly theology stunned the faithful. (pp. 306-307)

2 Peter

This is said to be the most coherent of the three letters. It presents itself as a witness of Peter. Its middle section is mostly a repetition of Jude. And it has three particular aims:

- It addresses those disillusioned Christians whose hopes for the Coming of the Lord failed to materialize after their great expectations around the year 135, the second destruction of Jerusalem. (In support of this time-frame see my earlier post Identifying the “Man of Sin” in 2 Thessalonians.) Peter assures his readers that a day of the Lord is as a thousand years and a thousand years as a day. “So we have the impatient Christians put off to the year One Thousand.” We find Clement answering the same question with the same idea in 1 Clement 49:5.

- This epistle has Peter approve the “right edition” of Paul’s epistles — the ones doctored by Clement and co — and disapprove of the Marcionite interpretation. 3:15-16 warns that there are those who fail to understand Paul’s letters, and that “the ignorant and the unsteadfast falsify them, as also the other scriptures, to their destruction.”

- Peter also draws special attention to a book he is about to write so that after he is dead the faithful can recall certain things to their memories, for he had been with Jesus himself on the “holy mount” and heard a voice from the “excellent glory” speaking of His Beloved Son. “Evidently he had in mind a Revelation “more sure” than any other, including the Revelation of St. John: Go to 1 Peter 1:15-19. In this passage note μεγαλοπρεποῦς (and forms of this word = “majesty”) applied to God — “it is a favourite with Clement, appearing seven times in the Epistle to the Corinthians.”

And the work or scripture that “Peter” had in mind in point #3?

Probably . . . the Apocalypse of Peter. This work was intended by our editor to be the completion and perfection of the New Testament, doubling the older Revelation of St. John which was too hard for the Gentile and not over-edifying. Peter’s Revelation was used in the Roman Church till the end of the second century, but then lost ground before its powerful rival. (p. 308)

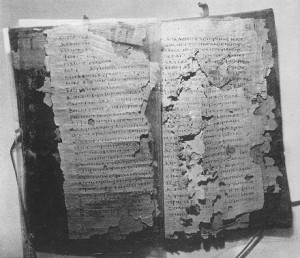

The Apocalypse of Peter

This Apocalypse or Revelation was listed as part of the canon by the Muratorian fragment and Clement of Alexandria quoted it as part of the New Testament according to Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History, vi. 14. 1.

Couchoud suggests that Acts 1:3 (speaking of many proofs Christ gave the apostles after his resurrection and speaking of the Kingdom of God) was inserted as a lead up to Peter’s Revelation.

This Revelation is presented as one of the “many proofs” Christ gave to his disciples during the first 40 days after his resurrection:

Jesus is with his apostles on the Mount of Olives, the “holy mount”.

They ask him of the Great Judgment which is to be preceded by the destruction of the fig tree.

Peter wants to know what fig-tree and the answer is the fig-tree in the parable in Luke — that is, the Jews and the false Jew Messiah who persecuted Christians (Bar-Kochba).

Then there would be false prophets teaching destructive doctrines (e.g. Marcion)

They pray with him (note that prayer is a characteristic of Luke) then ask to be shown the face of one of the elect.

Two glorious men appear before them (snow white, rose pink, rainbow hair, etc)

Peter sees a beautiful flower carpeted land with high priests living like angels on one side, and a fowl, slimy, putrid place where 14 kinds of criminals are being tortured. Aborted babies shoot forth flames of fire into the eyes of their blood-soaked tormented mothers.

The Elect are privileged to see these tortures and to obtain some remission for their loved ones in that place.

Jesus prophecies that Peter will die in “a great city of the West”.

Jesus then takes his disciples up to the top of the holy mount and re-enacts the Transfiguration

Jesus is enveloped in a cloud, thus giving a third account of the Ascension (cf. Luke 24:51 and Acts 1:6-12) and the apostles go down the mountain praising God who has written the names of the Elect in a Book of Life.

Couchoud’s assessment of this work:

What is lacking in this literary vision, which is in spirit more pagan than Biblical, is sincerity, power, emotion, spontaneity, glamour, and the mighty sweep of the lofty vision of the seer of Patmos. The age of the prophets had surely heard its last hour strike. (p. 309)

Thus completed the New Testament

This collection thus counted 28 books, four groups of seven. Later the Revelation of Peter was suppressed.

The first 14 Scriptures came from the Twelve Apostles and their authorized interpreters.

The first group of 7

- 4 Gospels

- Acts

- 2 Revelations

Their authors

- Matthew, John, Peter (apostles)

- Mark, Peter’s “son”

- The dedicator to Theophilus who had carefully collected the traditions of the apostles

The second group of 7

- 7 “Catholic” epistles — i.e. those addressed generally.

Their authors

- James, Peter. Jude, John (apostles)

The second set of 14 Scriptures are from the second group of apostles — Paul and Barnabas (assigning the Epistle to the Hebrews to Barnabas)

Between these two groups there is no conflict; on the contrary, harmony reigns. Peter approved Paul’s Epistles, and so the Twelve walk hand in hand with Paul and Barnabas. The link between them is that writer to Theophilus who was such a diligent historian of the whole brigade of Apostles. There were no other Apostles than those fourteen, and they wrote nothing beyond the twenty-eight Scriptures. Hermas’s prophecy cannot be accepted, as it is not by an Apostle. [The Muratorian fragment makes this explicit.] Such was the compact and numerous Bible, closely linked with the Bible of the Jews, which the great Church henceforward opposed to the Scriptures of Marcion.

This ingenious, bold, liberal, and prudent builder has a right to applause, for he constructed out of a hotch-potch of writings a coherent and durable whole, strong to resist and powerful to prevail. In it all spiritual needs are satisfied. Its preservation is entrusted to the colleges for whose authority it is itself the foundation. Not a source of riches has been neglected in its compilation. Books sown and ripened in differing climates find in it a common strength in which all are strong in the support of their fellows. The four Gospels in this association appear as four independent testimonies which mutually corroborate and complete one another. The critical historian may reproach the architect with building wings under false names, with repairs, renovations, and false windows. Still he will admit that the architect was driven by necessity, and that without him the most ancient Christian documents might have been lost or dispersed. (p. 310)

I began this latest series of Couchoud posts from half way through The Creation of Christ. After the first few chapters that I made available as pdf downloads I skipped the chapters where Couchoud discusses his views on how the Christian faith emerged and picked up his arguments for the creation of the New Testament. Before posting Couchoud’s final chapter I’ll backtrack and outline the gist of those earlier chapters.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!