Slightly revised 9th Feb. 2010, 3:00 pm

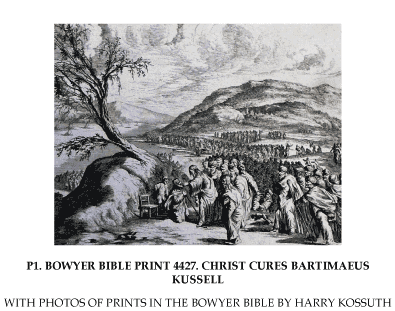

John Spong finishes off his chapter (in Jesus for the Non-Religious) about healings by discussing the healing of blind Bartimaeus as found in the Gospel of Mark and healing of the man born blind in the Gospel of John. I’ll be sharing material from an old article by Vernon K. Robbins about Mark’s treatment of the Bartimaeus episode. Spong covers much the same theme but in less depth. (The article I use is The Healing of Blind Bartimaeus (10:46-52) in the Marcan Theology, published in the Journal of Biblical Literature, June 1973, Vol. 92, Issue 2, pp. 224-243.) Will also draw on Michael Turton’s Historical Commentary on the Gospel of Mark.

John Spong finishes off his chapter (in Jesus for the Non-Religious) about healings by discussing the healing of blind Bartimaeus as found in the Gospel of Mark and healing of the man born blind in the Gospel of John. I’ll be sharing material from an old article by Vernon K. Robbins about Mark’s treatment of the Bartimaeus episode. Spong covers much the same theme but in less depth. (The article I use is The Healing of Blind Bartimaeus (10:46-52) in the Marcan Theology, published in the Journal of Biblical Literature, June 1973, Vol. 92, Issue 2, pp. 224-243.) Will also draw on Michael Turton’s Historical Commentary on the Gospel of Mark.

The story of Bartimaeus is constructed to inform readers that Jesus is greater than the traditional idea of the Son of David. The details of the story serve only to point out the identity of Jesus Christ and the meaning of discipleship. The healing of blindness is only the symbolic way in which these messages are conveyed. Take away the theological meanings of the story and it becomes a meaningless tale. There are no details left over that give us any reason to suppose that the story was ever anything more than a symbolic or parabolic fiction.

This is the story (Mark 10:46-52)

46 Now they came to Jericho. As He went out of Jericho with His disciples and a great multitude, blind Bartimaeus, the son of Timaeus, sat by the road begging. 47 And when he heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, he began to cry out and say, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!”

48 Then many warned him to be quiet; but he cried out all the more, “Son of David, have mercy on me!”

49 So Jesus stood still and commanded him to be called.

Then they called the blind man, saying to him, “Be of good cheer. Rise, He is calling you.”

50 And throwing aside his garment, he rose and came to Jesus.

51 So Jesus answered and said to him, “What do you want Me to do for you?”

The blind man said to Him, “Rabboni, that I may receive my sight.”

52 Then Jesus said to him, “Go your way; your faith has made you well.” And immediately he received his sight and followed Jesus on the road.

Bartimaeus, a contrived name

The name itself is surely contrived. While Richard Bauckham (who has courageously argued that the names mentioned in the gospels are the sources of eyewitness accounts of the events we read in the gospels) does not doubt the authenticity of the name, he does inform us that

Timaeus is a Greek name occurring only in this case as a Palestinian Jewish name. (p. 79, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses)

While it is not unusual in our surviving records to find a Greek name occurring only once as the name of a Palestinian Jew, there are a number of other details that, when brought together, argue against the probability that this was a real name. The most significant of these is that Mark refers to him as “Bartimaeus son of Timaeus”. Yet Bartimaeus itself means “son of Timaeus”, with Bar itself meaning “son”. This is not the only artificial name concocted by Mark. We later read of Barrabas, meaning “son of the father”. Spong remarks upon this striking presentation of the name (Bartimaues bar Timaeus) and makes the point that the author is clearly signalling to readers to pay attention and hear what message is about to be delivered through this particular person. Bauckham does not see it this way, and simply exclaims that what is written in the Gospel is not what the author meant to convey:

He could never have been called “Bartimaeus son of Timaeus” (=Bar Timaeus bar Timaeus!) (p. 79)

Someone has claimed that I misrepresent Bauckham here. I took it for granted that what I do say here indicates that Bauckham argues that the name of the blind beggar really was Bartimaeus, and hence the “son of Timaeus” is a translation of that name — but I did not dwell on all of this here in this post in any depth because I have already posted dozens of posts on Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses, including several in which he addresses the name Bartimaeus. A simple word search will bring these up on my blog. — note added 10th Feb 2010, 9:30 pm.

Let’s agree with Bauckham on this point and accept, contrary to Bauckham, that the name itself is an artifice.

Spong calls in the testimony of Matthew and Luke to support our conclusion contra Bauckham.

This is a strange designation, since Bartimaeus literally means son (bar = “son”) of Timaeus, so one wonders what secret message is being sent to the first readers via these words. The story is repeated in Matthew (20:29-34) and in Luke (18:35-43), except that in Matthew no name is given, and thus the confusion avoided . . . . When Luke repeats this story, he also omits the name . . . . (p. 83)

There would, of course, have been no confusion had Matthew and Luke simply dropped the repetitious “son of Timaeus” and left the Bartimaeus as a standalone name. Bauckham says this itself is a rare enough name to be entirely sufficient for identifying the person:

[I]t is precisely the rarity of the name that makes the patronymic entirely sufficient for naming Timaeus’s son. (p. 79)

On the other hand, it seems that Matthew and Luke thought there was something “wrong enough” about the name for them to avoid repeating it when they wrote their versions of this Jericho healing (Matthew 20:29-34; Luke 18:35-43).

Michael Turton on his Historical Commentary on the Gospel of Mark cites Rhoads’ Mark As Story:

“Bartimaeus” the name itself means “son of Timaeus.” It is typical of the author of Mark to use this type of dual construction. “The two-step progression is one of the most pervasive patterns of repetition in Mark’s Gospel. It occurs in phrases, clauses, pairs of sentences, and the structure of episodes” (Rhoads et al 1999, p49). This redactive pattern suggests that the name itself is probably invention.

The meaning of Timaeus

If the name Bartimaeus is contrived for the narrative then what might it mean, and what might be its significance for the story?

Robert M. Price sees the name’s significance lying in the description of Bartimaeus as a beggar. He is sitting on the roadside begging when he hears that Jesus is approaching.

The Aramaic form of the name is Bar-teymah, “son of poverty,” which means he is a “narrative man” — his name is a fictional device. (p. 96, The Pre-Nicene New Testament)

Continuing with a citation from Turton’s Commentary:

The name Timaeus is most familiar to students of the ancient Greek philosophy as the title of one of the more influential dialogues of Plato. Again from Michael Turton’s Commentary:

Timaeus is the name of a well-known dialog of Plato. In this dialog, Socrates — who will be executed — sits down with three of his friends, Critias, Timaeus, and Hermocrates. The dialog involves a discussion of why and how the universe was created:

“When the father creator saw the creature which he had made moving and living, the created image of the eternal gods, he rejoiced…“(Jowett translation)

Plato’s Timaeus also contains a long discussion about the eye and vision:

“And of the organs they first contrived the eyes to give light, and the principle according to which they were inserted was as follows: So much of fire as would not burn, but gave a gentle light, they formed into a substance akin to the light of every-day life; and the pure fire which is within us and related thereto they made to flow through the eyes in a stream smooth and dense, compressing the whole eye, and especially the centre part, so that it kept out everything of a coarser nature, and allowed to pass only this pure element. When the light of day surrounds the stream of vision, then like falls upon like, and they coalesce, and one body is formed by natural affinity in the line of vision, wherever the light that falls from within meets with an external object. And the whole stream of vision, being similarly affected in virtue of similarity, diffuses the motions of what it touches or what touches it over the whole body, until they reach the soul, causing that perception which we call sight. But when night comes on and the external and kindred fire departs, then the stream of vision is cut off; for going forth to an unlike element it is changed and extinguished, being no longer of one nature with the surrounding atmosphere which is now deprived of fire: and so the eye no longer sees, and we feel disposed to sleep.” (Jowett translation)

It is not difficult to see the parallel between Jesus — about to be executed — and Socrates, as well as Peter, James, and John, and Socrates’ three friends. Socrates, like Jesus, is a tekton. Bar-Timaeus is blind, and Timaeus has a discussion of optics and the physics of the eye. Like Jesus, Socrates will enlighten his companions as to the truth. . . . .

I am looking forward to posting more on the ideal hero that Socrates represents, and how he is, strange as it sounds on the surface, an epitome of the heroic qualities of the great Homeric hero, Achilles. The same heroic qualities are also found in Jesus, but this is for another post.

Dennis MacDonald has proposed (The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark) the name and role as a blind prophet are inspired by Tiresias, the blind prophet in Homer’s Odyssey:

| Bartimaeus | Tiresias |

|

|

So far this is addressing only the name of the one healed at Jericho. More significant is the way the name is used, and how this pericope sits within the immediate structural and thematic context within the Gospel of Mark. That discussion brings out even more starkly the symbolic nature of this healing narrative. It will be seen that the story is not about healing a blind man. The healing of a carefully structured means of conveying a clear message about the identity of Jesus and the true nature of discipleship.

Time prevents completing this post so soon, though. The remainder will have to wait for another day.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“He could never have been called “Bartimaeus son of Timaeus” (=Bar Timaeus bar Timaeus!)”

At first, I would interpret this as “Bartimaeus, (that is) son of Timaeus”. I would assume that Mark is translating the Aramaic name into Greek. Why this interpretation is discarded?

This is what Richard Bauckham appears to argue. The reason Spong rejects it (and so do I) is that the construction “Name, son of so-and-so” normally means just that, that the Name is the son of so-and-so. When Mark is translating or explaining the meaning of an Aramaic phrase or word he says that is what he is doing. Thus:

Mark 5:41 “And he took the damsel by the hand, and said unto her, Talitha cumi; which is, being interpreted, Damsel, I say unto thee, arise.”

Mark 15:22 “And they bring him unto the place Golgotha, which is, being interpreted, The place of a skull.”

Mark 15:34 ” And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? which is, being interpreted, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

I also suspect there would be no need to interpret something as simple as Bar-Timaeus as a name for a Greek audience who would have been reasonably familiar with biblical and Aramaic names beginning with Bar/Ben. . .

““He could never have been called “Bartimaeus son of Timaeus” (=Bar Timaeus bar Timaeus!)”

At first, I would interpret this as “Bartimaeus, (that is) son of Timaeus”. I would assume that Mark is translating the Aramaic name into Greek. Why this interpretation is discarded?

Comment by IlCensore — 2011/02/08 @ 11:25 pm | Reply

*

This is what Richard Bauckham appears to argue. The reason Spong rejects it (and so do I) is that the construction “Name, son of so-and-so” normally means just that, that the Name is the son of so-and-so. When Mark is translating or explaining the meaning of an Aramaic phrase or word he says that is what he is doing. Thus:

Mark 5:41 “And he took the damsel by the hand, and said unto her, Talitha cumi; which is, being interpreted, Damsel, I say unto thee, arise.”

Mark 15:22 “And they bring him unto the place Golgotha, which is, being interpreted, The place of a skull.”

Mark 15:34 ” And at the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice, saying, Eloi, Eloi, lama sabachthani? which is, being interpreted, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

I also suspect there would be no need to interpret something as simple as Bar-Timaeus as a name for a Greek audience who would have been reasonably familiar with biblical and Aramaic names beginning with Bar/Ben.”

JW:

“Matthew” too apparently did not interpret “Mark” as interpreting “Bartimaeus” to mean “son of Timaeus”:

http://www.errancywiki.com/index.php?title=Matthew_20:30

“And behold, two blind men sitting by the way side, when they heard that Jesus was passing by, cried out, saying, Lord, have mercy on us, thou son of David. (ASV)”

“Matthew” apparently saw two names in “Mark” and this explains his unique two people here. In general, “Matthew” reduces “Mark’s” 1st century Israel errors and here may have also recognized that in Jewish Jericho it would be unlikely to be referred to as the son of your father’s Greek name. Yet again, support for Markan priority as we have a reason in “Mark” for “Matthew” to multiply the names but no corresponding reason in “Matthew” for “Mark” to reduce.

Wikipedia deserves credit here for presenting the figurative possibility:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Healing_the_blind_near_Jericho#Bartimaeus

“The naming of Bartimaeus is unusual in several respects: (a) the fact that a name is given at all, (b) the strange Semitic-Greek hybrid, with (c) an explicit translation “Son of Thimaeus.” Some scholars see this to confirm a reference to a historical person;[5] however, other scholars see a special significance of the story in the figurative reference to Plato’s Thimaeus who delivers Plato’s most important cosmological and theological treatise, involving sight as the foundation of knowledge. [6]”

In my now Legendary Thread at FRDB:

http://www.freeratio.org/showthread.php?t=202511&page=3

Mark’s DiualCritical Marks. Presentation Of Names As Evidence Of Fiction

I go to the trouble (and with apologies to Burridge) of presenting:

Wallack’s criteria for Figurative use of names:

1) Recognition through reading or sound.

2) Demonstrated style of the author.

3) Contextual fit.

4) Thematic fit.

5) Lack of known literal fit.

6) Fictional story.

“Bartimaeus” as figurative is also supported by the specific parallel “BarAbbas” which looks even more contrived.

So we have good reason to suspect that “Bartimaeus” is fiction. But where McGrath el-all are right is this is certainly not proven or probable because of the accursed source problem. No first-hand evidence that it was fiction. No second hand. No any hand.

Joseph

JW:

Kelber lays out the larger Contrived structure of “Mark” ending with the Batimaeus story in his classic “Mark’s Story of Jesus” starting on page 43. After Jesus’ identity is revealed in Chapter 8 the Mid-section of the story is characterized by the “On the Way” son of Mantra which “Mark” uses rePetedly here (while “Matthew”/”Luke” keep exorcising the phrase – as always, more evidence for Markan priority Neil). “On the Way” is the journey to Passion (Jerusalem). Kelber righteously points out that Jesus’ Mission on the Way is to make the Disciples “see” the Passion which of course “Mark’s” Jesus repeats, uh, um, let’s see, how many times? Help me out here Wilson. In “Mark’s” two-step dance, the first step is identify Jesus as the Messiah. The second step is to “see” what that means.

“Mark” FRAMES the entire journey here between two holy seeing stories. The blind man at Bethsaida (8.22) and blind Bartimaeus at 10:46. Note that 8:22 is immediately before Jesus is IDed and 10:46 is immediately before Jerusalem. Note the Style here of “Mark” where the framing technique is used for an entire section. The “seeing” of the blind followers is contrasted with the failure to see of the Disciples. This is a l – o – n – g W – a – y from historical witness. Subsequent Christianity wants to believe that historical witness evidenced Jesus making the Passion predictions, but the original narrative is saying something much less evidential, Jesus’ made Passion predictions (and not that historical witness said he did).

Bilezikian picks up the X-uh-Jesus son of Mantle on page 87 and explains the relationship of Bartimaeus to the critical Messianic secret. Bethsaidwhodat? is right before Jesus’ identity is revealed so the sight restoral operation is done in private and secrecy is commanded. Bartimaeus’ sight restoral (sight unseen) is given “On the Way”, after revealed identity, so this is highly public and there is no silence command. Bartimaeus follows Jesus…on the Way.

This mid-section journey is the link between the Teaching & Healing Ministry and the Passion (I think the author is painting a picture to some extent that the T & H Ministry is going around in circles). Little did the Christian god know that 2,000 years later, Jewish followers of the Pharisees and rejectors of Jesus would do more healing between Shabbats than Jesus did in an entire career.

The objective student should note than that “Mark” not only has Contrivance for individual stories but also has a significant dose of it at the larger structural levels. Another arrow in the MJ quiver. Something McGrath el-all has now been shown but can not see.

Joseph

Evidence for Markan priority? No, circular reasoning.

Bill, there’s nothing wrong with keeping an open mind to alternative possibilities. Theories of gospel relationships have been and will surely continue to be in flux and “consensus” positions will mark milestones in scholarship’s history as they have always done. What Mark’s treatment demonstrates is a clear independence of themes from the other gospels. It is very easy for many reasons to draw a trajectory line from Mark to the others. But there’s nothing wrong with keeping the back door open to other possibilities. Especially when we don’t know who wrote these things or when or for whom.

Neil, my comment was directed to Joseph’s “evidence” for Markan priority. It was not directed to your post.

Anyway, to respond to your comment: I see many common themes when comparing Matthew and Mark. Of course there are also a few different themes (they have slightly different interests of course), but “independence of themes” suggests to me that you are focusing on the differences and ignoring the similarities. I agree that it is possible to see a trajectory from Mark to Matthew, but I can also see a trajectory from a proto-Matthew to a Mark (this is something I hadn’t realized until recently – being influenced by the consensus view as we all are). These arguments are so often reversible and do not constitute evidence for literary dependence.

JW:

As always the source problem prevents any conclusion regarding priority not proven, probable or even likely and Neil’s related point that the different motivations of the Gospellers could move the story either Way is well received. Regarding “Mark’s” use of “on the Way” here as evidence of originality, the offending phrase fits the physical context (journey) and the figurative context (following Jesus) very well. Such a natural fit to both where the original author was emphasizing both together, suggests originality.

Regarding your follow-up use of “proto”, chink. This word is normally used by those whose conclusion is probably less likely.

In one of Jesus’ pre-baptism sayings, which regrettably did not go Canon, he explains the probabilities above:

Jesus: Okay, I have a pair of pants here, a 53 Medium. Now, no one would really know for sure, but who do they likely belong to?

Peter: Should I consider this a secret teaching or an open one?

Herod: John the Baptist?

Paul: They belong to Jesus. Not you but my spiritual one.

James McGrath: Since it would be embarrassing to lose your pants they probably belong to the historical Jesus.

Glenn Beck: Adolf Hitler.

Priest: My last appointment.

Jesus: They probably belong to whoever they fit best.

Joseph

A proto Gospel is nothing more than a realization that our text-critical reconstructions of the gospels do not get us back to the original texts.

I have slightly revised a portion of this post to bring out more the significance of Price’s (and others’) observing that the name in Aramaic relates to Bartimaeus’ role as a beggar. A bit like a Happy Families card game name: Mr Baker the bread-maker, etc.

I found this interesting:

http://christhum.wordpress.com/2009/10/26/the-name-fame-and-shame-of-bartimaeus/#more-326

What I haven’t seen yet (I probably missed it) is a discussion of טמא (defiled or unclean, hence outcast and hated) versus דוד (David, lit. “beloved”). The son of the beloved reaches out to the son of the hated. Bartimaeus is healed and becomes one with the throng that is marching toward Jerusalem.

Is this part of the Restoration of Israel theme?

Thank you for your carefully constructed analysis here. It seems like all these other comments have scratched out nothing but hyperbole of the most distracted order. JESUS – Son of David – is doing what only Jesus can do – taking the Son of Poverty, wretchedness, ” Spiritual Blindness” and sin – the one that others wished to silence and discard ( he wore a cloak – which was a symbol in his society of his “LOT in life” – he was a no good beggar). and restores his sight. Now Bartimaeus can see Jesus as he is. Would to God some of these commenters had the spiritual insight of Bartimaeus.