Following on here from my earlier post.

Following on here from my earlier post.

As noted in my previous post, Matthew and Luke inform us directly that the miracles of Jesus were for the purpose of identifying Jesus as the Messiah in accordance with the prophecies in Isaiah.

We may, if we wish, speculate that there really were a set of healings performed by charismatic, shaman-like person and that gospel authors completely re-imagined the way these occurred and subsumed those imaginative reconstructions beneath their primary interest of writing a narrative to demonstrate prophetic fulfilments of Isaiah, but that can never be anything more than idle speculation. We have no evidence for such historical antecedents so let’s work with the evidence we do have.

As the discussion following my previous post on this topic shows I have discussed this several times before with detailed analyses of certain miracles (particularly in Mark’s gospel) showing they were intended to be read not as literal events but as symbolic of theological messages. This post draws heavily on Bishop Spong’s perspective of the same argument as found in his Jesus For the Non-Religious. Of the passages in Luke and Matthew in which Jesus is quoted as telling the messengers of John the Baptist that the miracles are signs that he is the Messiah, Spong writes:

That is a strong argument, I believe, that these narratives should not be treated as literal events that actually happened, but as messianic signs attached to the story of Jesus to identify him with the messianic role of ushering in the kingdom of heaven. These are, therefore, interpretive narratives far more than they are descriptions of supernatural events. (p. 81)

I believe so, too. Some people object that arguing for a nonliteral interpretation is an entirely modern proclivity and it would seem to beggar belief that only now have people understood how the gospels should be read. Spong’s response to that objection is this:

The non-Jewish interpretation of the gospels [that is, a literal interpretation, reading them as narratives of literal events], during what I call the Gentile captivity of the church (which lasted from about 100 CE until relatively recently), did not understand these Jewish references. Only when Christianity in the last half of the twentieth century finally began to recover its Jewish perspective would these Jewish references be understood in their original context. Miracles say little about history. They say a great deal about the specific interpretive images that were applied to Jesus in order to understand what it was that people actually experienced in him. Once the modern twenty-first-century reader understands that, then they story opens in fascinating ways. (p. 81)

Reading Spong’s emphasis on the need to understand ancient Jewish ways of writing and interpreting narratives makes a strange contrast with reading the call (by scholars like Vermes, Sanders, Casey, Crossley, and many others) for understanding Jewish customs in order to interpret the narrative accounts as if they are literal history.

The miracles in the Gospel of Mark

Then the eyes of the blind shall be opened (Isaiah 35:5):

And the ears of the deaf shall be unstopped . . . And the tongue of the dumb sing (Isaiah 25:5, 6)

Then the lame shall leap like a deer (Isaiah 35:6)

To proclaim liberty to the captives, to open the prison to those who are bound (Isaiah 61:1)

- Exorcising the demon in the synagogue

- Excorcising Legion

- The Syro-Phoenician’s daughter

- Exorcising the deaf and mute spirit

To restore to wholeness

There is also the raising of the dead, and this sits with the belief that the time of the Messiah would also be the time of the resurrection of the dead. (Not discussed by Spong, but also worth noting, is the popular belief that Solomon was an exorcist.)

A close analysis of these stories, however, reveals something even more than just supernatural healing. The narratives are filled with hidden messages and code language. (p. 81, my emphasis)

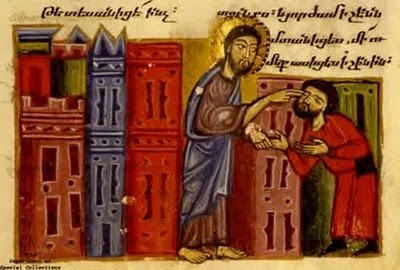

The two-stage healing of the blind man from Bethsaida

Then He came to Bethsaida; and they brought a blind man to Him, and begged Him to touch him.

So He took the blind man by the hand and led him out of the town. And when He had spit on his eyes and put His hands on him, He asked him if he saw anything.

And he looked up and said, “I see men like trees, walking.”

Then He put His hands on his eyes again and made him look intently [“intently”: Spong uses “intently” rather than up: see the Greek word linked here] and he was restored and saw everyone clearly. Then He sent him away to his house, saying, “Neither go into the town, nor tell anyone in the town.”

Spong points to the significance of the passage in Mark that follows directly on from this two-stage healing the blind man of Bethsaida (8:27-33):

27 Now Jesus and His disciples went out to the towns of Caesarea Philippi; and on the road He asked His disciples, saying to them, “Who do men say that I am?”

28 So they answered, “John the Baptist; but some say, Elijah; and others, one of the prophets.”

29 He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?”

Peter answered and said to Him, “You are the Christ.”

30 Then He strictly warned them that they should tell no one about Him.

31 And He began to teach them that the Son of Man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again. 32 He spoke this word plainly. [compare the man seeing clearly]

Then Peter took Him aside and began to rebuke Him. 33 But when He had turned around and looked at His disciples, He rebuked Peter, saying, “Get behind Me, Satan! For you are not mindful of the things of God, but the things of men.”

Spong declares, “This is obviously not history.”

The precise prediction of the suffering, the crucifixion and the resurrection is a clear reading back into the historical life of Jesus the story of the climactic final events.

One might also add here that it was a common feature of ancient novels, epics and drama for plots to be driven by prophetic announcements. The audience was regularly informed what to expect through such prophecies. The drama was in seeing how they worked out in detail.

It is not history. But it is a coded narrative.

Peter is portrayed as one who presumed he understood, but whose subsequent words reveal that he did not. His “seeing” came by stages, Mark was saying. When we add to this detail the fact that we know from John’s gospel that Peter came from Bethsaida (John 1:44) and that the giving of sight to the blind man from Bethsaida was said to have occurred in stages, with the final seeing accomplished only when Jesus and the blind man stare “intently” at each other, it begins to sound more like a parable of the life of Peter.

When we next read the story of Peter’s denial, we see the details of his lack of understanding at Caesarea Philippi. Luke seems to be referring to Mark’s narrative about this blind man very specifically when, in his story about Peter’s denial, he states, “The Lord turned and looked at Peter” (Luke 22:61). That intense stare, which gave the blind man from Bethsaida his full sight, in Luke’s story causes to Peter to remember and to weep bitterly. (p. 82 f.)

I have tended to see Mark’s focus more on the twelve collectively, with Peter as the representative of them all, rather than specifically on Peter as Spong describes here. (I do find the Bethsaida association with both Peter and this blind man interesting, though. It does mean House of the Fisher, after all, and Peter was a fisherman. Nonetheless, I don’t know that we need to see this geographical metaphor (yes, Mark’s place names, I believe, are chosen as metaphors) as a pointer exclusively to Peter. There were four fishermen called to be the leading disciples. Peter remains their representative, but they were all called to be fishers of men.

The passage following the two-stage healing is important. It does, as Spong observes, contain the conceptual links of two types of seeing who Jesus is, and of Jesus revealing the full meaning of his identity plainly, etc. But the preceding chapters leading up to the healing at Bethsaida are also instructive.

Jesus attempted to instruct the disciples through the miraculous feeding of the crowd of 5000 (Mark 6:34-44). Immediately after sending the crowds away after this miracle, Jesus ordered his twelve disciples to sail without him to Bethsaida. They left while Jesus went up to a mountain to pray.

Incidentally, these sorts of geographical and time matrixes just don’t work for me as realistic settings. Going up a mountain to pray and sending away a crowd of 5000 people just doesn’t happen in twenty minutes. Yet a little thought about all the events being described in this section leads us to imagine some quite fanciful movements. This is where I think familiarity, not to mention artistic verisimilitude, has misled Michael Vines into describing Mark’s time and geographic settings as realistic. They are not. They are as artificial as the character and place names themselves. The Gospel is much closer to the genre of Jewish novel than even he realizes.

Jesus next appears walking on the sea as the disciples struggle against a strong head-wind late at night. The disciples scream in terror thinking they are seeing a ghost. That’s real blindness to Jesus’ identity for you. Or maybe it’s half-blindness, like seeing men looking like trees.

So Jesus does the whole thing all over again (Mark 8:1-10), only this time with a crowd of 4000. (I realize there is much more to these passages than the simple teaching of the disciples, but this is the theme I’m addressing now.) This is not, as some commentators have said, the work of a clumsy redactor sticking a second version of the same miracle story almost right beside the first. It is one of Mark’s several intentional doublets. He even tells his readers that what they are about to read is indeed something that is happening “again”, and subsequently has Jesus speak of the two miracles in a single lesson he is attempting to impart to the disciples (8:17-21).

17. But Jesus . . . said to them, “Why do you reason because you have no bread? Do you not yet perceive nor understand? Is your heart still hardened? 18 Having eyes, do you not see? And having ears, do you not hear? And do you not remember? 19 When I broke the five loaves for the five thousand, how many baskets full of fragments did you take up?”

They said to Him, “Twelve.”

20 “Also, when I broke the seven for the four thousand, how many large baskets full of fragments did you take up?”

And they said, “Seven.”

21 So He said to them, “How is it you do not understand?”

The disciples have been given the same lesson twice but still do not understand. Then follows the two-stage healing of the man from Bethsaida.

Even when Peter is told plainly what Jesus is, and what it means to be the Christ, Peter reacts as if blinded by the light. There is none so blind as those who will not see. The demons recognized Jesus, and Peter’s “recognition”, Jesus says, leaves him no better off than Satan.

The placing of this two-stage healing of this blind man between the dual lessons of the mass feeding miracles and the recognition scene at Caesarea Philippi is neither accidental nor historical. It is drenched with symbolism. Christ must raise his eyes in despair over scholars who fail to see, like the disciples, beyond the literal.

This is long enough for one post. Had originally intended to complete Spong’s discussion here but I always end up taking longer than I ever anticipate before I ever finish one of these things. Will complete in a future post.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Mark’s telling of the two-stage healing of the blind man from Bethsaida strikes us as odd first because Jesus spits either “on” the man’s eyelids or “into” his eyes and second because the healing apparently needed some follow-up fine tuning. However, even more oddness lies just beneath the surface.

Verse 8:23 contains three words that Mark uses only once: ἐπιλαβόμενος (grasping), ἐξήνεγκεν (he brought/he carried out), and ὄμματα (eyes). The most unusual word in this trio is ὄμματα (ommata), a poetic word that Plato, for example, uses when describing the “eye of the soul.”

Curiously, this word appears only one other time in the New Testament. When Matthew retells the story of Blind Bartimaeus, he drops the name and changes him into a blind duo (perhaps leading each other into the ditch?). While Mark and Luke say that Bart asked, “…let me receive my sight,” Matthew says the two men ask to have their “eyes (ὀφθαλμοὶ) opened.” And so Jesus touches their eyes (ὀμμάτων), they receive sight, and they follow him.

We’re told that Matthew and Luke dropped the story of the story of the blind man healed by spit, but I think Matthew plucked him from Bethsaida and moved him next to Bartimaeus, smashing the stories into one (editing out the holy saliva and walking trees). This explains Matthew’s use of the poetic ommaton.

By the way, ἐξήνεγκεν [exenegken] is the verb sometimes used to describe carrying corpses out of the city, as in Acts 5:6,10. Is the receiving of sight to the eye of the soul a kind of resurrection?

In thinking about the possibility of regaining eyesight representing a resurrection it is worth comparing the resurrection of Jairus’s daughter. Jairus, as we know, means Enlightened or Awakened, and there death is likened to a sleep and resurrection to being awakened.

If we dwell on these sorts of possibilities we might find ourselves wandering dangerously afar from orthodoxy, however. Wasn’t it supposed to have been the gnostic types who equated salvation (resurrection) with insight, revelation, knowledge (that is, enlightenment)?

If I understand Margaret Barker correctly, it isn’t a deviation from from the orthodox position; it’s the original thing.

“In temple theology, resurrection was not a post mortem experience. It was a theosis, the transformation of a human being into a divine being — which came with the gift of Wisdom..” (emphasis hers) Temple Theology, p. 23

Mystery, blindness, sight, understanding, enlightenment, wisdom, theosis, resurrection. There’s a whole lot more here than meets the eye (ὀμμάτων?).

No doubt. I meant it is us who would be wandering from the “orthodox” line of interpretation. I have been looking at April DeConick’s work on mysticism, which looks at how visionary experiences were salvation experiences. To see the God was to “become” one with the god/dess. It containts the same sorts of ideas as I read about the Eleusinian mysteries by Kerenyi.

“Another” second Temple messianic Jewish sect was influenced by these kinds of OT verses -the writers of the Dead Sea Scrolls. 4Q521 also speaks of a messiah who will “release the captives, make the blind see, raise up the do[wntrodden]” and “heal the sick, resurrect the dead, and to the Meek announce glad tidings” (The Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered pg. 23; cf. Mt. 11:5, LK 4:18, 7:22). Vermes has a similar translation.

Yet at the same time the miracles in the NT have clear parallels in pagan culture, even in what must have been contempory literature, like the miracles of Vesapasian mentioned in Tacitus. The Christ myth is a clever synthesis of Jewish and pagan cultures created by people with the aim of winning the greater war of panhellenism vs. messianic Judaism. The OT was just another tool in their belt.

I know there is more coming from you, but this study seems to be about the fact that they did use this tool and the hows and whys of it. But that alone won’t explain who they are, in my opinion. These weren’t messianic Jews so much as people simulaneously infuenced and threatened by messianic Judaism. And I think that the people at History Hunters International have their number.

Agree that the gospel narratives drew upon a wider range of material than was offering in the Jewish market. I once compared the various resurrection appearances in non-Jewish literature with what we find in the gospels and the similarities there are undeniable.

What is the view of the History Hunters International?

A quick glance at this article will tell you more than I can in the same amount of time.

//historyhuntersinternational.org/2010/06/05/chrestians-and-the-lost-history-for-classical-antiquity/#

I’ve been following this website for about a year now. They are one of the few ancient historians that take Eisenman seriously when it comes to who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, and in my opinion they also ably pick up the baton of the question of who created the Christ myth.

Hi, the History Hunters link now redirects to a spam site.

Looks like that one is dead and gone. Not even stored in the “wayback machine“.

Excellent series of posts–though the situation in the gospels is IMO a bit more complicated. What’s really going on is, the original layer of miracles was indeed wholly symbolic. It was later redactors, editors, compilers, and authors who turned Jesus’ healings into “magic-man” miracles (probably to compete with the reputations of other holy men who claimed to achieve such healings). I hope to post on this subject in my blog at some point in the near future. It’s an extremely interesting topic.

For what it’s worth I had posted a year or two ago a comparison of the ways Mark and Matthew treat the same miracle. Matthew does like to create a bit of drama and sensationalism while Mark is sticking to the symbolic regardless of aesthetics.

JW:

Great stuff Neil:

http://www.errancywiki.com/index.php?title=Mark_8

“Mark 8:22 And they come unto Bethsaida. And they bring to him a blind man, and beseech him to touch him.

8:23 And he took hold of the blind man by the hand, and brought him out of the village; and when he had spit on his eyes, and laid his hands upon him, he asked him, Seest thou aught?

8:24 And he looked up, and said, I see men; for I behold [them] as trees, walking.

8:25 Then again he laid his hands upon his eyes; and he looked stedfastly, and was restored, and saw all things clearly.

8:26 And he sent him away to his home, saying, Do not even enter into the village.

8:27 And Jesus went forth, and his disciples, into the villages of Caesarea Philippi: and on the way he asked his disciples, saying unto them, Who do men say that I am?

8:28 And they told him, saying, John the Baptist; and others, Elijah; but others, One of the prophets.

8:29 And he asked them, But who say ye that I am? Peter answereth and saith unto him, Thou art the Christ.

8:30 And he charged them that they should tell no man of him.

8:31 And he began to teach them, that the Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders, and the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again.

8:32 And he spake the saying openly. And Peter took him, and began to rebuke him.

8:33 But he turning about, and seeing his disciples, rebuked Peter, and saith, Get thee behind me, Satan; for thou mindest not the things of God, but the things of men.”

As usual the Thematic source here is Paul. Paul’s two-step Themology is:

1) Jesus was the Jewish Messiah

2) Jesus’ fulfillment of Messiah was not what you expected

In the related Markan stories here, “Mark” has the same two-step process:

1) IDENTIFY Jesus as the Messiah

2) Understand WHAT that means (It’s not what you/Peter/Disciples/Crowds/Priests/Scribes/Romans expected)

In general the anonymous seekers in “Mark” are contrasted with the Disciples and especially Peter. The anonymous meet Jesus’ pre-determined formulas for successful follower behavior in contrast with the Disciples and especially Peter who meet Jesus’ pre-determined formulas for follower failure, often a mere chapter after given.

In the context of the two-step program, the man who still can not see properly, UNDERSTANDS what he is seeing:

“And he looked up, and said, I see men; for I behold [them] as trees, walking.”

Literally, he can not see the men, but he understands that they are men (understand dear Reader?).

This is than (as usual) contrasted with Peter. He sees clearly that Jesus is the Messiah but when Jesus explains clearly what that means:

“And he spake the saying openly.”

Peter does not “understand”. Actually “Mark” makes clear here that “not understand” is figurative for “not accept” as Peter gets all emotional here.

As a side note, note the strong element of Greek Tragedy here with Recognition based on identity creating the pivot of Reversal of fortunes exactly half the Way through.

Joseph

Query: Not denying it, but what passages in Paul lead you to understand that Paul thought of Jesus as a Messiah who reversed expectations of Messiahship?